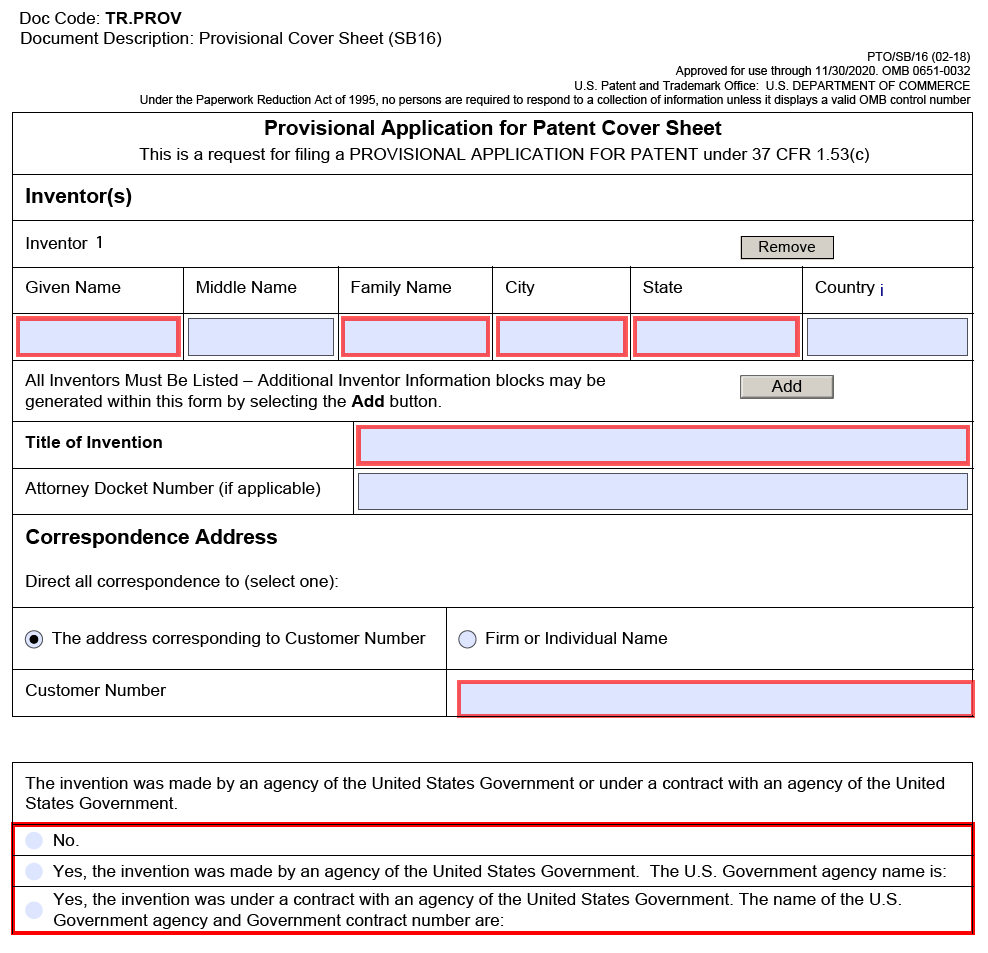

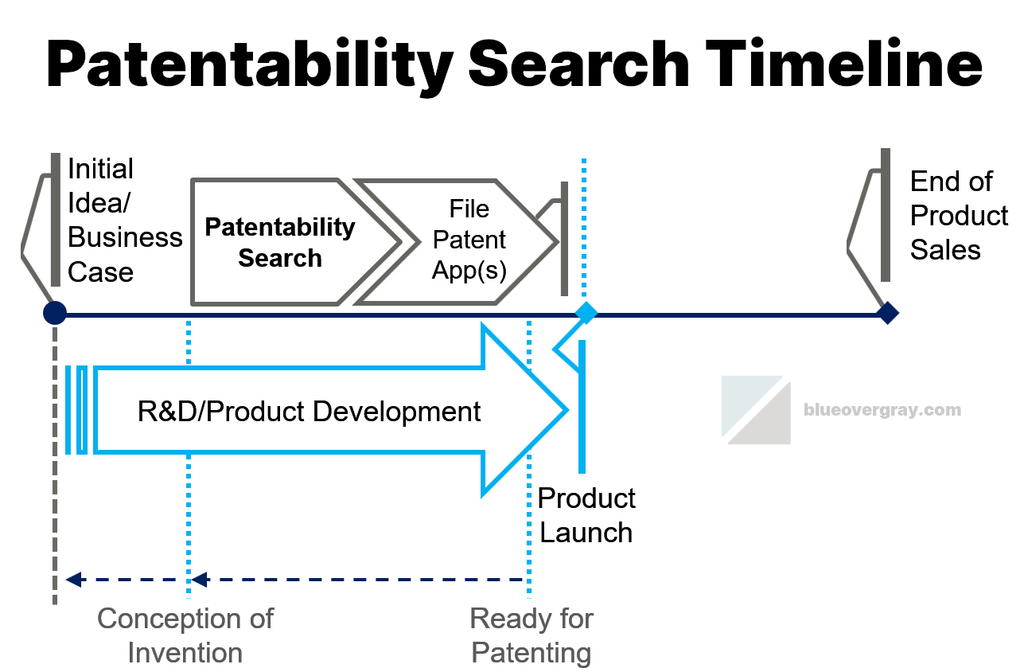

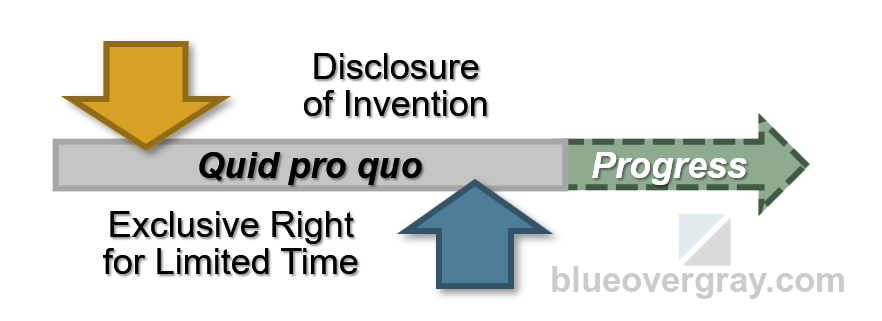

A provisional patent application — sometimes called a “provisional application”, “provisional” or “PPA” for short — is a type of patent application that can be filed in the United States. They were intended to provide lower-cost first patent filings for new inventions. A provisional acts kind of like a placeholder for up to one year. It is never substantively examined for patentability. And a provisional can never directly be granted as an enforceable patent. But you can file a further non-provisional application that claims “priority” back to the provisional application filing date. A provisional filing lets you put a stake in the ground to preserve patent rights, so-to-speak.

The question at hand is really what factors weigh in favor or against filing a provisional. In short, what are the pros and cons of filing a provisional?

Advantages and Benefits

Some of the most common advantages and benefits of a provisional patent application are the following:

- Extends patent expiration date (patent term benefit)

- Allows products to be marked “patent pending”

- Establishes filing date (priority) to cut-off potential later-arising “prior art”

- Allows commercial potential of invention to be explored for up to a year without losing patent rights

- Helps win race to the patent office if others are working on similar inventions

- No need to comply with formalities for drawings, etc.

- Might be filed quickly in the face of an impending loss of patent rights associated with a public disclosure/use or sales activity

- Kept confidential (at least until cited in a later-published application or granted patent, such as through a priority claim)

- Evidence of inventorship as of filing date

- Lower initial official filing fees than a non-provisional application

- Can later claim priority to multiple provisional applications

One of the biggest benefits of a U.S. provisional application is that the time period between the provisional filing date and the filing date of a non-provisional application claiming priority back to the provisional is not counted against patent term. This means that a provisional can push out the patent expiration date by up to a year (but this happens partly by delaying the grant of any patent by roughly the same amount of time). It can effectively extend the patent term to 21 years from filing. For some inventions, the most valuable period of patent protection may be later in the term, making such an extension valuable.

A pending provisional application also allows products to be marked as “patent pending.” That serves as a warning to potential copyists. It may also provide marketing and business development benefits.

Filing a provisional application establishes an official “filing date” for the disclosed invention. This is significant because patent rights generally go to the first inventor to file a patent application. So provisionals help win the race to the patent office. If there is some public disclosure that occurs after the provisional filing date it will not count as “prior art” against a later claim with “priority” to the provisional filing date. Prior art can potentially bar patentability. It can stem from your own disclosures and activities or someone else’s. Either way, a provisional can potentially exclude later-arising disclosures from being used as prior art against you. It is this aspect that allows you to disclose the invention to potential customers, etc. during the year after the provisional filing without loss of rights.

Another advantage is that provisionals do not require formal drawings, claims, etc. Here we can loosely distinguish between “informal” and “formal”/”full” provisionals. A “formal” or “full” provisional is one that could be filed as a non-provisional because it is written up in full detail to comply with all the requirements of a regular non-provisional utility patent application. An “informal” provisional is one that would not be sufficient or compliant as a non-provisional utility patent application.

A formal/full provisional generally offers no savings on preparation costs and effort compared to a non-provisional application. But the official filing fee is less and an eventual patent expiration date can be extended. The main advantage is that you reduce the risks of having inadequate disclosure of the invention. Not all provisional applications are equal. A provisional is really only as good as the disclosure it contains. If a provisional application omit details that are essential to patentability of an invention the provisional may be ineffective or even worthless. Putting in the effort to prepare a full disclosure of the invention reduces such risk.

An informal provisional departs from the format of non-provisional applications and granted patents somehow. It might have drawings with shading or lacking reference characters (labels), pages pulled from presentation slides with text in different orientations, figures (graphical illustrations, diagrammatic views, flowcharts, and/or diagrams) inserted into the middle of pages of descriptive text, etc. They sometimes repurpose existing documentation. Such informality may allow for quick filing. For example, if disclosure of the invention at a trade show or customer meeting is immanent, an informal provisional can be filed on an urgent basis to preserve patent rights.

Any type of provisional allows exploration of the commercial possibilities of the disclosed invention before deciding if a non-provisional application is worthwhile. The USPTO keeps provisional applications secret initially. If you abandon the provisional without claiming priority to it or disclosing it in some other way, its contents will never be made public by the USPTO. That means you might be able to still pursue patent protection later (despite loss of priority) if there was no intervening public disclosure or commercialization of the invention by you or anyone else. But if you claim priority to a provisional in a non-provisional application the contents are made public (upon publication or grant).

When seeking to generate interest in an invention or make sales, do keep in mind the scope of protection a provisional will and will not offer. A provisional is generally effective if it includes as much or more disclosure as what is publicly disclosed, publicly used, sold, or offered for sale (or what has already been publicly disclosed, publicly used, sold, or offered for sale within the prior year). The limits of protection are discussed in the disadvantages and risks section below.

Provisionals are also occasionally useful in providing evidence of inventorship. For instance, a provisional might provide some evidence of independent invention as of the provisional filing date (as part of self-authenticating official U.S. government records), although this is not always sufficient by itself.

Additionally, if research and development is ongoing, it is possible to file multiple provisional applications. A later non-provisional application can claim priority to any or all of those provisionals — assuming they are all filed within a year and have at least one common inventor. And one (or more) of those provisionals could be abandoned and kept confidential if unnecessary to later patenting strategies. In other words, with up to a year of hindsight, you could pick and chose some but not all of the provisionals for priority claims. And new matter can still be added to a later non-provisional application too. That new matter just won’t receive priority to an earlier provisional filing date.

Disadvantages and Risks

Some of disadvantages and risks associated with filing a provisional patent application are the following:

- Adds to total cost of obtaining a patent

- Delays the (potential) grant of a patent

- Risk of inadequate disclosure in an “informal” provisional

- If foreign patent protection is eventually sought, the disclosure requirements may differ from U.S. law

- Patentability might already be barred before filing (that is, the provisional is already too late)

- Not available for designs

- Foreign law may necessitate first filing in a foreign country or obtaining a foreign filing license before filing the provisional for inventions made wholly or partly outside the United States

Filing a provisional adds to the total cost of obtaining a patent. If you simply file a non-provisional application from the start you avoid the provisional filing fees entirely, plus any attorney fees associated with the provisional.

A provisional also delays the grant of a patent (assuming the invention is patentable). Though, in exchange, the expiration date of the patent is pushed out the same amount of time. Sometimes that trade-off is acceptable. But if the invention is likely to be copied, delays in obtaining a patent might delay enforcement action against infringers.

The main risk of a provisional filing stems from it containing an inadequate disclosure. From one perspective, filing a patent application (provisional or non-provisional) is better than not filing when it comes to helping protect an invention. But not all provisional applications are equal. put another way, the question is not merely about filing or not filing a provisional but about filing an adequate and sufficient provisional or not. A poorly-prepared provisional application may inadequately or unfavorably disclose the invention. In that sense, it may create a false sense of security. Never forget that a provisional is only as good as the disclosure it contains. Whether a given provisional is good enough comes down to what public disclosure and commercialization takes place, the scope of the prior art, and your overall patenting strategy and expectations.

If you file a provisional application to avoid a patentability analysis or even just to avoid hard thought about what is really the invention and how to claim it, you can’t know if the provisional application contains sufficient disclosure of a patentable invention. This might be risky if you rely on an “informal” provisional that cuts corners compared to a “full” or “formal” provisional (see definitions above). That is a particular concern if you sell or publicly use a product but important technical details about that product were omitted from the provisional.

Legally, the provisional application disclosure (written description) must enable one of ordinary skill in the art to practice the entire invention claimed in a later non-provisional application. There have been many cases where omission of some detail in a provisional application (that turns out to be important to patentability of a later-filed claim) resulted in a loss of priority to the provisional filing date for one or more claims. So you have to understand what will be later claimed in order to know if a provisional’s disclosure is sufficient. Complex or highly abstract technologies raise this issue. For example, an invention related to signal processing is probably not directly observable, meaning a provisional write-up must sufficiently capture the unobservable.

An important legal concern is that you cannot preempt a future invention before it has arrived. So you need a disclosure in the provisional that corroborates conception of the invention you will later claim. If you later try to claim an entire “genus”, this often turns into a question of whether the provisional disclosure was limited to a particular “species” (i.e., specific embodiment) within that genus or made clear that an entire genus was invented and enabled — usually by disclosing either a representative number of species in that genus or structural features common to the genus sufficient for member species to be recognized. Another potential issue involves claiming ranges of particular values. If you later claim a narrow numerical range, perhaps to avoid prior art falling in a different range, previously disclosing only a broader range might not be sufficient. These are fact-intensive inquiries.

Legal requirements in other countries vary. For instance, other countries may have stricter requirements about claims using nearly the identical language as the preceding description of the invention. And other countries may not permit reliance on disclosures contained only in drawings. They may instead look for textual descriptions of what is in a drawing. If foreign patent protection is (or might be) contemplated, differences in disclosure requirements should also be considered when preparing the provisional.

A provisional application also won’t save you when patentability is already barred. For instance, if the invention was already sold or publicly disclosed by the inventor more than a year before, then patentability is already barred in the United States. Any pre-filing public disclosure by the inventor may bar patenting in some other countries too. And an invention that lacks utility, is anticipated, or is obvious won’t be patentable either, regardless of whether a provisional was filed.

Additionally, provisional applications cannot be used in connection with designs. If your invention pertains to an ornamental design of a useful article, a regular (non-provisional) design patent application is the only option.

Lastly, some countries have laws that require patent applications to be filed in that country first if the invention was made or conceived in that country, or that a license be obtained to file abroad first. If any inventor resides in a foreign country or performed inventive activity while temporarily outside the United States, any applicable foreign laws should be considered. Those laws may impose penalties for making a provisional filing in the United States rather than in the foreign country. Foreign priority cannot be claimed in a U.S. provisional application.

Concluding Thoughts

Provisional patent applications are routinely used by applicants ranging from individual inventors to large corporations. There are many excellent reasons to file a provisional, including extending the expiration date of any resultant patent. It is always worthwhile to consider filing a provisional application. But a hastily- or poorly-prepared provisional may be insufficient to preserve a priority claim. Cutting corners to file a provisional cheaply or quickly imposes some limits on the scope of protection obtained. Always remember that a provisional is only as good as the disclosure it contains — that point is worth repeating.

A common mistake in applications self-prepared by inventors is to focus on the prior art or problem to be solved but omit the crucial disclosure of the substance and structure of the new invention — or do so only with general, vague, and conclusory statements that fail to establish anything more than a hope that an invention will be discovered later. A provisional also won’t be effective if key enabling aspects of the invention are purposefully withheld from the application. For instance, a disclosed algorithm cannot obscure key steps of the purported invention within a “black box”. Another common mistake is to characterize the invention in a way that limits the ability to claim the invention more broadly (or narrowly) later on.

Whether a provisional patent application is worthwhile will ultimately depend on circumstances such as the subject matter of the invention(s), the state of the art, any looming bars to patentability, the business goals and objectives of the applicant, the realistic commercial value of the invention, and the applicant’s worldwide patent strategy.

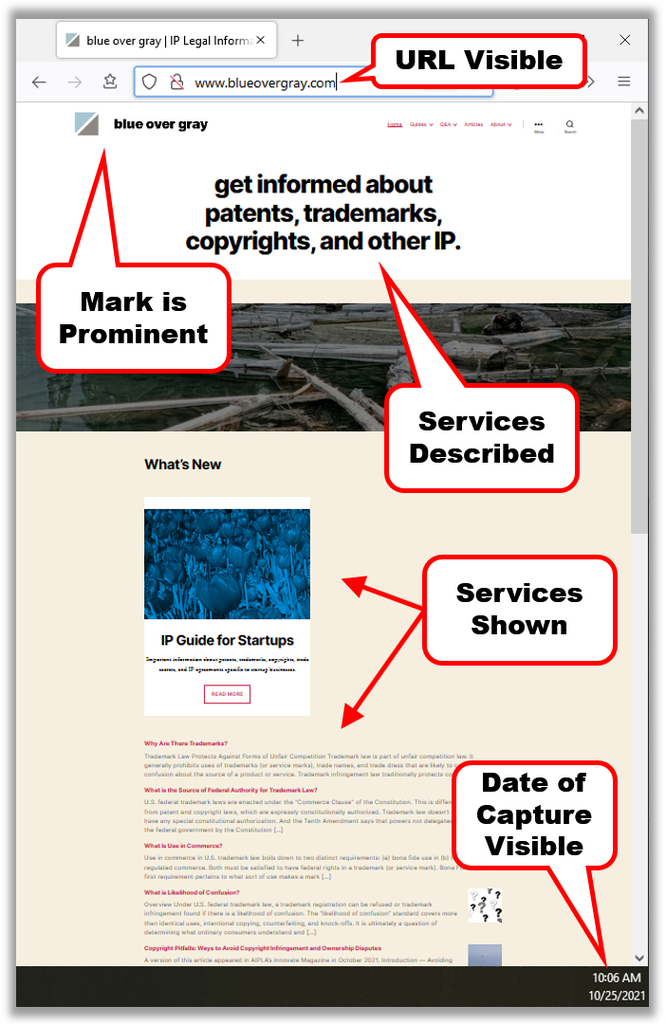

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.