Most people are well aware that patents are available. And patents are commonly known to relate to inventions. But what are the historical origins of patents and patent law? And, specifically, when did modern forms of patent laws emerge? The following is a short historical overview of how, and where, modern patent law developed, and how it was adopted in the USA.

Early Patents and the Emergence of Modern Patent Law

Patents have existed in some form for thousands of years, dating to at least 500 BCE in the ancient Greek city of Sybaris (located in what is currently Italy). But such ancient and other extremely old patents tended to differ in significant respects from the institutionalized patent laws of today. Then in medieval times patents began to emerge in a more modern form. Although such medieval patents appeared only on an isolated, erratic, and ad hoc basis, as with one in the city-state of Florence granted a single time around 1421 in response to an architect’s refusal to disclose an invention for an iron-clad ship without obtaining limited exclusive rights in it.

The very first modern patent law was in the Republic of Venice city-state in 1474, which provided ten year protection for “any new ingenious contrivance, not made heretofore in our dominion, as soon as it is reduced to perfection, so that it can be used and exercised . . . .” At that time, Venice had a mercantilist economy built on maritime trade, but also developed conditions for commercial capitalism. Although the city-state of Venice subsequently declined in world influence, without passing its legal customs on to many other states, its patent law was historically the first to institutionalize important characteristics of modern patents.

The British Statue of Monopolies enacted in 1624 is often considered the source for modern patent laws as adopted in the USA and through much of the world. It limited the ability of the British monarchy to grant “odious” long-term monopolies over entire industries, partly limiting letters patents to manners of “new manufactures” (inventions) for only a limited period of time. See Sears, Roebuck & Co. v. Stiffel Co., 376 U.S. 225, 229-30 and n.6 (1964). As a former British colony, it was British (rather than Venetian) legal norms that were adopted in the USA. See Pennock v. Dialogue, 27 U.S. (2 Pet.) 1 18,20 (1829).

These Venetian and English statutes established the concept of patents being based upon a quid pro quo. In exchange for disclosure of an invention its inventor could obtain a monopoly in that invention (and only that disclosed invention) for a limited time, thus preserving a general system of competition. This concept of patents as limited monopolies granted by governments (on behalf of the public) as an incentive to individual inventors in a competitive economy has been tied to the transition from feudalism to capitalism in European history. That is, the incentives to have modern patent laws tended to arise along with the historical emergence of capitalism.

History of the U.S. Patent System

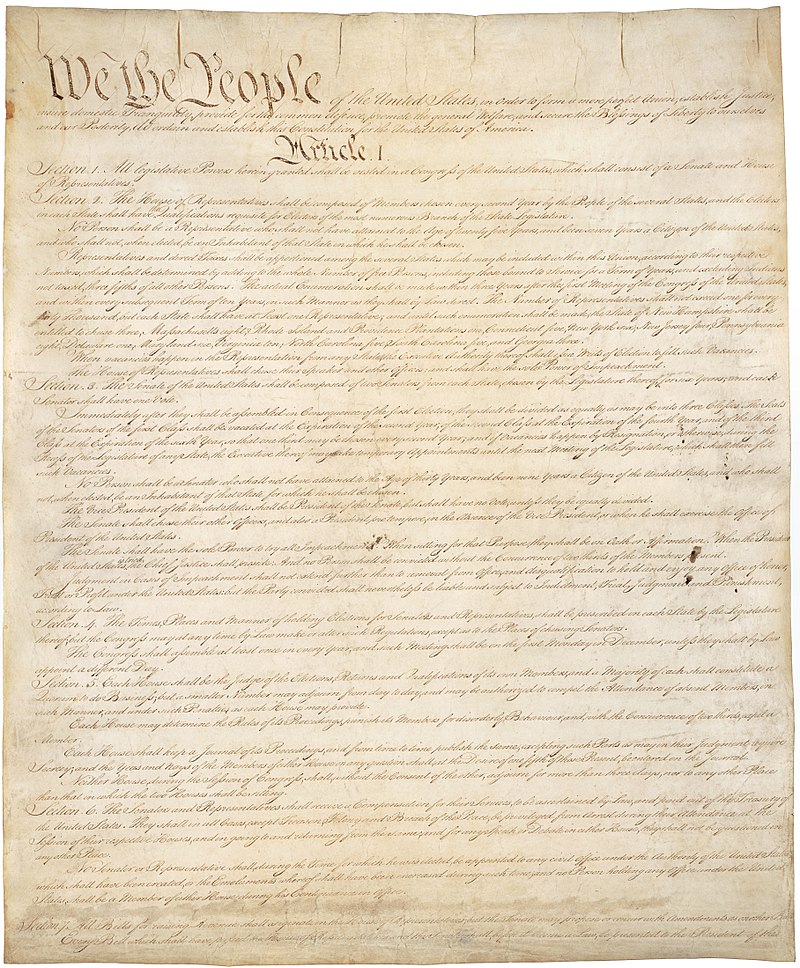

U.S. patent law was derived from English law. See Pennock, 27 U.S. at 18, 20. There is a patent and copyright clause in Article 1, § 8, clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution, granting congress the power “To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” This constitutional provision is both a grant of congressional authority and a limit on congressional authority. Trademark and trade secret law both lack such an explicit constitutional authorization.

Federal statutes providing for the granting of patents have been around since the very earliest days after U.S. independent from England—the first U.S. patent act was passed in 1790. The U.S. patent system has always sought to make patent fees reasonable, to allow ordinary people to apply for and obtain for patents on their inventions.

However, the U.S. Patent Office was not founded until 1810 (its first employee having been hired in 1802 as “superintendent of patents”) and modern pre-grant examination only began in 1836. This actually was a unique American contribution to patent law: the idea of institutionalized pre-grant examination of patent applications under established legal standards. Previously, U.S. patents were subject to either an erratic ad hoc pre-grant examination (from 1790-93, by a board initially comprised of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of War Henry Knox, and Attorney General Edmund Randolph) or were registered and patentability assessed only later in court when the patent was asserted (from 1793-1836).

Then, in the mid-Nineteenth Century, the U.S. Supreme Court established the concept of non-obviousness as a condition for patentability, which subsequently became a component of patent laws around the world. See Hotchkiss v. Greenwood, 52 U.S. (11 How.) 248 (1851). The U.S. Supreme Court also formally established other doctrines such as exceptions to patent eligibility. E.g., Le Roy v. Tatham, 55 U.S. (14 How.) 156, 175 (1852). Many of these concepts now exist in some form in the patent laws of many other countries.

The current patent laws are codified in Title 35 of the U.S. Code. These federal patent laws preempt state law, so there are no state patents or state patent laws. Though some peripheral issues around assignments, deceptive enforcement practices, etc. are still subject to state laws.

International Patent Harmonization

In contemporary times, most countries have some form of patent available. Even the former Soviet Union had forms of patents and inventor’s certificates as incentives. Patents generally remain territorial rights, limited to a particular country or region. This means patent laws do vary by country. But there are numerous treaties that have sought to harmonize some aspects of patent law between countries.

The most important patent-related treaties currently in effect are the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) provisions applicable to members of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property. For design patents (only), the Hague Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Industrial Designs is also significant. These treaties establish the basis for claims of “priority” when filing counterpart patent applications in foreign countries (under the Paris Convention), for instance. Other, less significant treaties exist that deal with formalities, procedures, classification systems related to patent publications, etc.

The Future of Modern Patent Law

The history of patent laws is still being written. Laws and treaties are amended and changed over time. There is not unanimous agreement on the best way to administer patents (or to have them at all). The proper scope and administration of the patent system have long been debated. These are often policy debates over who should benefit from the patent system, how much, and in what ways. Yet such disputes may not be apparent because they are often framed technocratic language about specific procedures and legal standards that conceal or deny their normative policy effects. Whenever laws involve a “balance” of interests some people seek to tilt it more in their favor.

For example, long ago that led to the U.S. Patent Office devoting considerable resources to preparing an agricultural report beneficial to rural areas to offset the perceived subsidy to urban areas provided by the patent system — eventually the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) was created as a spin off. Patent eligibility debates sometimes seem like efforts to obtain less limited monopolies or at least to expand them beyond technological inventions. Today, expansive use of patents has even been described as a neofeudal reversion (to a kind of pre-capitalist parcellated sovereignty).

Yet, despite various challenges and criticisms, the “modern” quid pro quo model that began in Venice still formally prevails as the justification for patent systems in much of the world, at least for now.

Need assistance with a patent, trademark, or other IP issue?

Contact Austen Zuege, an IP attorney who can help.