At a most basic level, patent infringement in the U.S. involves making, using, selling, offering for sale, importing into the USA a patented invention without authorization. Although there are some additional grounds for infringement that may apply in some other circumstances. All grounds for infringement fall into two general categories: direct infringement and indirect infringement. These categories refer to who is being accused and whether they are directly responsible or instead indirectly or partly responsible.

There are multiple types of infringement under each category. These include literal or Doctrine of Equivalents infringement, and, for indirect infringement, active inducement of infringement, contributory infringement, and certain activities related to components for export from the USA. Each of these provisions, set forth in § 271 of the U.S. patent laws, is taken up further below.

Direct Infringement

Direct patent infringement means that an accused party is directly responsible for infringement a patent. Direct infringement requires that each and every limitation (or element) of at least one claim of an asserted patent is met either literally or under the Doctrine of Equivalents. If a limitation of a given patent claim is not present in the accused product or process, either literally or equivalently, then that claim is not infringed.

The sorts of things that can constitute direct infringement include the following:

- making (that is, manufacturing) the patented invention in the USA (35 U.S.C. § 271(a))

- using the patented invention in the USA (35 U.S.C. § 271(a))

- offering to sell the patented invention in the USA (35 U.S.C. § 271(a))

- selling the patented invention in the USA (35 U.S.C. § 271(a))

- importing the patented invention into the USA (35 U.S.C. § 271(a))

- submitting a new drug application for U.S. regulatory approval (Hatch-Waxman Act; 35 U.S.C. § 271(e))

- importing into the USA, or offering to sell, selling, or using within the USA, a product which is made by a process patented in the USA, unless it is materially changed by subsequent processes or it becomes a trivial and nonessential component of another product (35 U.S.C. § 271(g))

- violations of certain additional rights to exclude specific to plant patents (35 U.S.C. § 163)

Normally, any of these infringing acts requires a single entity to satisfy each and every limitation of a claim. However, it is also possible to have vicarious liability for infringement in situations where there are multiple entities involved in the use of a patented method/process or the making or using of a patented system/device. Vicarious liability is a type of direct infringement stemming from principles of agency law, and includes principal-agent relationships, contractual arrangements, and joint enterprises. But it does not include joint tortfeasor liability. Vicarious liability depends on control exercised by the entity accused of infringement over other involved entities. Control is what makes vicarious liability for direct infringement differ from indirect infringement (discussed below), with only the latter encompassing arms-length transactions and/or independent action.

There are two ways of finding infringement of a utility or design patent that differ in terms of how the accused product or process compares to the scope of the claim(s) of the asserted patent:

- Literal Infringement

- Infringement Under the Doctrine of Equivalents (also called infringement by equivalence)

For a plant patent, infringement requires proving:

- asexual reproduction of the patented plant (by means other than from seeds, such as by the rooting of cuttings, by layering, budding, grafting, division, inarching, cloning, etc.)

The concepts of literal infringement and infringement under the Doctrine of Equivalents are not usually invoked for patent patents, due to infringement being narrowly applicable to the progeny of a patented plant through asexual reproduction that involves physical taking or appropriation of the patented plant’s biological material.

Literal Infringement

Literal infringement means that the accused product or process falls within the scope of the asserted claim(s) as construed by a court. Under U.S. law, infringement analysis is a two-step process. It involves, first, construing the claims to ascertain their meaning to a person of ordinary skill in the art and to resolve any ambiguities or disputes over that meaning, and, second, comparing the accused product/process to the properly construed claim(s). Literal infringement is present when the accused infringer meets each and every limitation (or element) of an asserted patent claim exactly, as properly construed. Any deviation from a claim limitation (as properly construed) precludes a finding of literal infringement.

Infringement Under the Doctrine of Equivalents

Under the Doctrine of Equivalents, a product or process that does not literally infringe upon the express terms of a patent claim may nonetheless still be found to infringe if there is “equivalence” between the elements of the accused product or process and claimed elements of the patented invention. This type of infringement arises when the accused product or process is outside the literal scope of at least one limitation of an asserted claim, as properly construed. Patentees rely on the Doctrine of Equivalents under the second step of the infringement analysis, if at all, only if literal infringement cannot be established. Otherwise, the Doctrine of Equivalents can apply to the same set of activities as for literal infringement.

This is an equitable doctrine meant to “temper unsparing logic” that “would place the inventor at the mercy of verbalism and would be subordinating substance to form.” It evolved in response to situations where accused infringers attempted to “practice a fraud on a patent” by introducing “minor variations to conceal and shelter the piracy.” Of course, the doctrine is in tension with the policy requiring that claims put the public on notice of a patent’s scope. This is a reason the Doctrine of Equivalents is not meant to be routinely invoked and is not applied broadly. In other words, this type of infringement is a limited exception to the general rule that patent claims must reasonably put others on notice of the outermost boundaries of what constitutes infringement. Put another way, it allows a limited form of “central” claim enforcement in a regime of “peripheral” claiming.

The Doctrine of Equivalents is applied individual claim limitations rather than to the claimed invention as a whole. To find infringement, each claim limitation (or element) must be found either literally or equivalently in the elements of accused product/process. This is called the “all elements” rule. The question of equivalence is inapplicable if a claim limitation is totally missing from an accused device. The Doctrine of Equivalents cannot be used to re-draft claims and effectively eliminate limitations entirely. Though this inquiry always revolves around what differences can reasonably be considered equivalent. An undue expansion of a patent’s claim(s) is not permitted. After-arising technology can potentially be encompassed by the Doctrine of Equivalents (unlike for means-plus-function equivalents).

There are two approaches to assessing equivalents: the “insubstantial differences” test and the “function-way-result” test. The function-way-result test (also called the “triple identity” test) says that equivalence may be present for a given element if the accused product/process performs substantially the same function in substantially the same way with substantially the same result. This is not the only way to assess whether differences are insubstantial, but it is particularly useful for certain types of inventions such as mechanical devices. For biochemical inventions, however, looking at substantial differences may sometimes be more appropriate than the function-way-results test.

There are numerous limits on the Doctrine of Equivalents, which are really beyond this basic introduction. But an extremely important limit on the availability of the Doctrine of Equivalents is prosecution history estoppel. Things that the patentee did or said when obtaining the asserted patent might limit the patentee’s ability to later rely on the Doctrine of Equivalents. So the Doctrine of Equivalents is not always or automatically available.

Indirect Infringement

Indirect patent infringement means that an accused party is causing or enabling someone else to infringe. It can apply when an accused infringer meets some but not all of the limitations (or elements) of an asserted patent claim. It includes three types of infringement, which differ in terms of what the accused indirect infringer is doing:

- Active Inducement of Infringement (35 U.S.C. § 271(b))

- Contributory Infringement (35 U.S.C. § 271(c))

- Supplying Component for Export for Combination Outside the USA (35 U.S.C. § 271(f))

Generally speaking, there are additional requirements that must be satisfied to establish indirect infringement that are not required for direct infringement. Those additional requirements vary depending on what type of indirect infringement is asserted.

Also, relevant limitations of asserted claim(s) can be assessed under either their literal scope or under the Doctrine of Equivalents, if available—see discussions above of literal and Doctrine of Equivalents infringement for direct infringement. This is really to say that the Doctrine of Equivalents may still apply to indirect infringement scenarios.

Active Inducement of Infringement

Actively inducing someone else to infringe a patent constitutes inducement of infringement. Specifically, “[w]hoever actively induces infringement of a patent shall be liable as an infringer.” (35 U.S.C. § 271(b)). This is a form of vicarious liability. Active inducement requires taking an affirmative steps to encourage infringement by another entity, as well as knowledge that the encouraged acts infringe the asserted patent. A key component of inducement is that it requires there be at least one direct infringer. But the difference here is that instead of suing the direct infringer, a different entity is sued for inducement.

Inducement commonly arises in situations involving claims to a method of using a product. Rather than sue the end user, which may be a potential customer, the patentee instead sues a competitor making and selling products used by others to (directly) perform and infringe the asserted method claim(s). It also sometimes arises where a corporate officer or owner induces his or her company to infringe, making that individual personally liable for infringement.

Contributory Infringement

Contributory infringement arises when selling, offering to sell, or importing components that are specially made or adapted for use to infringe a patent. However, contributory infringement excludes activities involving a staple article or commodity of commerce that is suitable for substantial noninfringing use. A “substantial noninfringing use” is any use that is not unusual, far-fetched, illusory, impractical, occasional, aberrant, or experimental. So there is normally no liability for selling general-purpose commodities, even if they could be used in making or using a patented invention.

“(c) Whoever offers to sell or sells within the United States or imports into the United States a component of a patented machine, manufacture, combination or composition, or a material or apparatus for use in practicing a patented process, constituting a material part of the invention, knowing the same to be especially made or especially adapted for use in an infringement of such patent, and not a staple article or commodity of commerce suitable for substantial noninfringing use, shall be liable as a contributory infringer.”

35 U.S.C. § 271(c)

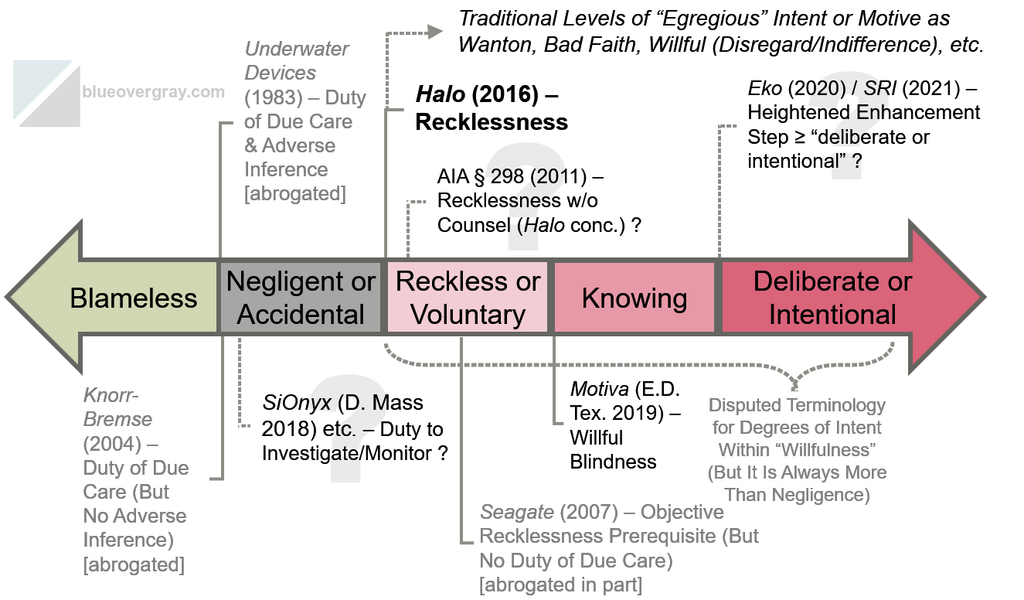

In order for contributory infringement to be present, the infringer must know that the combination for which his component was especially designed was both patented and infringing. This knowledge requirement differentiates contributory infringement from direct infringement, which does not require any such knowledge of the patent or infringement (except to enhance damages).

Contributory infringement is important for situations involving the sale of repair or replacement parts for use in or with patented products or methods.

Supplying Component for Export for Combination Outside the USA

Section 271(f) of the patent laws creates two grounds for infringement involving activities in the USA relating to products made in a foreign country. They arise when components of a patented invention are supplied for export from the USA. These grounds for infringement are similar to yet distinct from active inducement and contributory infringement, discussed above. But these provisions do not require that the equivalent of “foreign” direct infringement occur. That is, the actual combination need not actual occur. However, these provisions apply exclusively to apparatus claims, and are not available for method/process claims. They also do not apply to activities that occur entirely outside the USA. Also, § 271(f)(1) has a quantitative requirement about the number of components involved and it does not apply to only a single component.

“(f)

(1) Whoever without authority supplies or causes to be supplied in or from the United States all or a substantial portion of the components of a patented invention, where such components are uncombined in whole or in part, in such manner as to actively induce the combination of such components outside of the United States in a manner that would infringe the patent if such combination occurred within the United States, shall be liable as an infringer.

(2) Whoever without authority supplies or causes to be supplied in or from the United States any component of a patented invention that is especially made or especially adapted for use in the invention and not a staple article or commodity of commerce suitable for substantial noninfringing use, where such component is uncombined in whole or in part, knowing that such component is so made or adapted and intending that such component will be combined outside of the United States in a manner that would infringe the patent if such combination occurred within the United States, shall be liable as an infringer.”

35 U.S.C. § 271(f)

The grounds for infringement under § 271(f) are somewhat rarely invoked. This is largely because manufacturing costs are often higher in the USA than abroad. As a result, courts have not extensively clarified the scope and proper application of these provisions. But suffice it to say they may apply in situations where components are being produced and/or sold in the USA for export.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.