Introduction

Copyright notices have some legal value but are often not required in order to have copyright ownership. To understand generally what is meant by a copyright notice, consider the following example:

Copyright notice is optional for works published on or after March 1, 1989 (but was generally required for U.S. works published before then), unpublished works, and foreign works. But despite being optional for new and recent works, including a notice still provides various benefits. Bear in mind that while you probably see copyright notices in many places, ones that you come across (especially online) may not be in the correct form to constitute a formal notice under U.S. law.

We will first look at the benefits of using a copyright notice before turning to the specific elements required for a proper notice under U.S. law and the proper placement of a notice on copies of a given work. Formulating a proper notice for your own work will require gathering some relevant information and making some judgments. As will be seen, there are actually quite a number of factors that need to be considered in order to correctly provide all the required elements of a notice in order to gain all possible legal benefits. But even an erroneous copyright notice might have some value, if only as a potential deterrent against authorized use.

Benefits of Using a Copyright Notice

Although use is optional, providing a copyright notice has a number of practical and legal benefits for the copyright owner, including:

- Notice makes potential web site visitors aware that copyright is claimed in a given work, that is, it provides a “copy at your own risk” warning that may help discourage infringement;

- A notice may prevent an accused infringer from attempting to limit his, her, or its liability for certain damages in court based on an innocent infringement defense (17 U.S.C. §§ 401(d) and 402(d));

- Inclusion of a notice or other copyright management information (CMI) might provide an additional basis for monetary recovery if an infringer removes the notice (or other CMI) having reasonable grounds to know, that it will induce, enable, facilitate, or conceal infringement (17 U.S.C. §§ 1202 and 1203);

- It identifies the copyright owner for parties seeking permission to use the work (that is, it can help potential licensees find the owner and may prevent the work from becoming a so-called “orphan work”).

Another benefit, of sorts, is that copyright notices can freely be added to a work. A copyright registration is not required in order to utilize a copyright notice. And many times the process is simple enough that nearly anyone can add a copyright notice to a work without assistance. Although some effort is required to gather and confirm the information included in the notice, the cost to actually attached the notice to many types of works may be close to nothing, particularly for text-based works or those in digital formats.

In theory, copyright notices also provide a public benefit by identifying the year of first publication. That information might help determine when copyright in the work expires. But ever since the laws were changed such that omission of a notice (or use of certain erroneous notices) does not result in the loss of copyright, notices ceased to be reliable as an indicator of publication. And on top of that, now that the copyright term for many works is based on the life of the (last surviving) author, rather than publication, the formal elements of a copyright notice, alone, do not allow the term of copyright to be determined—though if an author’s name is listed the notice might help you start to investigate that author’s lifespan.

The Elements of a Proper Copyright Notice

Overview of Basic Requirements

A copyright notice is a statement placed on copies of a work to inform the public that a copyright owner is claiming ownership. A copyright registration is not required in order to utilize a copyright notice. A proper notice (under 17 U.S.C. §§ 401(b) and 402(b)) for a published work consists of three elements that generally appear as a single continuous statement in the following order:

- The copyright symbol © (the letter C in a circle), the word “copyright”, or the abbreviation “copr.” (or, for phonorecords, the symbol ℗ );

- The year of first publication of the work, though in the case of compilations, or derivative works incorporating previously published material, the year of first publication of the compilation or derivative work is sufficient; and

- The name of the copyright owner, or an abbreviation by which the name can be recognized, or a generally known alternative designation of the owner.

This example shows these three elements in a formal copyright notice:

We will look at each of these three basic elements of the notice in more detail below. Though the notice generally needs to be in the English language (with foreign words, such as the owner’s name, translated or transliterated into English).

Although certain old U.S. copyright laws required a copyright notice on published “United States works” in order to preserve copyright ownership, for any work created on or after March 1, 1989 a copyright notice is completely optional. And foreign works never required a notice under U.S. law.

It is possible to distinguish between general and specific copyright notices. A general notice might be applied to an entire book, or appear in the footer of all pages of a web site. Specific notices are directed at some specific part of something, such as an individual photo in a book or on a web page. Specific rather than general notices are usually not required, because the law makes any copyright notice optional. That holds even if a work includes material that is not copyrighted or owned by someone other than the owner identified in a general notice. However, where something includes both phonorecord and non-phonorecord works, multiple notices or at least multiple symbols in a single notice would be needed to fully obtain the legal benefits of notice because of the different requirements for the use of © and ℗ symbols in notices for those different types of works. And specific notices may be required based on the terms and conditions associated with use of particular content (such as license or other contractual terms). Also, U.S. copyright law includes certain prohibitions on removal of copyright management information (CMI), which may necessitate a specific notice in order to be compliant. For instance, frequently used “Creative Commons” copyright licenses (for instance, “CC BY 4.0”) include attribution requirements and prohibit removal of an existing copyright notice. So specific notices are more common when using content owned by someone else. But the explanation that follows applies to both general and specific notices.

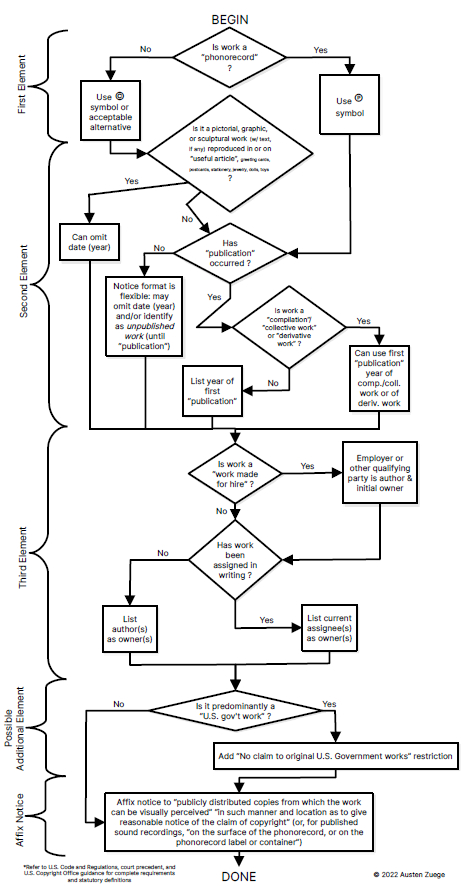

Flowchart

The following flowchart explains major determinations that should be made in order to establish the proper information specified in a copyright notice and to affix the notice on copies. It is important to note that the U.S. copyright laws include many special statutory definitions of words, which frequently differ from their meaning in ordinary conversation. Therefore it is critical to check the legal definitions of the words used in this flowchart. Also, there may be situations in which multiple types of works are involved meaning that the flow chart may need to be applied multiple times in order to fully assess proper notice requirements across all of the involved works.

Specific steps shown in this flowchart are explained in greater detail below.

First Element — Copyright Symbol © (or Acceptable Alternative) or Phonorecord Symbol ℗

The first element needed for a proper copyright notice is either the copyright symbol (or something recognized as an acceptable alternative) or the phonorecord symbol. (17 U.S.C. §§ 401(b)(1) and 402(b)(1)). So the first determination is whether the work in question is a “phonorecord” (as defined in 17 U.S.C. § 101: “material objects in which sounds, other than those accompanying a motion picture or other audiovisual work, are fixed . . . .”) or something else. Unless the work is an audio recording, it is probably not a phonorecord.

Though keep in mind that there are situations where use of multiple notices encompassing both symbols (© and ℗) are appropriate because both phonorecord and non-phonorecord works are present—like a music album containing a sound recording as well as liner notes. Alternatively, in certain situations involving audio recordings and non-audio works it is fairly common to see a single notice that uses both the © and ℗ symbols immediately adjacent to each other, which is something not explicitly provided for in the statutes but seems acceptable if the year of first publication and owner name are both identical for the phonorecord and non-phonorecord works.

The copyright symbol “©” is the letter C in a circle. The U.S. copyright statutes say that the word “copyright”, or the abbreviation “copr.” are acceptable alternatives to the copyright symbol. Using the letter C in parentheses, “(C)”, is technically not what the U.S. copyright statutes indicate. However, the U.S. Copyright Office has long considered “(C)” to be one of a few acceptable variants. Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, 3rd Edition, § 2204.4(A).

The phonorecord symbol “℗” is the letter P in a circle. The U.S. copyright statutes do not enumerate any acceptable alternatives. However, the U.S. Copyright Office has long considered “(P)” to be one of a few acceptable variants. Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, 3rd Edition, § 2204.4(A).

The copyright and phonorecord symbols (© and ℗) can either be copied-and-pasted into a notice or there are keystrokes that can be used to insert it while typing (these keystrokes vary depending on the computer system being used). Many word processing systems will auto-correct a letter C in parentheses sequence to the copyright symbol.

The term “All Rights Reserved” or the like is not an element of the notice prescribed by U.S. law, and it is not an acceptable variant or substitute for the copyright or phonorecord symbols (© or ℗). Instead, such a statement would be considered additional copyright management information.

Second Element — Year of First Publication

The second element of a proper copyright notice is the year of first publication of the work. (17 U.S.C. §§ 401(b)(2) and 402(b)(2)). What does or does not constitute “publication” under the statutory definition in the U.S. copyright laws is not straightforward, especially for digital and online works where the distinction between mere public display and actual publication is not always clear—and courts are divided on that question for works posted to the Internet by the copyright owner. (See Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, 3rd Edition, Chapter 1900 and § 1008.3 et seq.; and, e.g., Internet Prods. LLC v. LLJ Ents., Inc., No. 18-cv-15421 (D.N.J. Nov. 24, 2020)). But that is the most important consideration for the second element of the notice.

” ‘Publication’ is the distribution of copies or phonorecords of a work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending. The offering to distribute copies or phonorecords to a group of persons for purposes of further distribution, public performance, or public display, constitutes publication. A public performance or display of a work does not of itself constitute publication.

To perform or display a work ‘publicly’ means—

(1) to perform or display it at a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered; or

(2) to transmit or otherwise communicate a performance or display of the work to a place specified by clause (1) or to the public, by means of any device or process, whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times.”

17 U.S.C. § 101 Statutory Definitions of “Publication” and “To perform or display a work ‘publicly'” (emphasis added)

The U.S. copyright statutes say that in the case of “compilations” or “derivative works” incorporating previously published material, specifying the year (date) of first publication of the compilation or derivative work in the notice is sufficient. In other words, for a derivative work, such as a newer version of previously-published content, the more recent publication year for the newer version can be used. The same goes for a compilation. A “collective work” (in which a number of contributions, constituting separate and independent works in themselves, are assembled into a collective whole) or is a collection and assembling of preexisting materials that are selected, coordinated, or arranged in such a way that the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship, is a compilation and the same option to omit the year applies. The statues also say that a single notice is sufficient for a collective work.

If a work is unpublished, there is no year of first publication. The statutory requirements for the form and content of a copyright notice for a published work don’t apply to unpublished works. So copyright owners can technically use any form of notice they wish with an unpublished work. Some say that a copyright notice for an unpublished work should indicate the unpublished nature of the work in lieu of a year. Others say that the term “unpublished work” should be included in the notice in addition to specifying the year of creation. Though out in the real world, it is common to see copyright notices on unpublished works that include the year of creation rather than the year of publication without any express indication of unpublished status (even though this could be mistaken for the year of publication) or that only use the copyright symbol with the owner name. Because U.S. copyright statutes do not address the form of notices for unpublished works, there are no clear consequences to the copyright owner no matter how such copyright notices are formatted.

It is sometimes common to see a range of years used. For published works, the use of a date range is not something expressly addressed in the statute. Though as noted above, if the work is a collective work or a compilation (both of those terms are defined in the copyright statutes), then only the year of first publication of the compilation or collective work (and not those of the preexisting works) needs to be specified. And for unpublished works, there is no year of publication and no specific statutory framework for a proper notice.

The statute regarding copyright notices on (non-phonorecord) copies also includes an odd carve-out. The year (date) of first publication in a copyright notice may be omitted “where a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work, with accompanying text matter, if any, is reproduced in or on greeting cards, postcards, stationery, jewelry, dolls, toys, or any useful articles.” The term “useful article” has a statutory definition. So, depending on what sort of things the notice is applied to, it may be permitted to omit the year of publication. Though nothing prohibits including the publication year in such a notice anyway.

As a final note, the year is most often provided in Arabic numerals. Sometimes Roman numerals are used instead, most often with films and television programs (a practice that is thought to have originated as deception to obscure the age of the work).

Third Element — Name(s) of Copyright Owner(s)

The name of the copyright owner (or joint owners) is the third required element for a proper copyright notice. (17 U.S.C. §§ 401(b)(3) and 402(b)(3)). This is an area where mistakes are common in corporate settings, usually because of bad assumptions about who is actually the copyright owner.

Firstly, the owner or joint owners each need to be either an individual or a juristic entity (like a corporation). A brand name (trademark) is not a juristic entity, any more than a fictional character in a book or movie is one. The owner has to be a person or entity capable of legally owning property. Though a proper copyright notice can include variants, abbreviations, generally known alternative designations, or pseudonyms of the owner’s name, such as such as a legal assumed name or “dba” (doing business as) for a business or the diminutive/short form “Joe Public” instead of the full legal name “Joseph Public”. There also is a statutory provision for naming a producer that applies only for phonorecords.

But who is the true owner of a given copyright? This is the part that causes headaches. It might not be clear at all! It might (and often does in commercial settings) require a detailed review of legal provisions in relevant contracts and consideration of the factual context around the creation of the work(s) in question. If the person adding the copyright notice to a work does not know that information or have access to it, then someone else needs to be involved to establish the proper owner name for the notice.

Copyright ownership originally arises in the author(s) under U.S. law, and ownership of copyright is distinct from ownership of material object (a copy, even the sole “original” like a fine art painting). A work created by an individual author in an independent capacity is owned by that individual. Such situations are relatively straightforward. But the inquiry is more complicated in business contexts where corporations, employee/employer relationships, and vendor/contractor outsourcing may be present. A given work may be a “work made for hire” under U.S. law that shifts authorship and ownership of a work away from the individual(s) who prepared it. But work made for hire determinations can be difficult and highly confusing.

If an employee created the work within the scope of his or her employment, then it is a “work made for hire” and the employer is automatically deemed the author and copyright owner. That kind of work made for hire has two components that must both be satisfied: the work must have been prepared (1) by an employee (a status determined under general federal agency law) (2) within the scope of his or her employment. For example, the owner of a startup small business may not be an “employee” if her role is only that of an investor/shareholder without any job duties or receipt of salary/wages. And even someone who is an employee may not have created the specific work(s) in question within the scope of his or her employment. For instance, a work created by a person in her spare time with no relationship to her job duties would not be within the scope of her employment.

If a vendor (or contractor) created the work, then the vendor would usually be the author and own the copyright in the absence of a written assignment—unless authorship and ownership instead reside in the vendor’s employee(s) or subcontractor(s). The mere fact that the vendor/contractor was paid to create the work does not transfer ownership of copyright. Work-made-for-hire provisions dealing with employee-prepared works do not apply because contractors and vendors are not employees. Though work-made-for-hire provisions might make a corporate vendor the owner of works the vendor’s employees prepare. It is possible to agree in writing in advance to make certain types of works a “work made for hire” for which the purchaser is deemed the author (and owner), but only for nine types of works enumerated by statute (17 U.S.C. § 101). If the work is not one of the nine statutory types, a contract with a vendor/contractor (erroneously) purporting to create a work made for hire has no legal effect and ownership still rests with the vendor/contractor (or its employee or subcontractor) until a written assignment is executed.

If there are agreements in place with a vendor/contractor, they may or may not actually transfer ownership of copyright. Sometimes vendor/contractor agreements establish only an obligation to assign (such as when they use language referring to future actions, like “will own” or “will assign”), and therefore require a further written assignment to actually transfer copyright ownership. Or sometimes these agreements include an ineffective work made for hire provision that fails to actually transfer ownership of copyright (because the work is not one of the nine statutory types). Tracking down copyright ownership information can be time-consuming. For instance, master services agreements might incorporate separate “statement of work” documents that identify assigned works and those might all need to be reviewed in order to determine who owns what.

Possible Additional Element — Restrictions/Exclusions, Terms of Use, Etc.

Although the U.S. copyright statutes specify three elements required for a copyright notice, there might be other information included in addition. Only one of these additional elements is required under the U.S. copyright statutes to have a proper notice, and that situation is not common. Though additional elements included along with (or adjacent to) a copyright notice might be desired. The law does acknowledge the potential use of various additional copyright management information (CMI).

For instance, there might be an exclusion stated. A copyright notice with an exclusion is referred to as a restricted notice. A semi-common one, which stems from a statutory requirement for works consisting predominantly of re-used work(s) of the (federal) U.S. Government (for which there is no copyright), is “No claim to original U.S. Government works.” But there could be others, such as “© 2000 Jane Doe, no copyright claimed in illustrations” or “© 2000 Jane Doe, no copyright claimed in public domain photo.” Generally there is no need to include a restriction or exclusion unless the work is predominantly or significantly made up of materials not owned by the entity in the copyright notice.

Different kinds of additional CMI can be provided along with the copyright notice too. For instance explicit statements granting certain authorizations or licenses but prohibiting other things—that is, terms and conditions for use of the work—might be specified adjacent to the copyright notice, if desired.

Placement of a Copyright Notice

A copyright notice needs to be placed on copies of a work in a way that people are reasonably likely to see it. The U.S. statute about copyright notices for most types of works says:

The notice shall be affixed to the copies in such manner and location as to give reasonable notice of the claim of copyright. The Register of Copyrights shall prescribe by regulation, as examples, specific methods of affixation and positions of the notice on various types of works that will satisfy this requirement, but these specifications shall not be considered exhaustive.”

17 U.S.C. § 401(c)

The regulations referred to in the statute are found at 37 C.F.R. § 202.2. They include a large number of examples that pertain to particular types of works in specific ways. There are examples for works in book form, works reproduced in machine-readable copies, contributions to collective works, motion pictures and other audiovisual works, and pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. But, in general, the acceptability of a “reasonable” notice depends upon its being permanently legible to an ordinary user of the work under normal conditions of use, and on being affixed to copies in such a manner and position that the notice is not concealed from view upon reasonable examination. Where a notice does not appear in one of the precise locations described in the regulation’s specific examples, but a person looking in one of those locations would be reasonably certain to find a notice in another somewhat different location, the Register of Copyrights considers it acceptable.

The regulations give examples of defective notices as:

- those permanently covered so that they cannot be seen without tearing the work apart,

- those illegible or so small that they cannot be read without the aid of a magnifying glass (except where the work itself requires magnification for its ordinary use), and

- those placed on a detachable tag, wrapper, or container that is not part of the work and will eventually be detached/removed and discarded when the work is put in use.

The statutory benefits that arise from use of a copyright notice are not affected by the removal, destruction, or obliteration of the notice from any publicly distributed copies (or phonorecords) done without the authorization of the copyright owner. (17 U.S.C. § 405(c)).

For phonorecord copyright notices, the relevant statute provides that “The notice shall be placed on the surface of the phonorecord, or on the phonorecord label or container, in such manner and location as to give reasonable notice of the claim of copyright.” (17 U.S.C. § 402(c)).

Failure to include a proper copyright notice, or the use of a notice with erroneous information, is more significant for works published before March 1, 1989. There are various additional provisions governing those situations.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.