A version of this article previously appeared in Landslide magazine (Vol. 14, Issue 4, June/July 2022), published by the ABA Intellectual Property Law Section.

Introduction

What are the minimum requirements to establish enhanced damages for patent infringement after the passage of the America Invents Act (AIA) and the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Halo, and what evidence can be presented on this point? Post-Halo cases reveal areas of ambiguity and dispute. Some dispute involves willfulness theories falling close to the line between reckless conduct sufficient to establish willfulness and merely negligent conduct that is not willful. But a lingering ambiguity is how 35 U.S.C. § 298 may exclude from willful patent infringement certain conduct that might be considered reckless—and thus willful—in other areas of tort law. For whatever reason, § 298 has received little attention or treatment, which has even led to decisions contrary to that statutory provision.

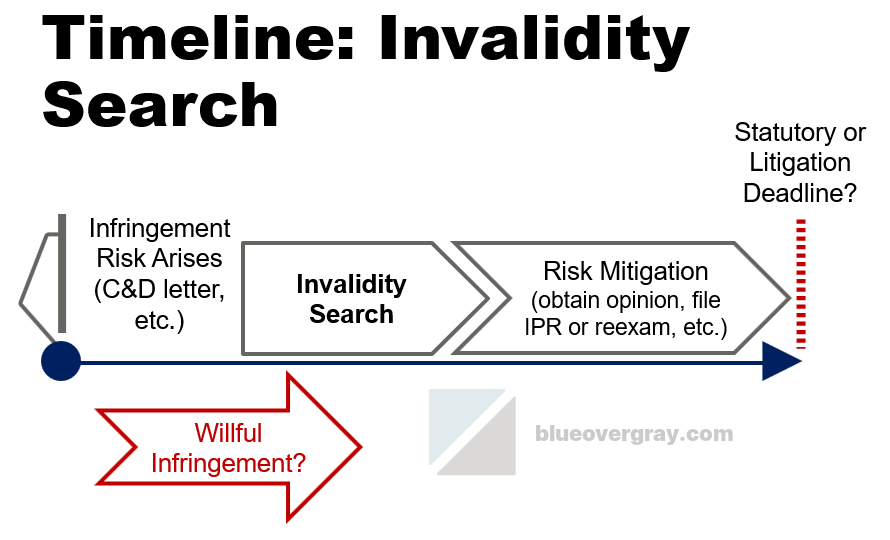

A Brief History of Willfulness

Let us begin with some context for how willfulness has evolved in patent law.[i] Damages enhancement is governed by 35 U.S.C. § 284, even though the term “willful” does not explicitly appear there. In the early 1980s, the Federal Circuit established an affirmative duty of due care and an adverse inference of willfulness if the accused infringer did not both obtain advice of counsel and waive privilege to present an advice of counsel defense.[ii] Decades later, the Federal Circuit abolished the adverse inference in Knorr-Bremse.[iii] Then it abolished the affirmative duty of due care in Seagate, substituting a two-prong willfulness analysis requiring “objective recklessness” as a prerequisite.[iv] In the aftermath of those cases, the AIA introduced § 298, which prohibits use of the failure to obtain advice of counsel or make an advice of counsel defense to establish willfulness (or inducement).[v]

In 2016, the Supreme Court in Halo threw out the “objective recklessness” prerequisite, finding its “inelastic constraints” insufficient to allow courts to punish “the full range of culpable behavior.”[vi] The Court held that “culpability is generally measured against the knowledge of the actor at the time of the challenged conduct.”[vii] Therefore, “[t]he subjective willfulness of a patent infringer, intentional or knowing, may warrant enhanced damages, without regard to whether his infringement was objectively reckless.”[viii] The Court discussed how reckless conduct supports punitive damages where willful intent is required while merely negligent conduct does not, clarifying that “a person is reckless if he acts ‘knowing or having reason to know of facts which would lead a reasonable man to realize’ his actions are unreasonably risky.”[ix] The abrogated “objective recklessness” threshold had allowed classically reckless conduct to be exonerated by after-the-fact rationalizations, which meant that some reckless conduct was inappropriately shielded from punitive enhanced damages.[x]

Later Federal Circuit cases have interpreted Halo as abrogating the “objective recklessness” requirement in a relatively narrow way but leaving intact much other pre-Halo case law,[xi] which presents challenges for anyone trying to parse out the way older cases may have been abrogated only in part but are potentially still controlling as to other aspects. The Federal Circuit has maintained that “willfulness” is a question of intent involving the accused infringer’s state of mind that is for the finder of fact (jury) to decide,[xii] and knowledge of the asserted patent is a prerequisite to a finding of willfulness.[xiii] After willfulness is established, the question of enhancement of damages is then a question for the court (rather than jury) to decide[xiv]—though a willfulness verdict does not automatically entitle the patentee to enhanced damages.[xv] But a court’s discretionary moral judgment regarding enhancement does not depend on any preceding factual finding of a particular state of mind or level of intent of the infringer.[xvi]

District court decisions post-Halo have begun to explore the minimum requirements to plead and then introduce evidence of willfulness, though the Federal Circuit has not yet reached some of the new theories definitively. These various new theories address what it means to subjectively “have reason to know” that accused conduct presents an unreasonable risk of patent infringement in the absence of direct evidence that the accused party actually knew about the patent and that there was a high probability its conduct infringed, as well as the effect of the accused taking affirmative steps to avoid learning of such facts.[xvii]

New Theories of Willful Infringement

First, a number of district courts have found “willful blindness” to be an acceptable theory of willful patent infringement. Motiva from the Eastern District of Texas is perhaps the most widely known of these cases, holding that “[s]ince the Supreme Court has explained that willful blindness is a substitute for actual knowledge in the context of infringement, it follows that willful blindness is also a substitute for actual knowledge with respect to willful infringement.”[xviii] Willful blindness has two basic requirements: (1) the accused must subjectively believe that there is a high probability that a fact exists, and (2) the accused must take deliberate actions to avoid learning of that fact; these two requirements mean willful blindness has a limited scope that surpasses recklessness and negligence.[xix] To avoid dismissal, patentees must make “plausible” willfulness allegations regarding both requirements for willful blindness.[xx]

What has generated much discussion about willfulness theories relying on willful blindness is the role of “no patent review” corporate policies that (at least on paper) bar employees from reviewing competitor patents.[xxi] Yet the mere existence of such a “no patent review” policy is not per se sufficient to plead willful blindness for willful infringement unless there is also a plausible allegation that the accused party subjectively believed a high probability of patent infringement existed.[xxii] In practical terms, this means there must be something more than simply a blanket corporate policy that applies to any and all (competitor) patents and that “something more” must plausibly suggest a culpable state of mind with regard to infringement of the asserted patent.

Second, some courts have addressed other theories—distinct from “willful blindness”—that an accused infringer should have reasonably known about the asserted patent. For example, district courts are divided about whether actual knowledge of an unasserted family-related patent coupled with an allegation that the accused should have investigated that patent family to discover the asserted patent—such as a broader continuation or broadening reissue—is sufficient to support willfulness.[xxiii] At times, these other theories appear uncomfortably close to the old, abrogated affirmative duty of due care.[xxiv] These other theories seem less stringent and more expansive than willful blindness, partly because they fall close to the boundary between negligence and recklessness but also because decisions on these theories often contain little or no discussion of why the accused had reason to know that there was infringement of a later-issued patent and not merely reason to know that the later-asserted patent existed.[xxv]

Statutory Limits on Evidence of Willfulness Under § 298

But what about § 298? A curious feature of many post-Halo willfulness cases is how little that section introduced by the AIA is discussed or even cited by courts when dealing with issues to which it directly relates, namely the relevance of evidence under the second Read factor: “whether the infringer . . . investigated the scope of the patent and formed a good-faith belief that it was invalid or that it was not infringed.”[xxvi] This is most troubling when courts proffer reasoning based on case law that was abrogated by § 298 (if not also by Seagate). Section 298 states:

“The failure of an infringer to obtain the advice of counsel with respect to any allegedly infringed patent, or the failure of the infringer to present such advice to the court or jury, may not be used to prove that the accused infringer willfully infringed the patent or that the infringer intended to induce infringement of the patent.”[xxvii]

There can be no question that § 298 excludes certain evidence from use to prove willfulness, including (1) the failure to consult an attorney and (2) the decision to maintain privilege over advice received from counsel. Yet an asymmetrical framework remains: the accused infringer is still free to obtain a legal opinion and later voluntarily present an advice of counsel defense based on that legal advice,[xxviii] but a “decision not to seek an advice-of-counsel defense is legally irrelevant under 35 U.S.C. § 298.”[xxix]

The key effect of § 298’s framework has to be that “having reason to know” for a (recklessness) willfulness theory must be limited to what the accused infringer reasonably should have known at the time without the assistance of counsel. The scope of the accused party’s (subjective) knowledge of the intricacies of patent law will vary considerably, though. For instance, lay parties might reasonably believe that broader later-issuing patents or reissues are not likely or that something like prosecution laches would apply to them.[xxx] This subjective knowledge may be difficult to even infer from circumstantial evidence in situations in which the accused did obtain advice of counsel but chooses not to waive privilege and not to make an advice of counsel defense based on that advice. And mere speculation on this point is generally inadequate. Moreover, as one district court held, attempts to suggest what the accused knew based on privileged communications not in evidence may be improper as a “disguised” attempt to circumvent the limits set forth in § 298.[xxxi] In a somewhat counterintuitive way, § 298 provides two distinct incentives to obtain advice of counsel because an accused party can either waive privilege in such advice and present an advice of counsel defense or maintain privilege and later potentially shield certain state of mind inquiries or inferences implicating that (maintained) privilege.[xxxii]

Does a Duty of Due Care Still Exist? And Does It Matter?

Seagate abrogated the affirmative duty of due care; but when Halo later abrogated the “objective recklessness” standard, a question arose as to the impact of Halo’s abrogation of the abrogation of the duty of due care.[xxxiii] The Federal Circuit has not explicitly weighed in on this point, and no Federal Circuit case since Halo mentions the term “duty of due care” at all. On the one hand, § 298 makes the existence or nonexistence of a judicially created duty of due care less important. But a real question remains about how patentee use of the second Read factor against an accused infringer may now be abrogated in whole or part. Can an accused party’s failure to conduct a nonlegal investigation of some sort regarding an asserted patent be used to establish willfulness today?

Worth mentioning at the outset is the Federal Circuit’s Broadcom case regarding induced infringement. There, despite the abolishment of the duty of due care, “[b]ecause opinion-of-counsel evidence, along with other factors, may reflect whether the accused infringer ‘knew or should have known’ that its actions would cause another to directly infringe, . . . such evidence remains relevant.”[xxxiv] This is not at all straightforward. At first blush, failure to meet an abolished/nonexistent duty of due care hardly seems relevant, logically if not legally. But in any event, the passage of § 298 abrogated precedent like Broadcom with regard to failure to obtain advice of counsel (or to present such a defense).[xxxv] But if the duty of due care only ever pertained to advice of counsel, then its abrogation (by statute or case law) might have left intact some separate due inquiry obligation under the second Read factor.[xxxvi]

Tending to complicate matters here are cases reaching conclusions plainly contrary to § 298, or reaching conclusions as to the boundaries and implications of that section without meaningful explanation. For instance, one district court ruled that “failure to produce . . . an opinion for trial can be considered as a factor in the jury’s determination of willfulness.”[xxxvii] Astoundingly, that court discussed old cases without any reference to their abrogation, and its ruling ended up permitting use of statutorily barred evidence for willfulness.[xxxviii] Moreover, a nonprecedential Federal Circuit decision discussed the second Read factor and found that a lack of investigation of asserted patents provided some evidence of willfulness, reaching that conclusion without discussing legal relevance limits under § 298.[xxxix]

Justice Breyer’s concurrence in Halo suggested that a nonlawyer analysis of an asserted patent might be enough to show a lack of willfulness,[xl] though the majority opinion was silent about that scenario. But that very issue came up in a district court case that held a willfulness verdict to be supported by evidence that “years of lucrative infringing sales [occurred] after failing to respond to the . . . licensing letter with a minimally adequate analysis of whether a license would be necessary,” which the court said was not prohibited by § 298 because the jury was instructed to disregard such matters, although the accused did try to present evidence of a nonlawyer invalidity analysis that the court excluded at trial.[xli] This illustrates the problem of courts too often suggesting what is in effect an adverse inference in jury instructions and then trying to immediately unring the bell by stating that no adverse inference of willfulness is permitted.

Yet a contradiction often remains. A more defensible formulation is that a jury’s inferences of knowledge of the asserted patent and of infringement can support a willfulness finding in the absence of countervailing evidence. That is, an accused infringer simply runs a greater risk of a willfulness finding if no advice of counsel defense or the like is pursued to rebut willfulness allegations because a jury can properly infer minimally sufficient knowledge and intent even in the absence of direct evidence on those points, and this does not require going so far as to assign any probative value to a failure to act. There is an important difference between willfulness being inferred from unrebutted circumstantial evidence and the failure to act (e.g., to investigate or seek legal advice) itself being treated as positive evidence of willfulness.

It is fair to distinguish the possibility of the accused making a nonlawyer analysis or inquiry defense to a charge of willfulness from an affirmative duty to do so. On its face, § 298 bars patentees from arguing about failures to obtain or present “advice of counsel” evidence.[xlii] But nothing in the literal text of § 298 bars evidence of a failure to conduct a lay investigation of an affirmative claim of infringement. Yet excluding evidence of nonlawyer investigations or analyses by the accused runs against Justice Breyer’s Halo concurrence, if not also the implicit framework of § 298.

In these senses, the question of what evidence is relevant and what, if any, quasi “duty of due care” investigation/analysis requirement remains under the second Read factor becomes significant. While cases have relied on investigative failures to support willfulness, the reasoning and justifications for such conclusions are often shaky at best or simply stated in a confusing manner. Courts will need to sort this out more definitively. But, for their part, patent litigation counsel need to be more consciously aware of these issues so they can be raised and argued when appropriate.

Key Takeaways

- Post-Halo, the Federal Circuit applies a two-step process to claims for enhanced patent infringement damages under § 284: willfulness is initially a question for the finder of fact, and then subsequent enhancement, if any, is at the court’s discretion.

- Failure to obtain or present an opinion of counsel cannot be used to prove willfulness, though obtaining an opinion can still be valuable to rebut charges of willful infringement; however, the value or necessity of nonattorney patent infringement and validity investigations is not yet clear.

- “Willful blindness” has been accepted by many district courts as a willfulness theory, but at the outset it requires plausible pleadings about the accused’s subjective belief that there was a high probability that the asserted patent both existed and was infringed and that the accused took deliberate actions to avoid learning of those facts; “no patent review” policies may or may not meet all of those requirements.

- District courts are divided over whether willfulness can be plausibly supported by a failure to monitor or investigate a patent family after learning about an unasserted patent in that family (in the absence of affirmative avoidance of facts akin to willful blindness).

- Relevance limits under § 298 have often been overlooked by courts but should be considered for evidentiary objections and motion practice.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.

[i]. See, e.g., Brandon M. Reed, “Who Determines What Is Egregious? Judge or Jury: Enhanced Damages after Halo v. Pulse,” 34 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. 389, 393–96 (2018).

[ii]. Underwater Devices Inc. v. Morrison-Knudsen Co., 717 F.2d 1380, 1389–90 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (“Where . . . a potential infringer has actual notice of another’s patent rights, he has an affirmative duty to exercise due care to determine whether or not he is infringing,” including “the duty to seek and obtain competent legal advice from counsel before the initiation of any possible infringing activity.”).

[iii]. Knorr-Bremse Systeme Fuer Nutzfahrzeuge GmbH v. Dana Corp., 383 F.3d 1337, 1345–46 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (en banc) (“Although there continues to be ‘an affirmative duty of due care to avoid infringement of the known patent rights of others,’ the failure to obtain an exculpatory opinion of counsel shall no longer provide an adverse inference or evidentiary presumption that such an opinion would have been unfavorable.” (citation omitted)).

[iv]. In re Seagate Tech., LLC, 497 F.3d 1360, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (en banc).

[v]. 35 U.S.C. § 298; see also Carson Optical Inc. v. eBay Inc., 202 F. Supp. 3d 247, 260–61 (E.D.N.Y. 2016) (§ 298 applies if the action is commenced on or after January 14, 2013); Halo Elecs., Inc. v. Pulse Elecs., Inc., 579 U.S. ___, ___, 136 S. Ct. 1923, 1936–37 (2016) (Breyer, J., concurring).

[vi]. Halo, 136 S. Ct. at 1933–34.

[vii]. Id. at 1933.

[viii]. Id. (citing Octane Fitness, LLC v. ICON Health & Fitness, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 1749, 1757 (2014)).

[ix]. Id.

[x]. Id. at 1932–35.

[xi]. E.g., WBIP, LLC v. Kohler Co., 829 F.3d 1317, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2016); WesternGeco L.L.C. v. ION Geophysical Corp., 837 F.3d 1358, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2016), reinstated, 913 F.3d 1067, 1075 (Fed. Cir. 2019); see also Halo, 136 S. Ct. at 1934–35.

[xii]. WBIP, 829 F.3d at 1341; Exmark Mfg. Co. v. Briggs & Stratton Power Prods. Grp., LLC, 879 F.3d 1332, 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (“[T]he entire willfulness determination is to be decided by the jury.”); Eko Brands, LLC v. Adrian Rivera Maynez Enters., Inc., 946 F.3d 1367, 1377–79 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

[xiii]. WBIP, 829 F.3d at 1341; see also SRI Int’l, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., 930 F.3d 1295, 1310 n.6 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (when willfulness began is a factual issue).

[xiv]. Seventh Amendment questions remain regarding holdings that a jury cannot determine egregiousness of conduct. Compare WBIP, 829 F.3d at 1341 n.13, and Eko, 946 F.3d at 1378, with Halo, 136 S. Ct. at 1933 and n.*. See also United States v. Murdock, 290 U.S. 389, 394 (1933) (“willfulness” is a set of states of mind), overruled in part on other grounds by Murphy v. Waterfront Comm’n of N.Y. Harbor, 378 U.S. 52 (1964); Howard Wisnia & Thomas Jackman, “Reconsidering the Standard for Enhanced Damages in Patent Cases in View of Recent Guidance from the Supreme Court,” 31 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 461, 473–76 (2015). Yet punitive enhancement is a discretionary moral judgment, not a factual question. See Smith v. Wade, 461 U.S. 30, 52 (1983).

[xv]. Halo, 136 S. Ct. at 1933; Presidio Components, Inc. v. Am. Tech. Ceramics Corp., 875 F.3d 1369, 1382 (Fed. Cir. 2017).

[xvi]. But questions arise where the Federal Circuit appears to suggest that certain levels of intent can support willfulness but not enhanced damages, which seems contrary to Halo. See SRI Int’l, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., 14 F.4th 1323, 1329–30 (Fed. Cir. 2021); see also Austen Zuege, “The Federal Circuit’s Standard for Enhanced Damages,” blue over gray (Oct. 12, 2021). This apparent discrepancy might allow courts to moot a jury’s willfulness finding. See Schwendimann v. Arkwright Advanced Coating, Inc., No. 11-cv-820, slip. op. at 50 (D. Minn. July 30, 2018).

[xvii]. See, e.g., Bos. Sci. Corp. v. Nevro Corp., 415 F. Supp. 3d 482, 495 (D. Del. 2019).

[xviii]. Motiva Pats., LLC v. Sony Corp., 408 F. Supp. 3d 819, 837 (E.D. Tex. 2019) (citing Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A., 563 U.S. 754, 769 (2011)).

[xix]. Global-Tech, 563 U.S. at 769–70; Motiva, 408 F. Supp. 3d at 837 (“By definition, willful avoidance requires more than mere recklessness—and Halo holds that recklessness alone is enough to show willful infringement.”).

[xx]. Bos. Sci., 415 F. Supp. 3d at 494–95; Nonend Inventions, N.V. v. Apple, Inc., No. 2:15-cv-466, 2016 WL 1253740, at *3 (E.D. Tex. Mar. 11, 2016), adopted, No. 2:15-cv-466, 2016 WL 1244973 (E.D. Tex. Mar. 30, 2016).

[xxi]. E.g., Charlotte Jacobsen et al., “Does Willful Blindness Beget Enhanced Patent Damages?,” Law360 (Feb. 28, 2020).

[xxii]. Nonend, 2016 WL 1253740, at *3; VLSI Tech. LLC v. Intel Corp., No. 18-cv-966, 2019 WL 1349468, at *2 (D. Del. Mar. 26, 2019); Ansell Healthcare Prods. LLC v. Reckitt Benckiser LLC, No. 15-cv-915, 2018 WL 620968, at *7 (D. Del. Jan. 30, 2018).

[xxiii]. Compare Vasudevan Software, Inc. v. TIBCO Software Inc., No. C 11-06638, 2012 WL 1831543, at *3 (N.D. Cal. May 18, 2012) (“requisite knowledge of the patent allegedly infringed simply cannot be inferred from mere knowledge of other patents,” such as “the [parent] patent, or, more generally, [the plaintiff’s] ‘patent portfolio’”), and Maxell, Ltd. v. Apple Inc., No. 5:19-cv-00036, slip op. at 9-10 (E.D. Tex. Oct. 23, 2019) (dismissing willfulness allegation based only on knowledge of application and not ultimately issued patent or knowledge of allowance of application), with SIMO Holdings Inc. v. Hong Kong uCloudlink Network Tech. Ltd., No. 1:18-cv-05427, slip op. at 7–9 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 29, 2019) (rejecting Vasudevan), and Oxygenator Water Techs., Inc. v. Tennant Co., No. 20-cv-358, slip op. at 8–13 (D. Minn. Aug. 7, 2020), and SiOnyx, LLC v. Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., 330 F. Supp. 3d 574, 609 (D. Mass. 2018).

[xxiv]. See, e.g., Schwendimann, No. 11-cv-820, slip. op. at 42 (duty of due care remains abrogated); Biedermann Techs. GmbH & Co. KG v. K2M, Inc., 528 F. Supp. 3d 407, 429 n.17 (E.D. Va. 2021) (noting abrogation issues and not intending to impose duty of due care; allegations were similar to willful blindness).

[xxv]. E.g., Oxygenator Water Techs., No. 20-cv-358, slip op. at 8–13 (passing over willful blindness to find failure to monitor/investigate willfulness theory plausible); Meridian Mfg., Inc. v. C & B Mfg., Inc., 340 F. Supp. 3d 808, 844 (N.D. Iowa 2018). But see Halo, 136 S. Ct. at 1936 (Breyer, J., concurring) (“‘[W]illful misconduct’ do[es] not mean that a court may award enhanced damages simply because the evidence shows that the infringer knew about the patent and nothing more.”).

[xxvi]. Read Corp. v. Portec, Inc., 970 F.2d 816, 827 (Fed. Cir. 1992), abrogated in part on other grounds by Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., 517 U.S. 370, 116 (1996).

[xxvii]. 35 U.S.C. § 298.

[xxviii]. Omega Pats., LLC v. CalAmp Corp., 920 F.3d 1337, 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2019); Ultratec, Inc. v. Sorenson Commc’ns, Inc., No. 13-cv-346, 2014 WL 4976596, at *2 (W.D. Wis. Oct. 3, 2014).

[xxix]. SRI Int’l, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., 930 F.3d 1295, 1309 (Fed. Cir. 2019); see also Halo, 136 S. Ct. at 1936–37 (Breyer, J., concurring).

[xxx]. See Cancer Rsch. Tech. Ltd. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 625 F.3d 724, 728–32 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

[xxxi]. Oil-Dri Corp. of Am. v. Nestle Purina Petcare Co., No. 15-C-1067, slip. op. at 5–6 (N.D. Ill. Mar. 8, 2019).

[xxxii]. See id. In contrast, enhanced damages were affirmed where the infringer delayed obtaining advice of counsel for years. Arctic Cat Inc. v. Bombardier Recreational Prods. Inc., 876 F.3d 1350, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2017). There, legal advice was (eventually) obtained and privilege waived, but the delay was held against the infringer.

[xxxiii]. See supra note xxiv.

[xxxiv]. Broadcom Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc., 543 F.3d 683, 699 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (holding that “failure to procure . . . an opinion [of counsel] may be probative of [subjective] intent”).

[xxxv]. 35 U.S.C. § 298.

[xxxvi]. See SRI Int’l, Inc. v. Advanced Tech. Labs., Inc., 127 F.3d 1462, 1464–65 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (“[T]he primary consideration is whether the infringer, acting in good faith and upon due inquiry, had sound reason to believe that it had the right to act in the manner that was found to be infringing.” (emphasis added)). Broadcom is still cited without mentioning its statutory abrogation. Omega Pats., 920 F.3d at 1352–53. Compare Broadcom, 543 F.3d at 699, with 35 U.S.C. § 298.

[xxxvii]. Visteon Glob. Techs., Inc. v. Garmin Int’l, Inc., No. 10-cv-10578, slip op. at 13–17, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 109564 (E.D. Mich. Aug. 18, 2016).

[xxxviii]. Compare id., with 35 U.S.C. § 298.

[xxxix]. WCM Inds., Inc. v. IPS Corp., 721 F. App’x 959, 970, 970 n.4 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (nonprecedential) (questioning cases suggesting no duty to predict what claims will issue from a pending patent applicable because prosecution histories are now normally publicly available); see also SIMO Holdings, No. 1:18-cv-05427, slip. op. at 5–7; 35 U.S.C. §§ 154(d), 284.

[xl]. Halo, 136 S. Ct. at 1936 (Breyer, J., concurring); see also Schwendimann, No. 11-cv-820, slip. op. at 42–43; Idenix Pharms. LLC v. Gilead Scis., Inc., 271 F. Supp. 3d 694, 699 (D. Del. 2017). But see SSL Servs., LLC v. Citrix Sys., Inc., 769 F.3d 1073, 1092 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (excluding lay testimony of belief in invalidity and noninfringement to rebut willfulness).

[xli]. Milwaukee Elec. Tool Corp. v. Snap-On Inc., 288 F. Supp. 3d 872, 886–88, 890–91 (E.D. Wis. 2017) (citing SSL, 769 F.3d at 1092).

[xlii]. Section 298 might only bar this evidence to initially prove willfulness but not its use in a subsequent enhancement determination.