Under U.S. patent law, a distinction between analogous versus non-analogous art sometimes arises. Understanding when this concept matters, and how to draw a line between these two possibilities may be important. The following article explains what analogous and non-analogous art is, why it matters, and how to determine whether a given piece of prior art is analogous art or not.

I handled a patent application years ago related to fishing lures. The examiner had cited a prior art patent directed to a rocket fuel additive for a rejection in an office action. This fishing lure application was not rocket science, as the saying goes. But could the examiner properly say that a fishing-related invention was obvious because of a prior teaching about rocket fuel additives? The concept of non-analogous art helps to answer that question.

When Non-Analogous Art Status Matters

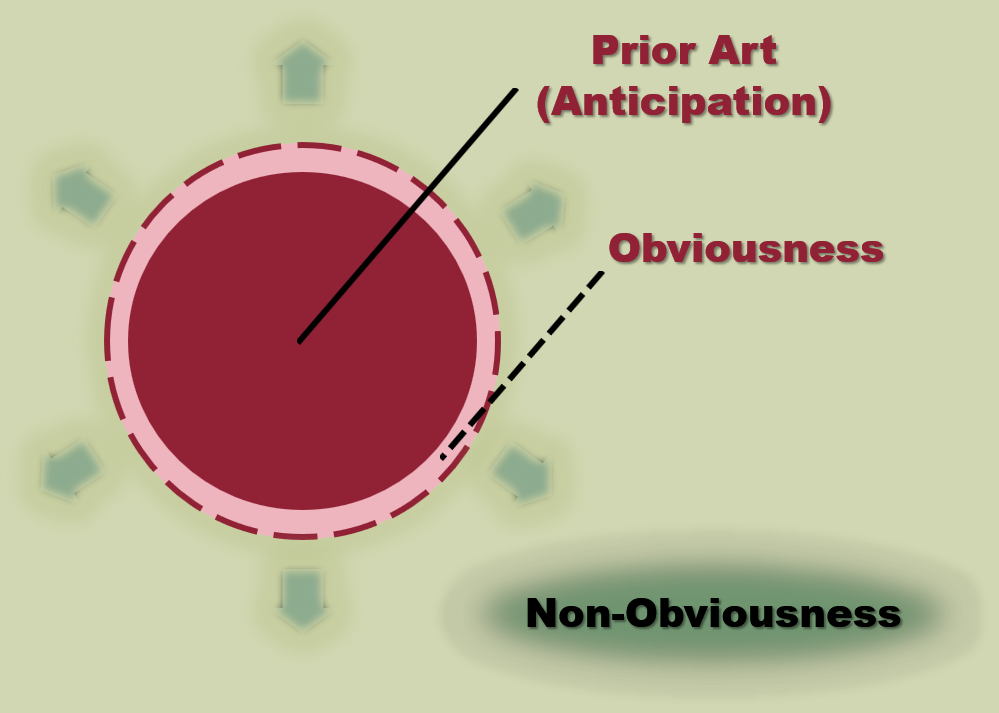

In order for a prior art reference to be usable to establish obviousness, the reference must be analogous art to the claimed invention. In re Bigio, 381 F.3d 1320, 1325 (Fed. Cir. 2004). Teachings in non-analogous art cannot be relied upon to establish obviousness. However, there is no analogous art requirement for a prior art reference being applied for anticipation. In re Schreiber, 128 F.3d 1473, 1478 (Fed. Cir. 1997).

There are two different ways to establish something is analogous art. Satisfying either one of them is sufficient. Under these tests or prongs, a prior art reference is analogous art to a claimed invention under either of the following circumstances:

- the reference is from the same field of endeavor as the claimed invention (even if it addresses a different problem); or

- the reference is reasonably pertinent to the problem faced by the inventor (even if it is not in the same field of endeavor as the claimed invention)

In re Clay, 966 F.2d 656, 658-59 (Fed. Cir. 1992).

Although, the evidence and analysis relating to the field of endeavor and reasonably pertinent prongs may overlap. And some prior art might satisfy both tests, even though the requirement is only that it satisfy one of them. However, the analysis for design patents might differ somewhat for the second prong/test.

A Burden To Meet When Disputed

The analogous art requirement is about the factual foundation needed to be able to rely on a given prior art reference for an obviousness argument. See In re GPAC, Inc., 57 F.3d 1573, 1577 (Fed. Cir. 1995); In re ICON Health & Fitness, Inc., 496 F.3d 1374, 1378 (Fed. Cir. 2007). This is not merely about what a given prior art reference literally teaches. It is about whether a person of ordinary skill would have been motivated to look at or otherwise consider a reference at all in relation to the claimed invention at the time of invention (or effective filing date). That makes this a kind of threshold that disallows obviousness arguments premised on obscure, remote, or out-of-context teachings.

This is also an aspect of the well-established notion that an obviousness analysis must not succumb to hindsight bias. Netflix, Inc. v. DivX, LLC, 80 F.4th 1352, 1358-59 (Fed. Cir. 2023). Jorge Luis Borges wrote in “Kafka y sus precursores” [Kafka and His Precursors]” (La Nación, August 15, 1951) that a writer modifies our conception of the past to create precursors. After describing various prior works with elements that resemble Kafka’s later work, he said, “Kafka’s idiosyncracy is present in each of these writings, to a greater or lesser degree, but if Kafka had not written, we would not perceive it; that is to say, it would not exist.” This is not a bad way of thinking about non-analogous art that only appears as a relevant precursor in hindsight. While Borges refers to writers generally, what he really was referring to was Kafka’s new and unique genius rather than ordinary writing that might merely reuse commonplace ideas and styles. This is like talking about inventive genius with patenting.

In the end, establishing that a reference is analogous art is a factual, evidentiary burden that a patent examiner or challenger must satisfy as part of arguing that a claim is unpatentable or invalid as obvious. Although, normally, analogous art status is assumed unless the patentee or applicant asserts that a given reference is non-analogous art. That means this question is not routinely addressed. In practice, it only arises when a patentee or applicant believes that an obviousness argument is improper. So, it is up to the patentee/applicant to raise this issue when applicable. Then the examiner or challenger must be able to show that the reference relied upon is analogous. That involves pointing to evidence that satisfies at least one of the two tests.

Intrinsic evidence, contained in the patent/application and its prosecution history, is generally the best and most significant. It is helpful to look at what is said in the claims, the title, and the background section, for instance, where identifications of technical fields and discussions of problems to be solved are frequently found. Often, this type of evidence alone is sufficient to determine if a reference is analogous or non-analogous art. But extrinsic evidence can also be used. For instance, there might be expert testimony in court about the knowledge and skill of a person of ordinary skill in the art, or reliance on additional patents or publications that indicate the knowledge and skill that prevailed in the art.

The Same Field of Endeavor Test

The field of endeavor test or prong asks whether the art is from the same field of endeavor as the claimed invention, regardless of the problem addressed. Bigio, 381 F.3d at 1325. This test rests on an assessment of the nature of the patent or application and claimed invention in addition to the level of ordinary skill in the art. Bigio, 381 F.3d at 1326.

The field of endeavor is determined by reference to explanations of the invention’s subject matter in the patent or application. This includes the function and structure of the claimed invention, taking into account the complete factual description of all embodiments. So this involves considering similarities and differences in structure and function between the claimed invention and the cited art. The field of endeavor is not limited to the specific point of novelty, the narrowest possible conception of the field, or to a particular focus within a given field. Courts tend to take an expansive view of the relevant field of endeavor. Netflix, 80 F.4th at 1359.

In the Bigio case, it was found that toothbrush art was analogous to a claimed hair brush invention. In support of that conclusion, the structure and function of the claimed hair brush invention was found to be similar to that of toothbrushes. Both were in the field of hand-held brushes having a handle segment and a bristle substrate segment. Also, it was found that toothbrush prior art could easily be used for brushing hair (e.g., human facial hair) in view of the size of the bristle segment and arrangement of the bristle bundles described in the reference.

Disputes over the proper application of this test are not particularly common, because it is often clear when a reference is or is not from the same field. But when disputes do arise, they tend to center around how broadly or narrowly the relevant field of endeavor should be defined. Patentees and patent applicants will tend to argue for a narrower definition of the field, which tends to exclude more potential prior art. Challengers and examiners may instead argue that the relevant field of endeavor is broad and generic. The correct approach in any particular case is the one best supported by the facts and evidence. In other words, this test requires both accurate identification of and careful review of the relevant facts.

The Reasonably Pertinent Test

The reasonably pertinent test or prong asks whether the reference still is reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved, even if the reference is not within the same field of endeavor. Bigio, 381 F.3d at 1325. Sometimes this is discussed in terms of a “purpose” instead of a “problem”, but this means the same thing.

When addressing whether a reference is analogous or non-analogous art to a claimed invention under a reasonable-pertinence theory, the problems to which the claimed invention and reference at issue relate must be identified and compared from the perspective of a person having ordinary skill in the art. The relevant question is whether a person of ordinary skill would reasonably have consulted the reference in solving a relevant problem. Although the dividing line between reasonable pertinence and less-than-reasonable pertinence is context dependent, it ultimately rests on the extent to which the reference and the claimed invention relate to a similar problem or purpose. Donner Tech., LLC v. Pro Stage Gear, LLC, 979 F.3d 1353, 1359-61 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

A reference can be analogous art with respect to a patent even if there are significant differences. Familiar items may have obvious uses beyond their primary purposes. And, for instance, a person of ordinary skill might reasonably consult a reference even if she would not understand every last detail of it, so long as she would understand the portions relevant to solving her problem well enough to glean useful information. Yet the pertinence of the reference as a source of solution to the inventor’s problem must be recognizable with the foresight of a person of ordinary skill, not with the hindsight of the inventor’s successful achievement. Sci. Plastic Prods., Inc. v. Biotage AB, 766 F.3d 1355, 1359 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

Also, the articulation of the purpose of or problem to be solved by the patent cannot be so intertwined with the field of endeavor as to effectively exclude consideration of any references outside that field. The second prong cannot be collapsed into the first. It must remain a distinctly additional way of establishing analogousness. Donner, 979 F.3d at 1360. And, further, the so-called teaching, suggestion, or motivation (TSM) test for obviousness was overturned by the Supreme Court in KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007). That means overly strict problem statements cannot be used to limit obviousness to express suggestions to combine references or to otherwise ignore or contradict the background knowledge possessed by a person having ordinary skill in the art. Airbus SAS v. Firepass Corp., 941 F.3d 1374, 1383-84 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

The Airbus case involved a patent that claimed “A system for providing breathable fire-preventive and fire suppressive atmosphere in enclosed human-occupied spaces” and addressed the problem of fire prevention and fire suppression. The cited reference that the patentee alleged was non-analogous was a prior patent by the same inventor that disclosed equipment for providing hypoxic air in an enclosed area for the purposes of athletic training or therapy. Four additional prior art references (that is, other extrinsic evidence beyond the cited reference alleged to be non-analogous) established that use of normbaric hypoxic atmospheres in enclosed environments was well-known in the art of fire prevention and suppression at the time of the invention. The court found that an ordinarily skilled artisan seeking to address the problem identified by the patent in question would reasonably have consulted the cited reference relating to enclosed hypoxic environments because it was reasonably pertinent to a similar problem, even though it was from a different field of endeavor. The court therefor overturned a prior decision refusing to consider the extrinsic evidence about knowledge that was available in the art, which linked the challenged claim and the cited prior art reference by a common technical problem.

In re Klein, 647 F.3d 1343, 1350-51 (Fed. Cir. 2011), involved a claimed invention addressing the problem of “making a nectar feeder with a movable divider to prepare different ratios of sugar and water for different animals.” The purpose of a first group of references was separating solid objects. But none of them showed a partitioned container adapted to receive water or contain it long enough to be able to prepare different ratios in the different compartments. A second group of references was directed to containers that facilitate mixing two separated fluids together. But the second group did not show a movable divider or the ability to prepare different ratios. The court ruled that an inventor considering the relevant problem would not have been motivated to consider any of the cited references. Accordingly, they were non-analogous and did not qualify as prior art for purposes of obviousness. Rejections of the claims were reversed.

There tend to be more disputes over application of the reasonably pertinent prong than the field of endeavor prong. But just as with the other prong, patentees and applicants are incentivized to define the relevant problem narrowly. Examiners and challengers may define the problem more broadly and generically. Reasonable pertinence rests on what is best supported by the relevant facts. For example, a statement of the relevant problem that is inconsistent with the discussion in a patent or application, viewed as a whole, is likely incorrect—whether broader or narrower than they way the disclosed invention was described. And extrinsic evidence from other patents, expert testimony, etc. can be used to establish pertinence. So even if a given patent is very short and says relatively little about problems faced in the art, other evidence might inform that inquiry.

Conclusion

The analogous versus non-analogous art question establishes whether or not a given reference qualifies as prior art for purposes of obviousness. But it is not applicable to use of the same reference for an anticipation/novelty analysis. This factual question is rarely explicitly discussed in practice and usually it is assumed that any cited art is analogous. That is partly because courts have generally taken an expansive view of what qualifies as analogous. But, at the end of the day, whether a reference is analogous or not is just one facet of the fact-intensive obviousness analysis. An obviousness position requires solid evidence and a good, logical argument. Reliance on non-analogous art is simply a type of bad argument resting on deficient evidence.

In my example of a fishing lure invention and a rocket fuel additive reference, the examiner eventually did acknowledge that his cited reference could not be relied upon for an obviousness rejection. It was bad optics. The argument that “this is not rocket science” when dealing with the patentability of a fishing lure invention was clearly a winning one (and a fun one to be able to make!). In particular, rocket science and fishing lure design and manufacturing were different fields of endeavor. And prior art about fuel additives designed to influence combustion properties had no bearing on the purposes of the fishing lure invention, which was intended to provide certain weighting characteristics during use without causing environmental pollution. So this was a stark illustration of non-analogous art.

Sometimes looking to disparate fields and combining teachings that were, individually, already known can be the product of true invention. Of course, on the other hand, sometimes an alleged invention is obvious and unpatentable. Simply because an applicant or patentee finds a cited reference to be inconvenient does not make it non-analogous art. The non-anlogous arts tests are occasionally useful as a way to draw the line between patentable and unpatentable ideas.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.