Trademark applications are sometimes refused for a failure to function. What is failure to function, and what does a failure to function as a trademark refusal mean? This article addresses the relevant requirements for U.S. federal trademark registrations, how to respond to such a refusal, and introduces a few related concepts.

The Function of Trademarks

Trademarks (and service marks) are used to identify the source of goods and services. Put another way, the basic purpose of trademarks is allow consumers to tell apart goods (or services) originating from different sources. Take any commodity—like a car, pen, or frying pan. Branding these with a trademark allows consumers to understand which ones original from company A rather than company B. This allows consumers to rely on branding as an indication of quality, and to avoid counterfeits or fakes that may be of unreliable quality.

The U.S. federal trademark laws, often referred to as the Lanham Act, actually include explicit definitions of trademarks (and service marks). These definitions emphasize that trademarks are indicators of source that distinguish goods from those made or sold by others.

“The term ‘trademark’ includes any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof— (1) used by a person, or (2) [constructively used by filing an intent-to-use application], to identify and distinguish his or her goods, including a unique product, from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods, even if that source is unknown.”

15 U.S.C. § 1127

Context and Form of Use Matter

In order for something to actually function as an indicator of source (that is, as a trademark), it has to actually be used in that sort of way. That means context and the form of use matter. And these are things are considered from the standpoint of consumer perception.

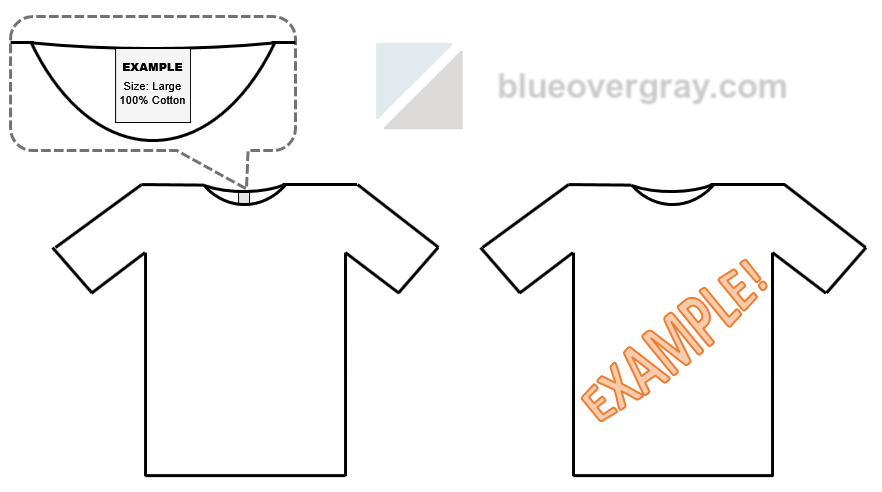

For instance, the prominence and precise location of a mark on goods or their packaging is important. A phrase buried in the “fine print” on an insert inside a package, but not visible to consumers when considering buying it does not function as a trademark. But a unique and distinctive logo that consistently appears on the front of the same package is likely to be recognized by consumers as a trademark that indicates the source of the goods.

A common issue is use of things on clothing. In some locations, these thing would be perceived as indicating the source. This includes distinctive branding on the tag inside shirt or attached label. Or sometimes there are conventions like having polo or tennis shirts branded with a logo that appears on a pocket or other location that is recognized by consumers as indicating the source of the shirt. But something on clothing that is merely ornamentation would generally not be perceived as an indication of source and thus fail to function as a trademark. This can arise, for instance, for merely background designs and shapes. These considerations are not limited to clothing either.

Content Matters

The nature of the content of an alleged trademark matters a lot too. Not every word, name, phrase, symbol or design, or combination of such things that appears on a product functions as a trademark. And mere intent that it function as a trademark is not enough in and of itself to make it a trademark. Merely informational matter fails to function as a mark to indicate source and thus is not registrable. That is because consumers would perceive such information matter as merely conveying general information about the goods or services or an informational message, and not as a means to identify and distinguish the applicant’s goods or services from those of others.

Common examples of things that fail to function as trademarks include: (a) general information about the goods or services that does no more than inform the public with reasonable accuracy what is being offered, and including highly laudatory claims of superiority (“best”, “greatest”, etc.); (b) a common phrase or message that would ordinarily be used in advertising or in the relevant industry, or that consumers are accustomed to seeing used in everyday speech by a variety of sources; or (c) something that primarily is or identifies the product itself rather than something that identifies the source of the product.

General Information

What does or does not constitute mere “general information” about goods/services is highly contextual. So it also relates to prominence and location of use, as discussed above; to function as a trademark such usage should stand out from merely information text in some way. Common examples of things that fail to function as trademarks are mere ornamentation, the title of a single work (as opposed to a series), or the name of an artist or author.

Mere model numbers, grade designations, and the like can also be merely information in nature. These depend on context too, including placement and prominence. For instance, the USPTO considers some model numbers and grade designations to be dual-purpose, serving as both a model or grade designation and a trademark. Similar considerations apply to so-called universal symbols, like the recycling symbol with arrows forming a triangle.

For instance, if a product package said “this end up”, most consumers would understand that as merely being an instruction for how to handle the package without damaging the goods inside, and not a trademark indicating the source of the goods. That phrase does not describe any quality or characteristic of the goods inside. Even so, consumers would still not see it as branding. The same could be said for many types of warning labels, address indications, prices, and all sorts of other information that accompanies the sale of goods and services.

In a notable case, two designations for crabmeat (shown below), each containing both stylized wording and graphical design elements, were each refused registration for failure to function. While sometimes the addition of stylization and/or graphical elements can provide sufficient distinctiveness to otherwise non-distinctive wording, those non-textual elements were insufficient here.

The wording was found to be merely informational terminology commonly used in the relevant trade/industry to denote the purity, quality, ingredients, and, for one of them, also the geographic origin. The minimally stylized font created no distinct commercial impression, nor did a simple geometric (circle) shape, which consumers would perceive as a background design or carrier to enclosed wording rather than as a separable design element with trademark significance. The image of a crab was also insufficiently distinctive because it was similar to, or reinforcement of, the meaning of the accompanying wording, and simply informed prospective consumers that the associated product is crabmeat.

Sometimes this relates to descriptiveness too. In one example case, THE BEST BEER IN AMERICA was found to be so highly laudatory and descriptive of the qualities of its product—beer—that the slogan did not and could not function as a trademark. Situations like this involve self-lauditory terms that are normally considered descriptive, and typically involve slogans. But to give one user exclusive rights would be ridiculous. In this sense, general information is incapable of acquiring secondary meaning and thus incapable of functioning as a trademark. This makes sense because all competitors want and deserve the ability to use common lauditory terms and slogans and consumers are unlikely to see them as source-indicators.

But this goes beyond self-lauditory terms. In another case, LITE was incapable of functioning as a trademark for vegetable oil foods and margarine because it merely indicated that the product contains less than the usual amount of some element as with so many other products (in yet another case, both LIGHT and LITE were found generic for beer).

There are therefore two categories of general information. The first pertains to things slightly more removed from the qualities or characteristics of the goods or services, like instructions. The other relates to merely descriptive terms incapable of attaining secondary meaning.

Common Phrases or Messages

Common phrases or messages are interesting, because there are a large number of examples of people and companies seeking to improperly claim a monopoly over them through misuse of trademark law. The following are just a few examples common phrases and messages that failed to function as trademarks:

- I ♥ DC for use on apparel and souvenirs

- I LOVE YOU for bracelets

- EVERBODY VS RACISM for tote bags; t-shirts, hoodies as clothing, tops as clothing, bottoms as clothing, and head wear; and promoting public interest and awareness of the need for racial reconciliation and encouraging people to know their neighbor and then affect change in their own sphere of influence

- WHITE LIVES MATTER for jogging suits; shirts; sweatpants; sweatshirts; tee-shirts

- NO MORE RINOS! (meaning “No More Republicans In Name Only”) for a variety of paper items, shirts, and novelty buttons

- PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA for electric shavers

- INVESTING IN AMERICAN JOBS for retail store services or promoting public awareness of goods made or assembled by American workers

- FARM TO TABLE for wine

- WHY PAY MORE! for supermarket services

- LEGAL LANDMINES for business coaching services and education services in the field of business

- 40-0 for T-shirts and other sports-related apparel

- AOP (an acronym for “appellation d’origine protégée,” which translates from French as “protected designation of origin”) for wine (note: this was not an application for a certification mark)

Although not (yet) the subject of a definitive court ruling, the sports-related message “threepeat” is currently the subject of at least one trademark registration for clothing. But that registration is highly dubious as being directed a widely-used message related to three-in-a-row sports championship victories. There are actually many examples of questionable assertions of trademark rights related to sports, politics, and other things that have not yet seen definitive court rulings, such as LET’S GET READY TO RUMBLE, MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN, and TRUMP TOO SMALL. And both TACO TUESDAY and TACO TUESDAY were voluntarily surrendered without final court rulings.

Aesthetic Ornamentation

Although not specifically called out as a separate category by the USPTO, some alleged trademarks may also have purely aesthetic ornamental value that fails to function as a trademark. This is to say marks without any words may not convey “information” or a “common phrase or message” but still be ornamental. This most often arises with things like clothing designs and alleged trade dress rights, and to some extent overlaps with the concept of aesthetic functionality. But this can include dubious alleged trademark rights in the color red on shoes (reversed on appeal) and three stripes on clothing, for example.

Potential Exceptions

If something acquires distinctiveness through secondary meaning, an otherwise unprotectable mark can become protectable under trademark law. This possibility first arose with the expansion of trademark law in the mid-Twentieth Century (but such things were not widely considered protectable before then).

There is also a controversial possible exception to failure to function problems for so-called “affinity” marks or “secondary source” usage. The U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) currently accepts evidence of these things to potentially overcome failure to function refusals. However, this USPTO policy is not supported by any significant court decisions. Indeed, in a case challenging the legal foundation of that policy, a judge commented that even though a multibillion-dollar industry has grown up around these practices, “that a house is large is of little matter if it’s been built on sand.”

The weirdest exception is for the olympics. There is a separate U.S. law (35 U.S.C. § 220506) that gives the olympic committee exclusive rights broader than normal trademark law in the emblem consisting of five (5) interlocking rings and the words “Olympic”, “Olympiad”, “Citius Altius Fortius”, “Paralympic”, “Paralympiad”, “Pan-American”, “Parapan American”, “America Espirito Sport Fraternite”, or any combination of those words. This law was challenged but upheld by a divided Supreme Court, with the dissent pointing out how this law eliminates defenses from regular trademark law that are significant to the constitutionality of federal trademark law. While normally trademark law does not provide rights in gross, that is not the case for the olympics.

How to Overcome a Failure-to-Function Refusal

Overcoming a failure-to-function refusal of a trademark application often requires providing evidence of consumer perception that the applied-for mark actually does function as a trademark, or establishing secondary meaning. Of course, these will only be realistic possibilities if the mark actually does function as a trademark. While occasionally it might be possible to respond to a refusal with mere argument, without submitting evidence, most of the time arguments will require corroborating evidence to be successful. Such evidence might be a substitute specimen of use or evidence of the impression the matter makes on the relevant public (such as survey results, internet evidence, etc.).

In the broader sense, having trademark rights in something requires actually using the mark as a trademark. This means making efforts to engage in proper usage and avoid improper use. If that is done, then it should be possible to gather evidence to support an argument that there is trademark usage involved. But it will not be possible to generate evidence of trademark use when something does not function as a trademark and is not or would not be considered a trademark by consumers. For example, mere use of the “TM” or “SM” symbol cannot transform an unregistrable designation into a registrable mark. And, importantly, evidence of function as a trademark must outweigh evidence of widespread non-trademark usage.

Another approach is to amend an application to add limitations regarding the relevant consumers, or delete certain goods/services. If the identification of goods/services is limited to only particular consumers, then the perception of those specific consumers needs to be considered. The perception of other consumers might be irrelevant. This might exclude or diminish the weight of unfavorable evidence of a failure to function.

Limits

When alleged trademark rights are asserted against another party, there may be defenses that arise related to a failure of the asserted designation to function as a trademark, or simply other defenses that protect the ability to make use of that designation under certain circumstances.

Descriptive or nominative fair use can apply to permit usage by others, even when there might be secondary meaning. Fair use is a limit on trademark rights even when there is a registration, and even when that registration is incontestable (see 15 U.S.C. §§ 1115(b)(4); see also § 1125(c)(3)(A)). This is a potential defense against the assertion of a dubious trademark registration that does not appear to function as a trademark, or against infringement allegations that relate to non-trademark usage by another party.

Genericness might also be a defense and a ground for cancellation of a registration. For instance, there are cases where courts have held that even adjectives can be generic, like the LITE beer case cited above. Or, in another case, BRICK OVEN was found to be generic for frozen pizzas. In these situations, a distinction is sometimes made between terms that were widely used before adoption and those that were coined but later became generic. But this does not make allegedly coined terms invulnerable to genericness—or preclude questioning as to whether they were truly coined/fanciful terms to begin with.

In district court litigation or TTAB proceedings, other defenses or challenges to an asserted registration or unregistered mark might also be available, like abandonment, unclean hands (or other equitable doctrines), etc. However, most cases involving failure to function are treated as evidentiary ones involving the sufficiency of specimens of use and there have not yet been definitive court rulings on failure to function arguments and defenses after a registration has been granted.

Other Related Concepts

In general, unless a patent or copyright protects an item, it will be subject to copying. Trademark law cannot be used to exclude competitors from the market. Accordingly, for alleged trade dress rights in product configuration, there is never inherent distinctiveness, and secondary meaning and acquired distinctiveness must be established. But there may be situations in which secondary meaning can never be acquired because the product configuration is incapable of functioning as a trademark to identify source. So, although these other limits are often discussed in public policy terms, they can also been seen as concern about failure to function.

In one case, involving the assertion of (unregistered) trademark false designation of origin rights in a documentary television series for which copyright had expired, the television series materials could be copied without liability. This was a clear case of improperly attempting to use trademark law to undermine fundamental aspects of copyright law. However, the court did not address how secondary meaning might arise, if at all, in this situation.

The U.S. trademark laws also explicitly prohibit trademark rights in things that are functional rather than source identifying. That places purely functional aspects of products outside the scope of trademark law. For example, in one case the configuration of partly chocolate-covered cookie sticks was found to be purely functional and unprotectable under trademark law as trade dress.

But this gets more difficult to evaluate when dealing with something aesthetic like copyrightable material, including aspects of entertainment performances that the public would see as the service/thing itself. For instance, one court has said in a different case that trademark law does not protect the content of a creative work of artistic expression as a trademark for itself. The court declined to accept an argument that was tantamount to saying that a product itself—in that case, a song—can serve as its own trademark. The different, source-identifying function of trademarks requires that a trademark in a musical composition not be coextensive with the (copyrightable) music itself. The court’s reasoning very much reflects failure-to-function concerns. Although, curiously, the court noted the defendant’s concession that the song title had acquired secondary meaning, a position that is rejected by the USPTO for single-work titles, due to a failure to function.

So-called aesthetic functionality limits trademark rights. However, that limit has, at times, been set out somewhat circularly as depending on whether the recognition of trademark rights would significantly hinder competition. But these assertions of trade dress or other trademark rights in things/works themselves are usually attempts to hinder competition rather than protect consumers from deception. This has led to rather arbitrary and subjective court decisions in this area, with variable and inconsistent outcomes.

Conclusion

From the examples given above, refusals for failure to function are an important check against overreaching and misuse of trademark law. Many of these examples relate to clothing and merchandising, in which an entity tries to improperly use trademark law to obtain a monopoly over widely used sentiments and slogans/taglines.

Failure to function issues tend to involve so-called “propertization” of trademarks. This moves away from the basis of trademarks in consumer protection. Instead, a failure to function is most typical when someone is trying to appropriate and “monetize” some existing sentiment for their own private benefit or trying to unfairly suppress competition.

In the hilarious TV series “The Office” (American version), there is an episode (season 7, episode 14) where small business entrepreneurs show up for a seminar organized by a paper salesman. One of the attendees explains his business idea as getting point-two cents from every phone call or online shipping order (without providing any benefit, simply taking a cut). One of the show’s regular characters tries not to grimace when hearing this ridiculous idea for a grift. But that scene encapsulates the way numerous entities have analogously tried to use trademark law as a “get rich quick” scheme to monopolize common slogans and general information for their own benefit.

The best approach when branding products and services is to select a strong, distinctive mark in the first place, then consistently use that mark properly. When those things are done, failure-to-function refusals simply will not be an issue.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.