By Austen Zuege

What follows is the ultimate guide to patent marking in the United States. Marking is optional but can provide significant benefits to the patent owner in the event there is infringement. Not only are there practical burdens associated with marking patent products, there can also be questions about the legal requirements for proper patent marking notices. This patent marking guide aims to address both legal requirements and practical considerations for patentees. A shorter overview is available here, and a related presentation with other examples is available here.

Table of Contents

- Basic U.S. Marking Requirements

- Policy Behind the Marking Requirement

- Actual Notice: An Alternative to Marking

- Constructive Notice Through Patent Marking

- Possible Exceptions to Marking Requirements

- All Patentees Must Mark

- Licensee(s) and Other Authorized Parties Must Mark Too

- How to Implement Patent Marking: Two Possibilities

- Pre-Grant Marking

- False Patent Marking Prohibited

- To Mark or Not to Mark?

- Implementing a Marking Program

Basic U.S. Marking Requirements

Patent marking can be important for obtaining full recovery of infringement damages from an infringer. When enforcing a patent in the United States, damages for infringement of a patented article can usually be recovered only from the date the infringer had actual or constructive notice of the patent(s), whichever comes first, and no more than six years prior to bringing such a claim for damages in court.[1]

The statutory marking requirement comes from § 287(a) of the patent laws, which provides:

“Patentees, and persons making, offering for sale, or selling within the United States any patented article for or under them, or importing any patented article into the United States, may give notice to the public that the same is patented, either by fixing thereon the word ‘patent’ or the abbreviation ‘pat.’, together with the number of the patent, or by fixing thereon the word ‘patent’ or the abbreviation ‘pat.’ together with an address of a posting on the Internet, accessible to the public without charge for accessing the address, that associates the patented article with the number of the patent, or when, from the character of the article, this can not be done, by fixing to it, or to the package wherein one or more of them is contained, a label containing a like notice. In the event of failure so to mark, no damages shall be recovered by the patentee in any action for infringement, except on proof that the infringer was notified of the infringement and continued to infringe thereafter, in which event damages may be recovered only for infringement occurring after such notice. Filing of an action for infringement shall constitute such notice.”

35 U.S.C. § 287(a)

These statutory marking requirements apply to all types of U.S. patents: utility, design, and plant.

Explanations of what constitutes actual notice and how to properly mark patented articles to provide constructive notice are provided below.

Policy Behind the Marking Requirement

The marking requirement is meant to protect the public’s ability to exploit an unmarked product’s features without liability for damages until a patentee provides either constructive notice through marking or actual notice.[2] More specifically, marking requirements serve three related purposes: 1) helping to avoid innocent infringement; 2) encouraging patentees to give notice to the public that the article is patented; and 3) aiding the public to identify whether an article is patented.[3]

Actual Notice: An Alternative to Marking

Actual notice requires the affirmative communication of a specific charge of infringement by the patentee to the accused infringer, such as in a demand or cease-and-desist letter.[4] In this sense, actual notice (pre-suit) requires proactive communication by the patentee to the accused infringer to enable “proof that the infringer was notified of the infringement and continued to infringe thereafter.”[5] The marking statute also explicitly provides that “[f]iling of an action for infringement shall constitute such [actual] notice.”[6] So, at a minimum, the commencement of an infringement lawsuit will cause damages to accrue going forward.

Constructive Notice Through Patent Marking

Marking patented articles provides constructive notice to the public that an article is patented. This is called “constructive” notice because it does not matter whether or not an infringer actually saw the patent marking notice, only that the patentee marked patented articles appropriately. To be sufficient to establish constructive notice, the patentee must be able to prove that substantially all of the patented articles being distributed were properly marked, and, once marking began, that the marking was substantially consistent and continuous.[7] If marking is defective at first, curing those defects going forward is possible. But full compliance with marking requirements sufficient to provide constructive notice to infringers is not achieved until the time the patentee “consistently marked substantially all” of the patented products, and if marking was deficient for a time then constructive notice will not be provided unless and until proper marking occurs with subsequent sales.[8]

Possible Exceptions to Marking Requirements

The most important exception to the marking requirement is where the patentee has not sold any patented articles. When there are no products to mark, there is no failure to mark and therefore no bar to recovery of pre-suit damages.[9] A patentee who has not sold anything under a patent can still recover back damages despite having not literally marked any products.

Additionally, because the marking statute refers only to a “patented article”, patents with method or process claims are treated differently. Courts have said that neither marking (constructive notice) nor actual notice is required to obtain back damages for infringement of asserted patents having only method or process claims.[10] For patents having both apparatus and method claims, marking may still be required to establish constructive notice depending on which claims are asserted in an infringement lawsuit.[11] In light of that standard, it is recommended to mark products whenever a relevant patent contains an apparatus claim.

Whether digital products that exist only electronically count as an “article” that a patentee must mark has not yet been definitively settled. But some courts have said that a patentee must mark a website either where the website is somehow intrinsic to the patented device or where the customer downloads patented software from the website. It is recommended to treat downloadable and online system inventions as articles that require marking whenever the patentee provides something important to operation of the invention and the relevant patent’s claims are not exclusively method claims.

Lastly, there is a “rule of reason” exception of sorts that may apply to a failure of a licensee or other authorized third party to substantially consistently and continuously mark despite reasonable efforts by the patentee, as discussed below.

All Patentees Must Mark

If a patent is assigned, the marking requirement applies to all patentees in the chain of title. That includes subsequent assignees. This is consistent with actual notice requirements. And this would appear to be the case despite changes to the marking statute over time to eliminate explicit further reference to assignees that appeared in earlier versions. Moreover, if a prior owner of a patent sold patented articles, that would appear to trigger a marking obligation that would impact the accrual of damages recoverable by any later assignee. Therefore, if unmarked articles were sold by a prior owner, a subsequent owner would need to cure defective marking through subsequent distribution of marked articles in order to establish constructive notice from the time defective marking was cured.

Courts do not seem to have addressed a situation in which there are co-owners of a patent and less than all of them have marked patented articles. Nonetheless, because all co-owners are patentees, and because all co-owners must join an infringement lawsuit (and any co-owner can unilaterally block such a suit), co-owners independently selling patented articles are each subject to a marking requirement. This means that in order for damages to accrue before actual notice of infringement, the sufficiency of marking should be assessed by looking at marking-related activities by all patent co-owners collectively. It is therefore recommended to ensure that all co-owners of a patent mark.

Licensee(s) and Other Authorized Parties Must Mark Too

Marking requirements apply not only to the patentee but anyone making, selling, or offering for sale the patented article “for or under” the patentee or importing it into the U.S.[12] This includes the types of things that can constitute direct infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 271(a) (except for mere “use”).

Where a patent is licensed to another, expressly or impliedly, or there is a covenant not to sue or the like, the other entity is required to mark as well.[13] Authorized activities by an outsourced manufacturer or authorized seller, or even certain explicitly or impliedly licensed customers, are treated as if they are by the patentee in terms of marking requirements in this respect. Failure of a licensee to consistently mark substantially all licensed products will frustrate efforts to establish constructive notice. However, because third parties are implicated, this requirement is subject to a rule of reason.[14] A court can excuse some instances of omitted marking by others and still find constructive notice satisfied if the patentee made reasonable efforts to ensure compliance with marking requirements.[15]

Care should be taken whenever there are other entities involved with making, selling, offering for sale, or importing into the U.S. a patented article intended to be marked. It is recommended that any license for a U.S. patent, or a covenant not to sue under the patent, obligate the licensee or other party to comply with marking requirements.[16]

The applicability of marking requirements to things that can constitute indirect infringement such as active inducement of infringement and/or contributory infringement is less clear.

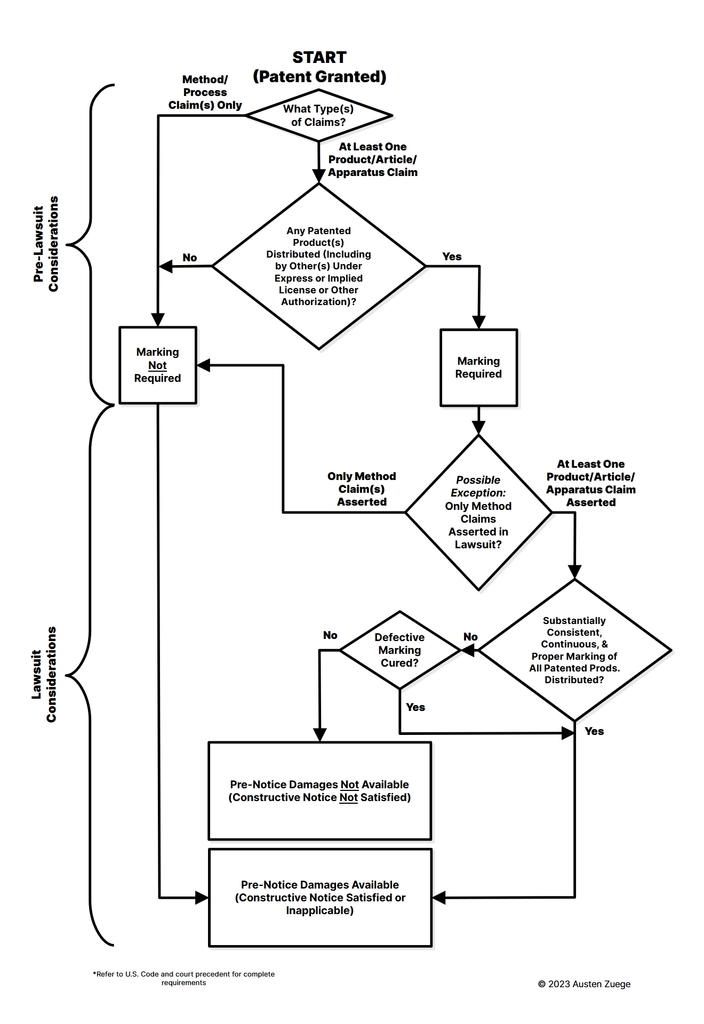

Summary of Marking Requirements for Pre-Notice Damages

The following flow chart summarizes the basic requirements of when patent marking is require to accrue infringement damages prior to the patentee affirmatively placing the accused infringer on actual notice (i.e., pre-notice damages).

How to Implement Patent Marking: Two Possibilities

There are two ways to mark patented articles in accordance with U.S. law: physical or virtual marking.

Physical Marking

Physical (or conventional or traditional) patent marking involves fixing notices on the patented articles themselves in a way that associates the patented article with the number of the patent.[17] Such a notice must include the word “patent” or the abbreviation “pat.”, together with the number(s) of the patent(s).[18]

If the character of the patented article means such a notice cannot be fixed to the patented article itself, such as due to size constraints, interference with operation (e.g., bio-compatibility of implantable medical devices) or where the article is a fluid or powder, the notice can alternatively be placed on a label fixed either to the patented article or to a package containing one or more of the patented articles—a notice included only in an accompanying manual or instructions may be sufficient as a form of label.[19] This is an alternate form of physical marking that is appropriate if (and only if) there is a legitimate reason the marking notice cannot be directly fixed to the article. But this alternative is not always and automatically permissible if the article itself can be marked. If marking on packaging or a label used, the patentee should be prepared to articulate a reason why marking on the article itself was not practical. That reason should involve more than convenience and/or subjective preference, and should be established or apparent at the time marking decisions are made. For plant patents, use of a notice on a label/tag or package would seem to be the only conceivable way of implementing patent marking under typical commercial circumstances—although painted-on or nailed-on markings might be possible in certain contexts such as for larger patented plants like mature trees.

It does not appear that courts have specifically interpreted what constitutes a “label” as opposed to fixing a marking notice “thereon” a patented article. But, in context, it seems fair to say that such a “label” refers to something that is only temporarily connected to the article, like a removable hang tag, just as a package is normally separated from an article it initially contains after purchase. In other words, the important point would seem to be the permanence of the the patenting marking notice in terms of the patent marking notice remaining fixed to the article during its useful life—similar to issues associated with defects in copyright notices. It does not appear that the statute narrowly requires etching, embossing, inscribing, molding, or otherwise integrally and monolithically forming the marking on the patented article. Rather, a plate, badge, or sticker that is permanently attached to the article, such as a marked metal plate riveted, welded, or permanently adhered to the article, would seem to qualify as being fixed “thereon” rather than being a “label” as an alternative to the primary form of physical marking. In contrast, a marking sticker temporarily secured with pressure-sensitive adhesive to a patented article in a location in which it would interfere with the use or enjoyment of that article if left in place and having a protruding tab to facilitate and encourage removal upon purchase would instead likely be a “label”.

If patent marking is provided on packaging, use caution with respect to what is included within the marked package. A package containing both patented and unpatented articles should not be marked in a way that creates confusion about which articles are subject to which patent(s) and/or deceives the public about which of those article(s) are patented. The same issues can arise when there is a question about patent(s) covering the packaging or label itself rather than the article contained inside or to which the label is attached. Such situations can raise questions of false marking, which is discussed below.

Marking requirements stem from what is recited in the claims of the relevant patent(s) and what patented articles are being commercialized. This requires first interpreting the scope of the patent claims and then comparing those properly construed claims to a given article to determine if the patent applies to it. For instance, depending on what is claimed in a given patent, a marking notice may need to be included on individual parts sold separately, such as wear parts, add-ons, or the like. When both an entire device and a piece part for that device are separately recited in different claims of a given patent, sale of the piece part by itself would give rise to an obligation to mark that individual part, while sale of the entire device would create an obligation to mark that likely would not be satisfied by marking only an internal piece part in a way that is not visible.

An example of a proper physical patent marking notice (for the fictitious U.S. Pat. No. 00,000,000) is the following fixed directly on an article covered by the claims of the indicated patent:

Pat. 00,000,000

If multiple patents apply to the same patented article, they can be listed together. It is not necessary to repeat the word “patent” or abbreviation “pat.” before each patent number in such a list. Court decisions are generally unconcerned with the word “patent” being pluralized in the notice, as well as with the addition of a word or abbreviation, such a saying “patent number 00,000,000” or “pat. nos. XX,XXX,XXX and YY,YYY,YYY” in a marking notice. After all, the point is to provide public notice not simply the unthinking repetition of certain words and numbers in isolation. The use of “U.S. patent” or “U.S. pat.” is acceptable, and might be worthwhile for products sold or shipped internationally. Though the text of the notice should be readable in English, because the statute explicitly uses English words and does not explicitly permit translations.

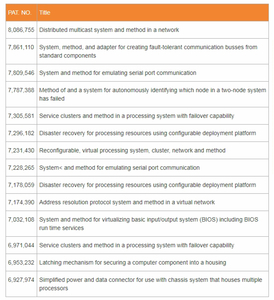

A patent marking notice fixed directly to a flip-top cap product (for use to close a container) is shown in the following photo. The notice is molded directly into the material of the article. It reads, “PAT. NO” followed by a list of one design patent number and one utility patent number separated by a semicolon. This type of traditional marking notice fixed directly on a patented article is acceptable under U.S. law.

![Redacted photo of patent marking notice on bird feeder product, which reads, "PAT. NO D[],407 ; 7,[]267"](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/patentmarkingnoticecapredacted-1024x462.jpg)

In the following example, a patent marking notice is fixed directly to a key ring product is shown. The notice is stamped directly into the metal of the article. It reads, “U.S.PAT.NO.” above a slot and control knob slider followed by one utility patent number below the slot and control knob slider. This type of traditional marking notice fixed directly on a patented article is acceptable under U.S. law. The fact that the patent number is on an opposite side of the slot from the “U.S.PAT.NO.” should be acceptable, because those two portions of the notice are still in close proximity and people viewing the notice would be likely to understand that the number (which is the only number appearing on the article) is the applicable U.S. patent number. Also, the lack of spaces between the abbreviated words should still be acceptable. The format of this notice was likely influenced by aesthetic concerns, to keep the key ring fob “clean” except for the area immediately adjacent to the slot and control knob slider

![Redacted photo of key ring product with patent marking notice that says "U.S.Pat.No. 5,[],366"](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/keychainmarkingredacted-300x294.jpg)

The following are two different examples of patent marking notices fixed directly to bicycle chamois shorts. In both instances, the marking notices are embossed directly in the chamois pad, inside the shorts. In the first (upper) example, the notice reads “Pat #” followed by a patent number, while in the second (lower) example, the notice reads “US PATENT #” followed by a patent number. The first example uses spaces rather than commas in the patent number, which is probably acceptable because it is still recognizable as a single patent number. Both examples use the number sign “#” (also called a hash or pound sign), which seems acceptable as a symbol commonly used as an equivalent to the word “number”. However, in the second (lower) example, the numbers of the patent are difficult to read due to the texture of the material in which they are embossed. While the form of both of these types of traditional marking notice fixed directly on patented articles are probably acceptable under U.S. law, poor legibility, and durability are factors to consider. A marking notice that is not reasonably legible may not provide constructive notice. Notices that become worn away or degraded due to extended use are likely not improper if they were originally fixed on the articles in a manner that is reasonably durable. But, in contrast, notices that are easily wiped away, smudged, or otherwise lack integrity when it comes to legibility may raise concerns about sufficiency for providing constructive notice, particularly if the patentee was aware of that the marking notice was in a physical form that was not reasonably durable. As an example, a marking notice written in pencil on a patented article in a way that immediately rubs off with contact might not be considered “fix[ed] thereon” (even if it might still be considered “mark[ed] upon” as stated in the false marking statute).

![Redacted photo of patent marking notice on bicycle shorts chamois pad, reading "Pat # 6 [] 618"](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/patentnumbermarkingshorts-1024x249.jpg)

![Redacted photo of patent marking notice on bicycle shorts chamois pad, reading "US PATENT # 6,[],702"](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/patentnumbermarkingshorts2-1024x288.jpg)

The following is an example of a patent marking notice fixed directly to a bird feeder product. Here, the notice is permanently printed directly on the product, on the exterior of a clear cylinder that is readily visible. It reads, “US Patents” followed by a list of five patent numbers separated by semicolons and then concluding with “and patents pending”. This type of traditional marking notice fixed directly on a patented article is acceptable under U.S. law.

![Redacted photo of patent marking notice on bird feeder product, which reads, "US Patents 6,[],707; 6,[],384; 6,[],192; 7,[],731; 7,[],982 and patents pending"](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/patentmarkingnoticebirdfeederredacted-1024x177.jpg)

The same bird feeder product depicted above was sold in a box, depicted below, that also carried a patent marking notice printed on it with some (but not all) of the same patent numbers listed as on the product itself. In this example, the package contained only a single product and the product had to be removed from the box for use. After removing the product the box would most likely be discarded. The notice states, “Protected by U.S. Patents” followed by two patent numbers separated by the word “and” and concludes with “and Patents Pending.” This particular box carried the depicted patent marking notice on a side panel near a discussion of trademarks, a country of origin indication, and other information. The product was sold by a Canadian company and an opposite side of the box included French-language text with the same patent marking notice in French. The alternate language marking was most likely included to comply with language laws in parts of Canada.

![Redacted photo of bird feeder product package (box) with the patent marking notice "Protected by U.S. Patents 6,[],707 and 6,[],384 and Patents Pending" printed on it.](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/patentmarkingbirdfeederboxredacted-1024x152.jpg)

The type of traditional marking notice fixed on the product packaging box pictured above, by itself, would likely be insufficient under U.S. law. That is because the character of the product itself is capable of being marked. Indeed, the product inside this box did carry a patent marking notice. So the marking notice on the package was not the only one. There is no prohibition against additional, redundant patent marking notices on packaging, if accurate. Incompleteness of the marking notice on the package would likely not preclude establishing constructive notice, although it would be preferable to have all notices be complete to avoid confusion and to potentially help establish willful infringement.

![Redacted photo of dental floss package that says "U.S. Patent 7,[],903"](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/flossmarking-1024x471.jpg)

The photo above is an example of a patent marking notice fixed to a package for dental floss. This notice is printed in permanent ink on a bottom exterior surface of a paperboard package. It reads, “U.S Patent 7,[],903”. This type of traditional marking notice fixed on the package containing the patented article is acceptable under U.S. law, because the character of dental floss does not permit marking the floss directly.

Virtual Marking

The Basics of Virtual Patent Marking

Virtual patent marking is an acceptable alternative to physical marking. It can be useful in situations where all the patent information required to provide constructive notice cannot easily fit on the patented article or even its label, such as where there are multiple patents that apply to a given article or the article itself is very small. As the number of digits in patent numbers increase, this sort of difficulty increases. Virtual marking can also be helpful in situations where different patents are associated with different products but having multiple product-specific molds, printing proofs/templates, badges, labels, or packages is burdensome—a single mold, printing template/proof, badge, label, or package might be used listing a URL for a web page with patent association information for multiple products. Virtual marking can also separate some aspects of marking from the product manufacturing process, such as by minimizing the need to replace or modify expensive molds used to create a patent marking notice directly on molded articles as new patents issue.

Implementing virtual patent marking involves fixing notices on the patented articles themselves (or their labels/packaging) in a way that (indirectly) associates the patented article with the number(s) of the patent(s) via an Internet posting identified on the notice.[20] Such a virtual marking notice must use the word “patent” or the abbreviation “pat.” together with an address of a posting on the Internet (that is, a URL for a web page or comparable posting), accessible to the public without charge for accessing the address.[21] If the nature of the patented article means such a notice cannot be fixed to the patented article itself, the virtual marking notice (indicating “patent” or “pat.” together with a URL) can instead be placed on a label fixed either to the patented article or to a package containing one or more of the patented articles—just as with traditional physical marking as explained above.[22] This is an alternate approach is appropriate if (and only if) there is a legitimate reason the marking notice cannot be directly fixed to the article. But this alternative is not always and automatically permissible if the article itself can carry a notice. If a virtual marking notice is used on packaging or a label, the patentee should be prepared to articulate a reason why a virtual marking notice on the article itself was not practical. That reason should involve more than convenience and/or subjective preference, and should be established or apparent at the time marking decisions are made.

An example of a proper virtual patent marking notice fixed to a patented article or its label is the following:

Pat. example.com/patents

Further, the following is a photo of a reusable bottle cap product with a virtual patent marking notice etched into the metal of the product itself. It says “PAT” followed by a URL to a web page, although only a portion of the URL is visible in the photo due to the shape of the product. This type of virtual marking notice fixed directly on a patented article is acceptable under U.S. law.

The following is a photo of a powdered laundry detergent box with a virtual patent marking notice printed on the exterior of the package. It says “Patents/Patentes:” followed by a URL to a web page, with the word “patents” followed by the Spanish translation “patentes”. This type of virtual marking notice fixed on a patented product’s package would be acceptable under U.S. law, because the powdered form of the detergent does not allow the marking notice to be fixed directly to the powder. The presence of a Spanish translation of the word “patents” between the word “patents” and the URL is probably acceptable, because it is clear that it is a translation and that the English word “patents” indicates the significance of the URL that follows.

![photo of powdered laundry detergent box with "Patents/Patentes: www.[].com/patents" virtual patent marking notice printed on the exterior of the package](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/virtualpatentmarkingpackage-1024x162.jpg)

The main feature of virtual marking—the part that makes it “virtual”—is that the information associating the patented article with the number(s) of the patent(s) that cover it appears on a freely-accessible web page rather than directly on the article or its label or package. There is still a requirement for a notice on the patented product or its label or package. A marking web page, alone, is insufficient unless there is also a proper notice on the patented product or its label or package to direct people to that web page’s address.[23] Moreover, a virtual marking notice on a product or its package is insufficient without an acceptable posting accessible from the identified Internet address.

The difference between physical and virtual marking really involves the manner of conveying the required association between the patent number(s) and the patented article. With traditional physical patent marking, the association is implicit in terms of which patent numbers are including in or omitted from a notice fixed to a particular product or its label or package. In virtual marking, the notice fixed to the product or its label or package merely directs the public to a web page but the web page must further provide an association between given patent(s) and the specific product(s) that practice those patent(s).

Courts have said that virtual patent marking does not allow a patentee to avoid the traditional burden of determining which patent(s) apply to specific products and indicating that patent-to-product association.[24] The patentee cannot shift that burden to the public.[25] Any web page that fails to create the required “association” between specific patent(s) and patented article(s) means that such attempted virtual marking is ineffective and fails to provide constructive notice—unless and until the virtual marking web page is revised to cure the lack of patent-to-product association defect(s).

![Redacted screenshot of virtual patent marking web page that reads:"LEGALPATENTS ARCHIVEPatents ArchiveIn accordance with Section 287(a) of Title 35 of the United States Code, the reader is hereby placed on notice of [] Golf Company's rights in the United States Patents listed on this site and associated with the following products.Woods:

[] 815 Driver

- 8,[],534

- 8,[],911

- 8,[],294

- D[],156

- D[],388[] 816 Driver

- D[],997"](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/virtualmarkingpageredacted.jpg)

In the example above, a virtual patent marking web page includes some introductory text that reads, “In accordance with Section 287(a) of Title 35 of the United States Code, the reader is hereby placed on notice of [] Golf Company’s rights in the United States Patents listed on this site and associated with the following products.” That introduction is followed by identifications of specific products (by model name) and bulleted lists of associated patents. The web page is accessible to the public without charge. This format of a virtual patent marking web page, which provides specific patent-to-product associations, is acceptable under U.S. law. The use of introductory text is not required but may be helpful to contextualize the patent-to-product identifications. Of course, a proper notice listing the address (URL) of the depicted web page would also have to be fixed to products in order to establish constructive notice.

Minimum Requirements for Virtual Marking Web Pages

Virtual marking is relatively new compared to physical marking. Only a few courts have addressed questions about what does or does not constitute sufficient virtual marking, and those few decisions are not necessarily definitive. But what courts have said to date is that a virtual patent marking web page must make an association between specific product(s) and specific patent(s) in order to be effective. The virtual marking web page must be as specific and detailed as was required with physical marking.[26]

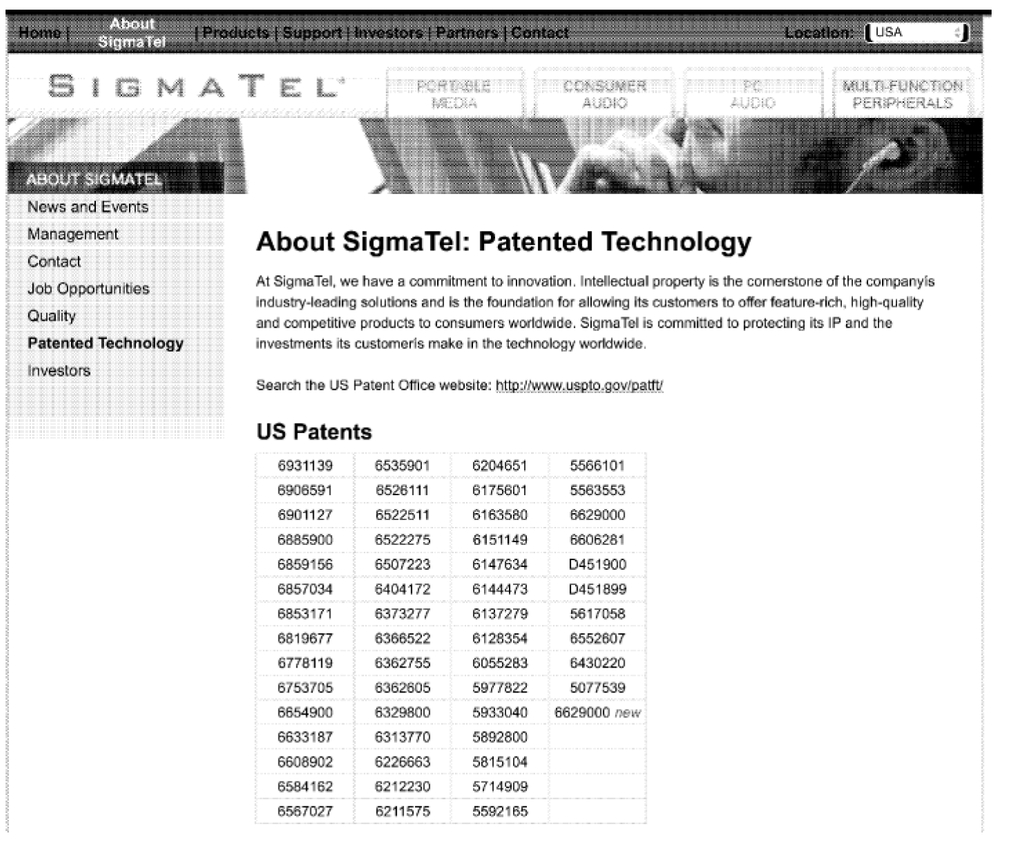

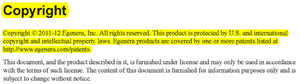

Courts have repeatedly emphasized that a virtual marking web page cannot create a “research project” for the public that requires visitors to investigate and determine on their own which patent(s) are associated with which patented article(s).[27] Merely listing all patents owned by the patentee without further identifying specific patent-to-product associations is insufficient, even if that list involves only a relatively small number of patents and is accompanied by a statement that “one or more” patents in a list of patents applies to given product(s).[28] Also, associating patent(s) with broad categories of products rather than specific patented products has been found insufficient.[29] One court has even said that a web page linking to documents about legal proceedings that visitors would have to read and interpret to determine which patent(s) cover which product(s) is still an impermissible “research project”.[30] In reaching these decisions, courts have noted prohibitions on false patent marking,[31] a topic discussed below.

Courts have not yet definitively interpreted whether “an address of a posting on the Internet, accessible to the public without charge for accessing the address, that associates the patented article with the number of the patent” requires a URL that directs to a specific web page with virtual patent marking information or whether a URL for a general home page of a web site is sufficient, where visitors must search for a different page on that site containing virtual marking information. But the plain language of the statute suggests that the marking notice on the article must indicate the relevant “posting” and not merely a collection of postings that are not all relevant or some intermediate posting where the address of the real posting of virtual marking information is findable. Cases that prohibit a “research project” also support the notion that requiring visitors to search out the relevant information on a different web page than the one at the URL indicated on the patented article impermissibly shifts the patentee’s burden to the public. It is recommended that the notice list the URL for the specific web page with virtual marking information—considerations regarding redirects and menus are taken up below.

A virtual marking web page also needs to be technologically functional. One court found that virtual marking was substantially continuous despite unavailability of the web page over a three-month period during a web site update.[32] But the fact that the court had to rule on that issue at all means that patentees should minimize the length of downtime due to computer hardware maintenance, cosmetic redesigns, and the like.

Some Practical Considerations for Virtual Marking

Virtual marking implicitly requires that reliable records be kept and retained to prove that relevant information actually appeared on the Internet at particular times—in addition to evidence that the patented articles bore a notice. If a patent is enforced and the patentee wishes to rely on constructive notice provided by virtual marking, there will be a need to provide evidence that the Internet address (URL) in the notice fixed to the patented article or its label was substantially continuously “accessible to the public without charge for accessing the address” and that the content of that web page “associate[d] the patented article with the number of the patent”. That evidence must be correlated with provable date(s) of constructive notice from which infringement damages run.

One way to provide such evidence is testimony from information technology (IT) staff and/or a webmaster knowledgeable about the creation of the virtual marking web page and any modifications or changes to it over time. But depending on how a web site is set up and managed, logs or other records of changes might not be automatically kept, and IT staff and webmasters might not recall the history of any given page. These concerns are significant when the page appears on a large and complex web site, where there is a large team of IT/webmaster personnel with diffuse responsibilities, or when there is significant personnel turnover over the enforcement period of a patent (potentially more than 20 years).

Another—and more consistently reliable—way to provide evidence to support virtual patent marking is to create a verifiable record of the virtual marking web page. This may include keeping a verifiable written log of changes to a virtual marking web page, when they were made, and who made the changes. If such records are kept in the ordinary course of business, they may fall in an exception to hearsay and be self-authenticating under federal evidentiary rules applied by courts,[33] which may avoid the need to produce a witness to authenticate them. Similarly, archived copies of the virtual patent marking web page can be periodically created. There are third-party digital evidence authentication services that could be used for this purpose. For instance, the Internet Archive’s “Wayback Machine” (web.archive.org) is a free, open-access archive service that can be used to create a verifiable archive. But the ability of some tools to archive a given web page will depend on web site settings and permissions allowing “bots” to crawl the site. In any event, under this approach, the virtual marking web page should be affirmatively submitted to a desired archive provider when first created and following each and every substantive modification.

Make sure that the patent marking web page URL remains static and unchanged (i.e., link permanence is maintained and link rot avoided), that the web page at that URL remains substantially continuously available and functional (i.e., a hosting web server is operational and the web page code is reasonably free of bugs or browser compatibility problems), and that the notice accurately lists the web page URL (i.e., patented articles carry an accurate virtual marking notice). Typos in the URL carried on the patented article or its label are potentially problematic here. Also, notices that list a dead or defunct URL will not satisfy marking requirements. This could arise, for instance, from prolonged web server malfunctions or the like. Issues could also arise if the URL for the actual web page is changed but labels on patented products that have already been distributed cannot be altered. Loss of rights to the domain name that forms part of the URL in virtual marking notice in previously-distributed products could be a problem, such as if the link involves a domain name registration that is cancelled or transferred due to cybersquatting. Mergers and acquisitions or the sale of a patent might also make it difficult to maintain a static URL for virtual marking purposes. So, before implementing virtual marking, it is recommended to confirm that the relevant URL used in a marking notice can reasonably be expected to remain static for the enforceable life of the relevant patents (which is up to six years after the expiration of the last of those patent(s)). In corporate mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and patent acquisition scenarios, and corresponding due diligence activities, it may be desirable to secure access to existing virtual marking URLs, or at least to provide for a redirect from that URL.

It is not necessary for the URL of the virtual marking web page to include any particular domain name. It is not necessary that the domain in the URL reference the patentee’s name or trademark, for instance. It is acceptable for the URL to direct to a page at a third-party provider’s web site, or that of a licensor. Moreover, the URL listed in a marking notice could even utilize a publicly-accessible server Internet Protocol (IP) address instead of a domain name as such (for instance, “http://000.000.0.0/patents.html”).

However, consider whether the URL of the virtual marking web page as fixed to articles is for a domain that may not be readily recognized as an Internet address, such as an IP address without a domain name or using an uncommon top-level domain. If the public is unlikely to recognize such an address as an Internet address in a shortened form, make sure that a full address including “http://” and/or “www.” is included. Though for URLs at familiar top-level domains like “.com”, it seems adequate to list a shortened address so long as typical web browsers will direct visitors to the site by typing only the shortened address.

While a machine-scannable QR code or the like may seem helpful for virtual marking, use of such a scannable but not human-readable code on the patented article or its label may not alone satisfy the “address of a posting on the Internet” requirement for virtual marking. Courts have not yet addressed this question. If used at all, any QR code or the like should appear in addition to an Internet address (URL) in alphanumeric characters, plus the required “patent” or “pat.” indication.

It is recommended to keep the virtual marking page as simple as possible. Use of complex user interfaces may present problems. If the complexity of a web page, such as requiring the use of highly uncommon or unreliable web browser plug-ins, raises questions about whether it is really “accessible to the public”, then it may not provide constructive notice. Use of menus on a virtual marking landing page and/or redirects (such as URL mapping from a “clean” or “friendly” URL) may or may not satisfy the constructive notice requirements. The sufficiency may depend on the specific circumstances and context. On the one hand, the statue refers to “an address of a posting on the Internet . . .”, which does not explicitly prohibit interactive features or redirects. After all, the Internet Domain Name System (DNS) relies on a variety of pointers to relevant servers all the time, as do commonplace site mirroring practices. An effective browser redirect or simple menu to select a particular product would seem to reasonably provide public notice without any meaningful restriction, and therefore seems acceptable for providing constructive notice. On the other hand, redirects or complex menus that mean the “posting on the Internet” is not actually at the “address” provided in the notice fixed to the patented article or its label might not satisfy constructive notice requirements under a strictly literal reading. And complicated or non-intuitive menus may create an impermissible “research project” for the public. Courts have not definitively resolved such issues. Though effective redirects seem unlikely to raise concern, though the use of convoluted menus might (depending on context). It generally recommended to use a relatively simple implementation, and possibly the least complex technical implementation that is feasible. Consider separate virtual patent marking web pages for different products or categories of products rather than a single page, if doing so will avoid the need for potentially problematic complexity.

Also consider the accessibility of the format in which virtual marking information is displayed or rendered on a web page from a disability access perspective. For instance, displaying a graphical image without alt text information, conveying information based solely on color-coding, or complex “flyout” displays tied to precise cursor hovering actions may not be able to be conveyed by a braille or audio reader for a visually-impaired site visitor. It is a best practice to follow common accessible design standards for the formatting and presentation of virtual patent marking information. Such considerations also extend to any menus that must be navigated to access specific patent-to-product association information. Accessibility requirements from other areas of federal law, or from state or foreign jurisdictions, may or may not apply to any given virtual patent marking web page. However, the patent laws do not directly impose any minimum accessibility requirements for differently-abled visitors.

Product photos or drawings could be utilized on a virtual marking web page to aid in the association of particular patents and particular products. However, such photos or drawings should ideally be used only in addition to textual product identifiers. A photo or drawing alone might still be considered to present an impermissible research project if visitors need to decipher which product(s) it depicts. It is also recommended to include alt text metadata with any product photos or drawings used on the virtual marking page.

Use of visitor tracking features on virtual patent marking web pages presents a few issues that suggest caution. Patent owners might wish to verify whether the page has been visited, and who visited, through tracking mechanisms (“cookies”, “free” login requirements, etc.). The thought may be that this could provide evidence that an infringer visited the page. However, constructive notice for the accrual of damages does not require that the infringer actually saw a patent marking notice or actually knew about the asserted patent(s). So that sort of evidence is not necessary to establish constructive notice, nor is it sufficient to establish actual notice—although it might be usable to establish willful infringement. The U.S. marking statute says that the virtual marking web page must be “accessible to the public without charge for accessing the address.” Whether or not visitor tracking (with or without a predetermined “conversion value”) effectively constitutes a non-monetary access “charge” has not yet been addressed or settled by courts. Websites that require affirmative visitor consent to tracking or to obtain login credential in order to view a virtual marking page or might especially raise such concerns and therefore are not recommended. Giving visitors the option to reject all tracking would seem to avoid these concerns, provided that such opt-out requests are actually honored.

Additionally, the retention of visitor data for online tracking (via “cookies”, etc.) is subject to increasing scrutiny and regulation. These include privacy concerns. Use of visitor tracking functionality and associated data retention may require analysis for legality under applicable laws other than the U.S. patent laws—federal and state law(s) or even possibly foreign law(s) like GDPR in Europe and PIPEDA in Canada. Consider various data protection best practices that may apply to the virtual patent marking context.

Pre-Grant Marking

“Patent Pending”

The statutory patent marking requirements discussed above apply only to granted/issued patents. There is no requirement to mark products as “patent pending” or in any other way while a patent application is pending. However, it is permitted and recommended to mark products as “Patent Pending” or “Pat. Pending” or “Patent applied for” when a U.S. patent application has been filed but no patent granted yet. This serves as a “copy at your own risk” warning.

Sometimes there will be one or more granted patents plus one or more pending patent applications that apply to a given product. It is possible to list all patents granted to date in a marking notice and further indicate “other patents pending” or the like. Sometimes notices of this sort may indicate that foreign patents exist or are pending as well. This sort of information is extraneous to U.S. patent marking requirements but might be helpful, so long as it is accurate. But there is no adverse consequence to a patentee for having sold products with no marking or only “patent pending” marking before a patent is granted.

![Redacted photo of bird feeder product package (box) with the patent marking notice "Protected by U.S. Patents 6,[],707 and 6,[],384 and Patents Pending" printed on it.](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/patentmarkingbirdfeederboxredacted-1024x152.jpg)

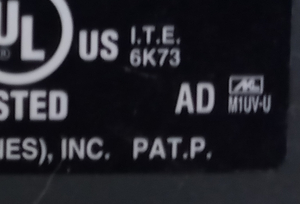

In the following example of a combination printer/scanner product, a notice reading “PAT.P.” is fixed directly on the product with a permanently-adhered sticker. This notice is ambiguous and unclear. Moreover, depending on the context and intent, this notice might raise allegations of false marking. While “PAT.” is an accepted abbreviation of the word “patent”, the abbreviation “P.” does not have a specific meaning in the patent marking context. It might refer to “pending” or it might be interpreted as “protected”, “properly”, “product”, “publication”, “possible”, etc. For pre-grant marking, it is recommended to use wording like “pat. pending” or “pat. applied for” without abbreviating “pending” or “applied for”. At a minimum, abbreviate the word “pending” only as “pend.”

It is not necessary to recall or modify patent pending markings on products that were sold before an applicable patent issued. And, similarly, if a patent application is later abandoned without a patent issuing there would be no need to recall products from end users that were already sold with a patent pending notice. But there may be difficult decisions to be made if a considerable inventory of articles is being held at the time an applicable patent issues, given that the subsequent sale of those unmarked products from inventory will generally trigger the limit on damages for distributing unmarked products. Marking notices would need to be added to inventoried products or their labels/packages in such a scenario in order to satisfy marking requirements. Similarly, if a pending patent application is abandoned and a significant inventory of products (or their labels/packages) are in inventory, such notices may need to be removed to avoid false marking if the seller knows that leaving the notice in place will deceive the public.

For products sold internationally, be aware of potential different treatment of “patent pending” markings in other jurisdictions. In some countries, use of English-language patent pending notices may be treated as false marking if a patent has not actually been granted, despite such a view being contrary to the ordinary meaning of such notice language in the U.S.

Publication Number Marking

Marking a pre-grant patent publication number could possibly help support later damages recovery for infringement, in theory. One anomaly of U.S. patent infringement damages law is that under certain circumstances reasonable royalty damages can accrue before a patent is granted.[34] These are referred to as “provisional rights”.[35] They are available only if the invention as claimed in the granted patent is “substantially identical” to the invention as claimed in a published version of the underlying patent application and suit is brought within six years of grant of the patent.[36] An infringer who “had actual notice of the published patent application” can be liable for pre-grant “provisional rights” reasonable royalty damages in addition to traditional infringement damages.[37]

Provisional rights for pre-grant reasonable royalty damages are not subject to any marking requirement. There is no statutory requirement that an article later patented be marked as “patent pending” or the like before a patent is granted in order to obtain reasonable royalty provisional rights damages—provided all other requirements are satisfied. Courts have interpreted “actual notice of the published patent application” for pre-grant provisional rights to be based only on the infringer’s actual knowledge (i.e., state of mind), without requiring affirmative action by the applicant or eventual patentee.[38]

However, because “actual knowledge” of a published patent application may give rise to provisional rights damages, marking the patent application publication number on articles subject to a pending patent application could potentially support a claim of such knowledge by the infringer—provided there is evidence that the infringer actually saw that notice. However, there is no constructive notice doctrine for publication number marking. But, at the least, marking a publication number could support an inference of actual knowledge if there is evidence that the infringer saw a marked product. This may be an incentive to mark a published patent application number on relevant goods, beyond merely a generic “patent pending” notice.

But provisional rights are rarely available in typical real-world scenarios. Opportunities to assert them rarely materialize. So this sort of enhanced pre-grant publication number marking may be of marginal practical value. The burden of doing this may outweigh the potential benefit. Certainly, this approach will be less effective than affirmatively communicating with a potential infringer to provide knowledge of a published patent application via a letter or the like, when possible.

False Patent Marking Prohibited

An important related concept is false patent marking. Under § 292 of the U.S. patent laws, false marking generally involves marking products as patented when they are not, or marking products as “patent pending” when no patent application has been filed, with an intent to deceive. Use of words like “patent” or “patentee” to advertise unpatented articles with intent to deceive the public is also prohibited. False marking also applies to certain acts of intentional counterfeiting. Penalties apply in the U.S. to false marking with requisite intent.[39] However, the U.S. patent laws now expressly say that the marking of a product with matter relating to a patent that covered that product but has expired is not a false marking violation (historically this did constitute false marking but no longer)—yet possibly still leaving in place penalties for falsely advertising a product as being patented when after patent protection has expired.[40] Also, there is no liability for honest mistakes about whether or not a patent applies.[41] A reasonable belief that the articles were properly marked (i.e., covered by the indicated patent) avoids false marking liability.[42]

Currently, either the U.S. Government or “a person who has suffered a competitive injury as a result of a violation” can sue for false marking.[43] Government action fines are “not more than $500 per offense” and are assessed on a per-article basis.[44] Private actions are “for recovery of damages adequate to compensate for the injury[,]” meaning there is no fixed minimum or maximum on potential damages for a competitive injury suit by a competitor or certain potential competitors.[45]

False marking is prohibited for a number of reasons. It misleads the public into believing that a patentee controls the article in question (as well as like articles), externalizes the risk of error in that determination (shifting it to the public from the manufacturer or seller of the article), and increases the cost to the public of ascertaining whether a patentee in fact controls the intellectual property embodied in an article.[46]

It is important to only use patent marking where there is a reasonable basis to believe that the product is covered by the indicated patent(s) (or by a pending patent application if “patent pending” is marked). Patents that do not apply to a given product must not be marked on it. In the virtual marking context, patent-to-product associations must be specific enough to avoid false marking. Imprecise, blanket statements on virtual marking web pages implicating multiple patents and multiple products might give rise to false marking if done for purposes of deceiving the public about which patents, if any, apply to particular products.

Conditional marking, such as marking products with “may be covered by” patent notices or indicating that “one or more” listed patents apply, may constitute false marking.[47] Some courts have said that the mere fact that one applicable patent is listed among others that are inapplicable is insufficient to dismiss a claim of false marking.[48] Often, these evaluations are ultimately less about falsity but instead turn on whether the patentee had intent to deceive the public by using conditional language.[49] Courts have not been entirely clear or consistent about what could plausibly constitute intent to deceive. Yet acting recklessly rather than innocently or negligently, taking a self-serving (if not outright bad-faith) position that the public would allegedly never be deceived by conditional language, or consciously choosing to place profitability concerns above compliance with false marking prohibitions should all qualify as an intent to deceive. As a best practice, it is recommended to avoid conditional marking language.

![Redacted photo of conditional patent marking notice on a product that reads "ONE OR MORE OF THE FOLLOWING U.S. PATENTS APPLY: RE[]726; D[],731; D[].993; D[],524; 5,[],43."](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/patentmarkingconditional-1024x204.jpg)

In the example above, a “conditional” patent marking notice is fixed directly to a product next to a model number on a permanently-affixed sticker. The notice reads (with patent numbers partially redacted), “ONE OR MORE OF THE FOLLOWING U.S. PATENTS APPLY: RE[]726; D[],731; D[].993; D[],524; 5,[],43.” The language “one or more of the following U.S. patents apply” is conditional language. This notice could constitute false marking if any of the listed patents do not have a claim that covers the product and the notice is used with intent to deceive the public.

Falsely listing an irrelevant patent number on an unpatented product is not the only possible ground for false marking liability. Falsely marking or otherwise advertising something is “patented” without giving a patent number,[50] or potentially even indicating alphanumeric characters that look like a patent number without the word “patent” or “pat.”, are prohibited as well, if done with an intent to deceive. Notices such as “patented internationally” or “patented worldwide” may or may not constitute false marking, depending on the context and the intent to deceive when providing such a notice. For one, setting aside certain foreign patents that are regionally enforceable only outside the USA, there is no such thing as an “international”, “global”, or “worldwide” patent. But, also, the lack of an applicable U.S. patent may be especially important for false marking liability if “worldwide”, “globally”, “international”, or similar terms are used with deceptive intent, or if the word “patent” alone is used in the U.S. with intent to deceived where only foreign patent rights exist.[51]

It is recommended to avoid marking products with any “patented” language that is confusing, geographically vague, or potentially misleading with respect to that product’s patent status in the USA. Moreover, for products that are sold internationally, patent markings and advertisements should delineate the specific jurisdiction(s) where they are patented or the products, their labels or packages, and their advertisements should be modified by jurisdiction.

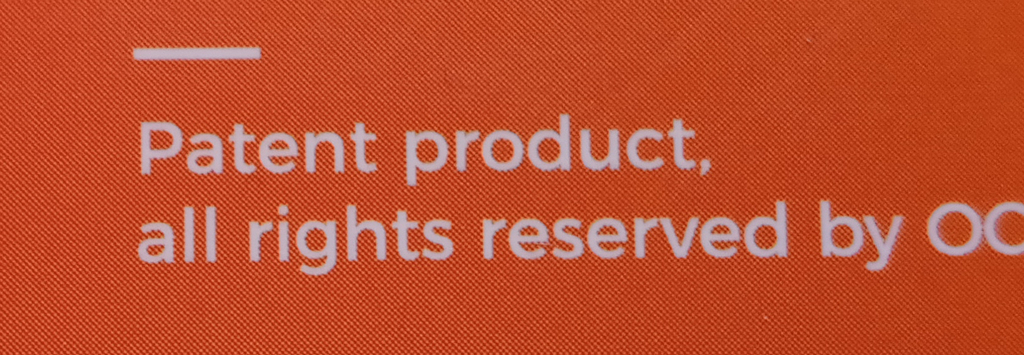

In the following example photo, a battery-powered electric handwarmer product has “Patent product” marked on its package. Because no U.S. patent number is listed, such a notice is insufficient to provide constructive notice under U.S. patent laws to accrue damages, as discussed above. But a notice like this could potentially still give rise to false patent marking liability if used in connection with a product that is unpatented in the U.S. with intent to deceive the public.

Courts have not definitively ruled on the effect, for false marking analyses, of continuing to mark products with a patent that has been invalidated, cancelled, or disclaimed (completely or in relevant part), or how opportunities to appeal an adverse ruling may alter the analysis.[52] Suffice it to say, the § 292(c) exception for expired patents does not apply. In such situations, it may be possible to explicitly indicate an adverse ruling next to the patent number (something easiest with virtual marking). Though courts have not explicitly ruled on the sufficiency of such a disclaimer-like indication, and considerations like those discussed for conditional marking may arise. Of course, ceasing to mark the invalidated or cancelled patent number would completely avoid allegations of false marking. In situations involving partial invalidation or cancellation, more nuanced review is appropriate. Bear in mind that partial invalidity or cancellation may affect some but not all patent-to-product associations and therefore may require very context-specific patent marking updates.

To Mark or Not to Mark?

There is no absolute requirement for patentees to mark patented articles. Marking is optional. A failure to mark only limits one of two ways to recover pre-suit damages. In the end, there is no single right or wrong answer to the question of whether a patentee should mark or not.

In fact, many patentees consciously make the decision not to mark. This may simply be because the burdens are considered too high, from a business or engineering perspective. For instance, it may be too burdensome to mark a product sold internationally but only in limited quantities in the U.S. Or the patentee may feel that the likelihood of a contentious infringement lawsuit where constructive notice matters is too remote. In some industries, competitors may be generally aware of the patents they each hold and tend to honor them, and those sorts of industry norms may satisfy some patentees without marking. Moreover, it may be easier in some circumstances to send letters to place infringers on actual notice than to mark all patented articles. And for “paper” patents that are not being actively practiced, marking is a moot point.

Triggering actual notice with a letter or other affirmative communication will give rise to the possibility of a declaratory judgment action, in which the accused infringer files suit, whereas passively marking products would not.[53] A declaratory judgment action might involve forum-shopping by the accused infringer, or draw the patentee into a lawsuit more quickly than desired. That is simply a consequence of relying on actual notice rather than constructive notice through marking.

Moreover, in many situations, infringement might begin well before the patentee becomes aware of it. Thus, a significant amount of infringement may occur before a letter can be sent to communicate a charge of infringement or a lawsuit initiated. In those situations, the potential damages that arise before the patentee can affirmatively act may be significant. That is perhaps the best reason to mark. Patent marking is a way to preserve the ability to recover all or nearly all damages from infringement in the face of imperfect knowledge of competitor activities.

Implementing a Marking Program

Patentees who do decide to mark should create a program to ensure that marking is legally sufficient.

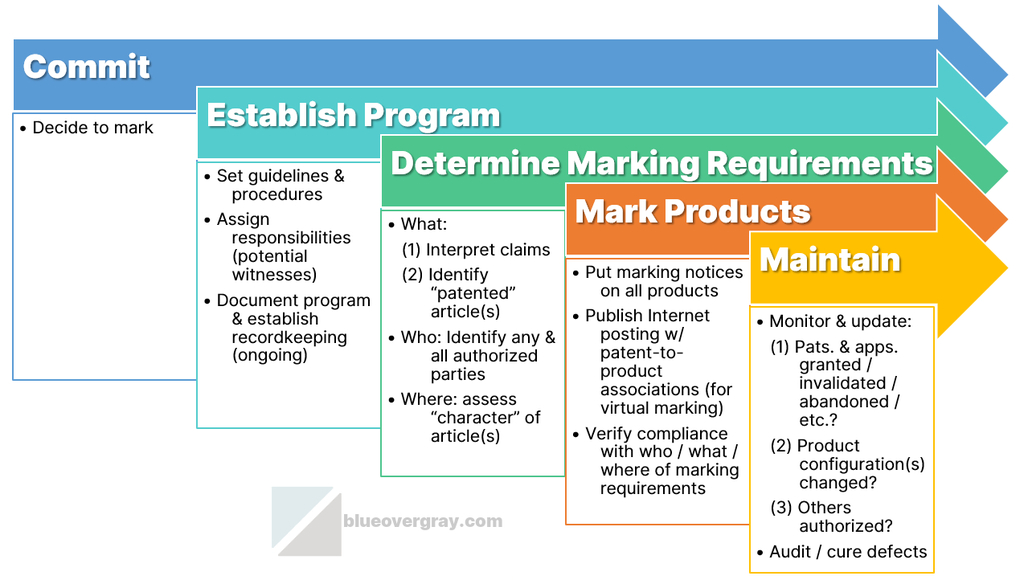

Steps in implementing patent marking may include:

- Making a commitment to mark that includes allocating time and resources;

- Establishing program guidelines/procedures together with assignment of responsibilities and the beginning of ongoing marking documentation and record-keeping that can be used in court as evidence (including having knowledgeable person(s) available as witnesses), noting that such records should be maintained for the entire enforceable life of a given patent, which can be up to six years after expiration;

- Determining marking requirements by (3a) interpreting patent claims and identifying all patented articles that fall under at least one claim (as properly interpreted), (3b) identifying any and all authorized parties also subject to marking requirements (such as express or implied licensees, etc.), and (3c) assessing if the “character” of the patent article(s) means that patent marks cannot be placed directly on the patented articles;

- Implementing marking by fixing legally-compliant notices on all patented articles (or on their labels/packaging if and only if necessary because of the character of the article) and providing a legally-compliant patent-to-product association posting on the Internet if using virtual marking, and by verifying that all legal requirements as to the form and placement of patent marks (and any virtual marking Internet posting) are consistently and continuously met, including by all authorized parties; and

- Maintaining marking efforts by monitoring and making updates to marking implementation (including to associated records/documentation) due to changes in patent and patent application status such as new patent grants, abandonment, expiration, invalidation, etc. (including deciding what to do about any unmarked undistributed inventory at the time of a relevant new patent grant), changes in product configuration(s) that affect what is or is not a patented article, and/or changes in authorizations to others under the patent(s), and further consider undertaking periodic audits to ensure compliance, and finally by taking steps to cure any defective marking as quickly as possible.

The implementation of proper marking may require planning, coordination, and ongoing effort. Those challenges increase the more patents and products are involved. But carrying out a patent marking program helps inform the public that given products are patent and helps ensure that the patentee can obtain full recovery for infringement.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.

Endnotes:

[1] Am. Med. Sys., Inc. v. Med. Eng’g Corp., 6 F.3d 1523, 1536 (Fed. Cir. 1993) cert. denied 511 U.S. 1070 (1994); see also Nike, Inc. v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 138 F.3d 1437, 1440,1446 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (a failure to mark also limits recovery of an infringers profits under 35 U.S.C. § 289 for design patents); 35 U.S.C. § 286 (back damages are only available for the period six years prior to commencing a lawsuit or raising a counterclaim).

[2] Bonito Boats, Inc. v. Thunder Craft Boats, Inc., 489 U.S. 141, 162 (1989) (“The public may rely upon the lack of notice”); Wine Ry. Appliance Co. v. Enter. Ry. Equip. Co., 297 U.S. 387, 397 (1936)(statutory marking requirement is “for the information of the public” and provides “protection against deception by unmarked patented articles”); Rembrandt Wireless Techs., LP v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Ltd., 853 F.3d 1370, 1383 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (“The marking statute protects the public’s ability to exploit an unmarked product’s features without liability for damages until a patentee provides either constructive notice through marking or actual notice.”).

[3] Nike, 138 F.3d at 1443; cf. Lans v. Digital Equip. Corp., 252 F.3d 1320, 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (“knowledge of the patentee’s identity” through notice requirements “facilitates avoidance of infringement with design changes, negotiations for licenses, and even early resolution of rights”).

[4] Amsted Indus. Inc. v. Buckeye Steel Castings Co., 24 F.3d 178, 187 (Fed. Cir. 1994); Lans, 252 F.3d at 1324-28 (notice must be from patentee and not a different party; notice letters sent by sole inventor that inaccurately asserted personal ownership following assignment of the patent to his solely-owned and managed corporate entity for tax reasons was inadequate to provide actual notice of infringement because not an affirmative act by the patentee).

[5] 35 U.S.C. § 287(a).

[6] Id.

[7] Nike, 138 F.3d at 1446 (“In determining whether the patentee marked its products sufficiently to comply with the constructive notice requirement, the focus is not on what the infringer actually knew, but on whether the patentee’s actions were sufficient, in the circumstances, to provide notice in rem.” “In order to satisfy the constructive notice provision of the marking statute, [the patentee] must have shown that substantially all of the [patented products] being distributed were marked, and that once marking was begun, the marking was substantially consistent and continuous.”); see also, e.g., Funai Elec. Co v. Daewoo Elecs. Corp., 616 F.3d 1357, 1374-75 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (evidence that 88-91% of patented products were marked supported verdict that such marking was substantially consistent and continuous).

[8] Am. Med. Sys., 6 F.3d at 1538; Arctic Cat, Inc. v. Bombardier Recreational Prods., Inc., 950 F.3d 860, 861,864-66 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (merely ceasing sales of unmarked products does not cure a failure to mark and back damages are precluded until sales resume with proper marking or actual notice is provided); Rembrandt Wireless Techs., 853 F.3d at 1382-84 (statutory disclaimer of selected claim made eight days after commencement of litigation “cannot serve to retroactively dissolve the § 287(a) marking requirement for a patentee to collect pre-notice damages.”); see also, e.g., NXP USA, Inc. v. Impinj, Inc., No. 2:20-CV-01503 (W.D. Wash. May 4, 2023) (failure to mark does not preclude pre-suit damages for a period before any such marking obligation arose, even though later sale of unmarked products triggers limitation on pre-suit damages recovery) accord Clancy Sys. Int’l., Inc. v. Symbol Techs., Inc., 953 F. Supp. 1170, 1174 (D. Col. 1997).

[9] Tex. Digital Sys., Inc. v. Telegenix, Inc., 308 F.3d 1193, 1219-20 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (“The recovery of damages is not limited where there is no failure to mark, i.e., where the proper patent notice appears on products or where there are no products to mark.”) (citing Wine, 297 U.S. at 398).

[10] Bandag, Inc. v. Gerrard Tire Co., 704 F.2d 1578, 1581 (Fed. Cir. 1983); accord ActiveVideo Networks, Inc. v. Verizon Commc’ns, Inc., 694 F.3d 1312, 1334-35 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (“we reaffirm the bright-line easy to enforce rule: if the patent is directed only to method claims, marking is not required”).

[11] Crown Packaging Tech., Inc. v. Rexam Beverage Can Co., 559 F.3d 1308, 1316-17 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (while assertion of both method and apparatus claims triggers the obligation to mark under 35 U.S.C. § 287(a), the assertion of only the method claims of a patent containing both method and apparatus claims does not) (citing Am. Med. Sys., 6 F.3d at 1538-39 and Hanson v. Alpine Valley Ski Area, Inc., 718 F.2d 1075, (Fed. Cir. 1983)); see also Packet Intelligence LLC v. NetScout Sys., Inc., 965 F.3d 1299, 1313-15 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (evidence of infringing use of claimed method is required to support back damages award; lack of evidence of pre-notice infringing use of patented methods resulted in back damages award being overturned, where patentee failed to establish marking for additional patent’s asserted apparatus claims and pre-notice sales of infringing articles were the only evidence supporting patentee’s back damages theory).

[12] 35 U.S.C. § 287(a).

[13] Amsted Indus., 24 F.3d at 185 (“A licensee who makes or sells a patented article does so ‘for or under’ the patentee, thereby limiting the patentee’s damage recovery when the patented article is not marked.”) (citing Devices for Med., Inc. v. Boehl, 822 F.2d 1062, 1066 (Fed. Cir. 1987)); In re Yarn Processing Patent Validity Litigation, 602 F. Supp. 159, 169 (W.D. N. Car. 1984) (the marking requirement “applies to authorizations by patentee of other persons to make and sell patented articles regardless of the particular form these authorizations may take and regardless of whether the authorizations are ‘settlement agreements,’ ‘covenants not to sue’ or ‘licenses.’ ” (citation omitted)). This includes impliedly authorizing customers to make and sell the patented article, such as selling a part specifically for use in the patented combination while providing customers with installation drawings that instruct how to assemble the part, along with other components, according to the teachings of the patent. Amsted Indus., 24 F.3d at 185. In that situation, the Federal Circuit suggested (in dicta) that a marking such as “for use under U.S. X,XXX,XXX” or “licensed under U.S. X,XXX,XXX” could have been used. Id. Without explanation, that Federal Circuit-recommended notice did not include the word “patent” or the abbreviation “pat.” as mandated by the marking statute. Moreover, that Federal Circuit decision refers to impliedly licensed use (“There is no dispute that Amsted impliedly authorized its customers to make, use, and sell the patented article” (emphasis added)), and further emphasized the possibility of a “for use under” notice, without any discussion of how the marking statute expressly applies to “making, offering for sale, or selling” but on its face excludes mere “use” — although this might simply be careless wording because the facts of the case involved not mere use by an implied licensee but rather resale of components as part of the entire patented combination by implied licensee in which the patentee was “making and selling the [unmarked] Low Profile plate to [impliedly licensed] rail car builders for assembly into the [unmarked] patented combination” and specifically “provid[ing] its [impliedly licensed] customers with installation drawings which instruct how to assemble the center plate, along with other components, according to the teachings of the patent . . . .” Id. at 180 and 185. The Amsted case did not discuss possible false marking liability for marking a component that, in isolation, was not the subject of at least one patent claim. A better approach than the Amsted dicta would have been for the patentee selling the unpatented piece part with instructions about how to assemble it into the patented combination to have included a patent marking notice sticker or the like, and expressly required (as part of the instructions and/or as a binding contractual condition) that users install the sticker on the completed patented combination. In that way, the patented combination would be marked at the time it is made but the unpatented piece part would avoid claims of false marking. Yet the patentee must still make reasonable efforts to ensure compliance with marking by licensees, under either implied or express licenses.

[14] Maxwell v. J. Baker, Inc., 86 F.3d 1098, 1111-12 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (“with third parties unrelated to the patentee, it is often more difficult for a patentee to ensure compliance with the marking provisions. A ‘rule of reason’ approach is justified in such a case and substantial compliance may be found to satisfy the statute.” “When the failure to mark is caused by someone other than the patentee, the court may consider whether the patentee made reasonable efforts to ensure compliance with the marking requirements.”).

[15] Id.

[16] See Amsted Indus., 24 F.3d at 185 (patentee “could have sold its plates with a requirement that its purchaser-licensees mark the patented products ‘licensed under U.S. [Pat.] X,XXX,XXX.’ “); Arctic Cat, 950 F.3d at 861,864-65; Egenera, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., 547 F. Supp. 3d 112, 126-27 (D. Mass. 2021); In re Yarn Processing Patent Validity Litigation, 602 F. Supp. at 169; and note 13, supra (discussing “for use under” marking); see also Frolow v. Wilson Sporting Goods Co., 710 F.3d 1303, 1309 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (“The practice of marking a product with a patent number is a form of extrajudicial admission that the product falls within the patent claims” that is “not ‘binding,’ and ‘may be controverted or explained by the party’ that made the statement.” (citation omitted)).

[17] 35 U.S.C. § 287(a).

[18] Id.; see also, e.g., T.C. Weygandt Co. v. Van Emden, 40 F.2d 938, 940 (S.D.N.Y. 1930) (“marking must comply strictly with the statute in order to constitute notice to the world that the article marked is patented”).