Election of species requirements are part of U.S. patent restriction practice. Examiners often caption these matters an “election/restriction” or the like. Election requirements deal with how genus and species inventions are disclosed and claimed. This differs from regular restriction practice, which requires an applicant to elect one group of claims from among different groups of claims to independent or distinct inventions identified by an examiner. Instead, an election requirement deals with an application in which there is a generic (genus) invention claimed as well as more than one species of invention within that genus claimed. In this sense, an election requirement is a special type of restriction. It is possible to have both types of restrictions, by groups of claims and by species, issued at the same time.

The Basics of an Election Requirement

More than one species of an invention, “not to exceed a reasonable number,” may be specifically claimed in different claims in a single U.S. patent application, provided that the application includes (i) an allowable claim generic to all the claimed species and (ii) all the claims to species in excess of one are written in dependent form or otherwise include all the limitations of the generic claim. But where two or more species are claimed, a requirement for restriction to a single species may be proper if the species are mutually exclusive.

A species restriction acts as a kind of cap on the amount of searching that a U.S. patent examiner has to do for a given application, limiting it to a reasonable number of species. It is possible for applicants to include dozens or even hundreds disclosed species embodiments in a single application. Genus/species election practice helps prevent examiners from being overwhelmed by the presence of voluminous numbers of species. Election requirements may arise where the examiner suspects that the generic claim will not be patentable/allowable but the number of disclosed species makes searching them all impractical.

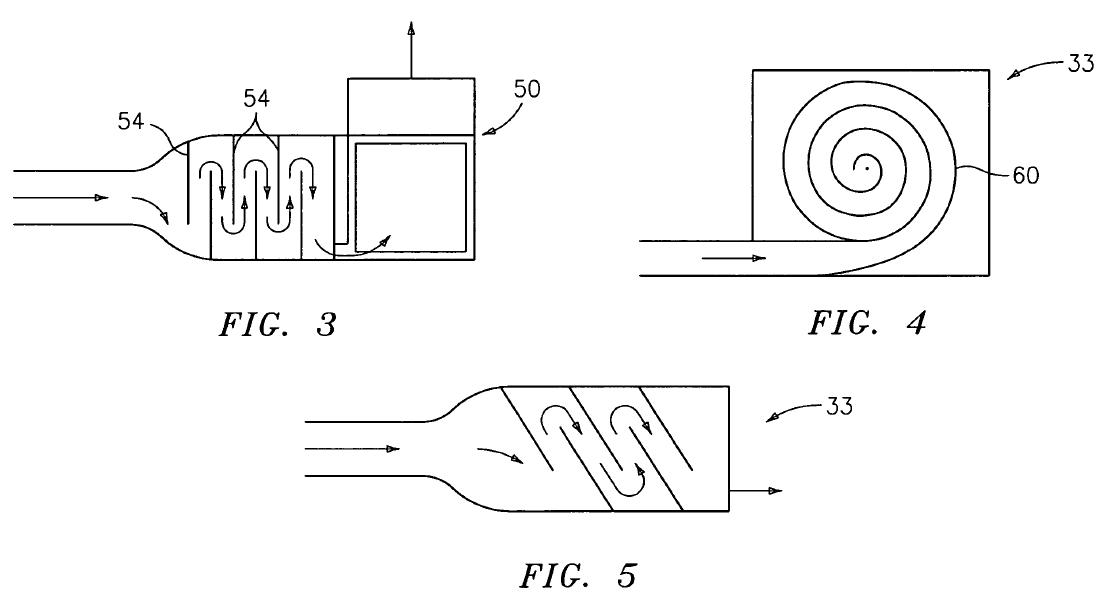

A key aspect of election requirements is that they are based on an examiner identifying different disclosures—often by figure, but sometimes with reference to the detailed description of the specification. In reply, the applicant then has to elect one species and identify the claims that read on that elected species and those that are generic. Perhaps the most important point about elections of species is that the claims will be restricted to the elected species if no claim to the genus is found to be allowable. So, really, an election requirement is the examiner saying (contingently) that if there is ultimately no allowable generic claim, then there will be claims to independent and distinct inventions (species) and a serious examination burden will be present. This ties the election of disclosed species to a restriction between claims in the application.

Election requirements can arise in just about any patent application. However, election requirements are somewhat more common for chemical, biotech, and similar types of inventions. Election of species requires are a creation of USPTO regulations and are not explicitly provided for in statutory law, other than in relation to regular (statutory) restriction practice.

What is a “Species”?

Species always refer to the different embodiments of a generic (or genus) invention. In contrast, claims are definitions or descriptions of inventions. Claims themselves are never species as such. The scope of a given claim may be limited to a single disclosed embodiment (i.e., a single species, and thus be designated a specific species claim). Alternatively, a given claim may encompass two or more of the disclosed embodiments (and thus be designated a generic or genus claim). Species may be either independent or related as disclosed in a given application.

As an example, consider a mechanical invention with a first part connected to a second part. In one species embodiment, they are connected by a mechanical fastener (e.g., bolt, screw, rivet, etc.). In another species embodiment, they are connected via an applied electromagnetic field. In yet another species embodiment, they are connected via a chemical reaction that occurs between the parts when treated in a chemical bath. These embodiments might be claimed in a mutually exclusive way, and searching one may not capture prior art relevant to the others. Although the there may be a generic invention to the first and second parts being connected, regardless of how they are connected.

What is “Generic” or a “Genus”?

Initially, it is important to distinguish between generic or genus inventions as disclosed, on one hand, and generic claims, on the other. Election of species practice begins with identification of disclosed species. However, generic disclosures do not matter much for election requirements and replies. Rather, election practice only really cares about generic claims, in relation to specific species claims.

What constitutes a generic claim depends upon the specific species claims that are present in a given application. The USPTO says that, in general, a generic claim should require no material element in addition to those required by the specific species claims, and each of the specific species claims must require all the limitations of the generic claim. If you have claims that are mutually exclusive, and there are material elements recited in one claim but not another, there may not be a generic claim and instead there may simply be independent or distinct claimed inventions—in other words something subject to conventional restriction practice.

PCT National Phase Entry Applications

Regular election/restriction practice does not apply to PCT national phase entry applications. Instead, a unity of invention standard governs, which requires having a common or corresponding special technical feature that defines a contribution over the prior art. However, U.S. examiners can still issue requirements to elect a particular species in national phase applications and to withdraw non-generic claims to unelected species, and the procedures are ultimately similar. Applicants must still make elections and rejoinder of withdrawn claims is still possible. This means that the ultimate effects are similar though the terminology differs somewhat. If anything, there is slightly greater leeway for applicants to amend the claims to keep them together under the unity of invention standard.

If a U.S. examiner applies conventional election/restriction practice requirements to PCT national phase entry applications, that is a procedural error that should be called to the examiner’s attention. That sort of mistake does happen from time to time.

Keep in mind that prior indications by the international search authority or international preliminary examining authority in the international phase of a PCT application are not binding in the national phase. That means that even if a prior PCT written opinion indicated that claims posses unity of invention, the U.S. examiner could disagree and still issue a unity of invention election of species restriction in the national phase.

Requirements for an Election of Species Response

Patent applicants are required to elect a species for examination in reply to an election requirement and to identify the claim(s) that read on the elected species, as well as any generic claim(s). A reply (or response) is considered incomplete if no election of a particular species is made.

To the extent that a restriction between groups of claims to independent or distinct claimed inventions was also made, that election by claim group needs to be made in addition to the species election. Those different elections effectively stack on top of each other. The only claims that will be examined are those that are part of both the elected species requirement and the elected group of claims. In other words, the claims that will be examined will only be those that are the net result of the two elections (by claim group and by species).

An election of species can be either “with traverse” or “without traverse”. “Traverse” means that the applicant is arguing that the restriction requirement is incorrect or improper and should be reconsidered and withdrawn in whole or part. Traversing a species election/restriction requirement requires actually making an argument about why the species restriction is wrong. An election that is made subject to a traversal is called a provisional election. Traversing the election requirement is necessary to later file a petition to challenge it. However, it is highly uncommon to traverse an election of species requirement.

The applicant can also make an assertion about which claim(s) are generic that may differ from the examiner’s indication of the generic claim(s). This is often an critical aspect of responding to the election requirement.

Strategic Considerations for Election Requirement Responses

There are a few strategic considerations the go into deciding how to reply to an election of species requirement. Consider the following, for example:

- What is the most commercially important embodiment of the invention, or which embodiment has the most commercial potential? Many times this is the most important consideration.

- What generic claims are present? An examiner will generally indicate which claim(s) he or she thinks are currently generic. Applicants might not agree, and might indicate that additional or different claims are generic to all claimed species. Indications of generic claims, as well as indications of which specific species claims read on the elected species, can have significant impacts on later enforcement of any resultant patent. Such indications, or a failure to argue that certain claims are generic, may play a significant role in claim construction and the ability of competitors to avoid or design-around granted claims. These indications may also impact the scope and availability of the doctrine of equivalents.

- Which embodiment is covered by the most claims? All else being equal, sometimes an applicant might make an election simply to retain the largest number of claims.

- How does the election of species requirement relate to an accompanying restriction by groups of claims? Examiners will often issue both a restriction by identified groups of claims, and also require election of a disclosed species. Because only the claims that are encompassed by both elections will be examined, this sometimes favors making certain elections that will retain a reasonable number of claims.

- Might claims be amended? One or more claims might be amended in order to make them generic, to depend from a generic claim, and/or to make provide a linking claim. Claim amendments might be used to try to facilitate later rejoinder of claims directed to an unelected species.

- Are you willing to file one or more divisional application(s) to pursue unelected claims? A election/restriction requirement is an indication that filing unelected claims in a new divisional application will prohibit a double patenting rejection in the later-filed divisional. However, whether or not the applicant is willing to incur further expense associated with a divisional filing (or perhaps multiple divisionals) may influence which species is elected in response to the restriction. It is possible to defer a divisional filing decision so long as the current application remains pending. This may allow an opportunity for claim rejoinder to be considered. Ensure that there is a clear demarcation between restricted species and claims to preserve divisional filing safe harbor protections against double patenting. Keep in mind both short-term (e.g., costs to traverse and/or petition a restriction) and long-term costs (e.g., divisional filing and maintenance fees) associated with each option.

- Which species have the best chance of patentability? This may not be known. But, depending on the scope of the prior art or potential patent-eligibility issues, certain disclosed embodiments and corresponding specific species claims might face either easier or more difficult examinations. Sometimes an applicant has a sense of which claimed embodiment(s) are the most unique.

- Is it important to obtain a patent very quickly, or not? Certain elections of species may make examination take longer, such as if the election results in reassignment of the application to a different examiner in a different group art unit. Although the effect on the speed of examination may be speculative at the time of the species election.

When strategizing how to respond to an election of species requirement, the main issues are usually which species to elect and which claims to designate as being elected species-specific claims or generic.

It is often not advisable to challenge an election of species requirement by traversing it. Doing so usually involves admitting that the species are not patentably distinct, that is, that they are obvious variations of each other. That may limit the sorts of arguments that can be made later on to distinguish prior art, etc. Of course, there are situations in which examiners identify species incorrectly (e.g., incorrectly identifying different views of a single embodiment as different species), in which case traversal may be appropriate and worthwhile. Traversal is necessary to preserve the right to later petition against the restriction, however.

An experienced patent attorney can help an applicant assess possible election requirement response strategies for any given case.

Petitions Against Election Requirements

It is possible to file a petition against a election/restriction requirement that has been made final. Such petitions are decided by technology center directors, as opposed to the Office of Petitions or some other centralized USPTO authority. However, such petitions may not be worth the effort and cost in attorney fees–unless, for instance, the applicant faces a need for multiple divisional applications with a large total cost. Importantly, such a petition against an election requirement may be deferred until after final action on or allowance of claims to the invention elected, but must be filed no later than an appeal.

In order to preserve the ability to file a petition against an election requirement, it is necessary to traverse the election requirement in the initial response. Failing to traverse a restriction waives the opportunity to later file a petition against the election/restriction requirement.

Rejoinder

Unelected, withdrawn claims can potentially be rejoined upon the allowance of an elected claim. Claims that depend from or otherwise require all the limitations of an allowable claim are eligible for rejoinder. If a generic claim is allowed, then the election requirement effectively disappears and all claims are rejoined by default. Rejoinder is also possible when there is a “linking claim”. Rejoinder practice means that unelected claims might still have a chance to be included in a granted patent despite a prior restriction.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.