It is beneficial to have advertising undergo legal review prior to release. Such review should generally cover a number of different concerns, including false advertising, trademark infringement, right of publicity/privacy, copyright infringement, special considerations for regulated industries (i.e., industry-specific laws and regulations requiring certain disclosures, etc.), medium-specific requirements (for commercial email, phone marketing, TV/radio broadcasting, etc.), and more. The following addresses legal treatment in the USA. Laws may differ in other countries. Legal review of particular advertisements should be directed to a knowledgeable attorney in the relevant jurisdiction(s).

Establish Advertising Review Procedures

In general, have a procedure for advertising review before that advertising is released. Be clear about how such protocols apply to business-related social media or other online accounts, which are usually just another form of advertising. Also be clear how these procedures apply to vendors, consultants, and spokespersons operating on your behalf. You very well may be responsible and liable for their actions, and you should not assume they will automatically comply with the law or your own requirements. Periodically check to see that these protocols are actually being followed.

Make sure that appropriate documentation is created and maintained. For instance, require sufficient record-keeping to preserve any licenses, authorizations, releases, objective evidence supporting ad claims, and the like. Retain those records for a sufficient time and in a place where they can be located (by others) if and when needed. Online advertisements may be active for many years, and various portions of ads might be reused for later ones, so such records should ideally be kept as least as long as as the advertising material is in use.

The scope and thoroughness of advertising reviews should take into account the prominence and scope of the advertising. Major mass media ad campaigns deserve extra attention. Also, anything that “feels” questionable, or seems to push boundaries of legal or ethical acceptability, should also receive appropriate review. Lastly, focus should be drawn to things that are most material to prospective consumers.

Many laws regulating advertising exist because businesses often have incentives to be less than truthful or accurate. The point of marketing is to create demand, which can easily turn into a matter of lying or dubiously creating meaning out of nothing. Moreover, marketing and sales people, as individual employees or vendors, may feel pressured to put out legally prohibited or at least questionable content to satisfy management or others. People may also argue for a race to the bottom, pointing to questionable if not clearly illegal conduct by others as justification for doing the same—or worse. On top of that, some illegal advertisements go unpunished simply due to lack of resources by enforcement agencies and there may be arguments to try to get away with something on that basis. Advertising reviews should allow an opportunity to put a halt to efforts that run afoul of the law or that simply put a business in an undesired light (even if legal).

Trademarks

Trademarks should be legally cleared as part of initial selection. That is, make sure you select a mark that will not create a likelihood of confusion with one already in use by another entity. Trademark infringement can arise even if the marks are not identical and even if the goods and services are not the same. This is the best way to avoid infringement allegations. Of course, this is less about use of a mark in a specific advertisement than about overall branding strategies.

Another issue to consider in any given ad is proper usage of your own trademark(s). This is about maintaining rights in your own mark(s). Use your mark(s) consistently, as a source-identifying trademark (as an adjective rather than a noun or verb), and use appropriate symbols (®, ™, SM) or comparable trademark identifications (like “Reg. U.S. Pat. & Tm. Off.”). Even if marketing folks think it is appealing to misuse trademarks in an ad, doing so can damage trademark rights or even result in loss of trademark rights—sometimes called genericide.

The next issue to consider is any usage of someone else’s trademark(s). While comparative advertising is permissible, and nominative or descriptive fair use may apply, intentionally using someone else’s trademark or something confusingly similar to someone else’s mark should receive extra scrutiny. Use of comparative advertising has marketing benefits but also tends to heighten the risk of a legal dispute under trademark and/or advertising law.

To help reduce risks associated with comparative advertising, you should at a minimum make sure statements are not false or misleading (including both express statements and any implied meanings even if not the only possible interpretation), material information is not omitted, comparisons are fair (and not “apples to oranges”), and material support for claims is documented before making them. Consider also the context, and avoid anything that makes a competitor’s trademark more prominent than your own or that otherwise may confuse consumers about the source of the goods or services.

Also think about what you would think if the situation was reversed. That is, what if your competitor was using your trademark in the way you plan to use your competitor’s mark? Would you have concerns?

“Dilution” is another area of law that gives special additional rights to famous brands. Tarnishing or blurring the rights of a famous brand can give rise to liability. Advertising that looks like it rides on or nips at the coattails of a famous brand could give rise to dilution issues, potentially, even if it would not raise trademark concerns for an ordinary, non-famous brand.

False Advertising and Truth in Advertising

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has national authority to prevent unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting interstate and foreign commerce. Federal trademark law also allows private businesses to sue on certain false advertising claims. Additionally, states have various advertising, unfair competition, and deceptive trade practices laws. Most of these laws are somewhat open-ended. But, in general, they can apply to advertising and generally require that ads not be unfair or deceptive/misleading.

The standards for truthful advertising can be a little fuzzy. These matters are prone to judgment calls. But some of the most basic considerations and requirements are as follows (see also FAQs from the FTC).

Advertising claims must be substantiated by evidence in advance. It is not sufficient to make a statement based on a hunch that you can (try to) justify it later if needed. This is because advertisers imply that there is a reasonable basis for such a claim. Even statements in ads that later turn out to be true are legally prohibited if there is not a “reasonable basis” for the claims, meaning there is objective evidence that supports the claim. Tests or studies used to support advertising claims must be conducted using methods that experts in the field accept as accurate. They also must be commensurate with the advertising claims actually being made.

Mere “puffery” that reflects a purely subjective claim that consumers would not take seriously/literally is generally permissible without substantiation. For instance, a claim to offering “the best cup of coffee in the world” or that “our widgets are excellent” is often acceptable because consumers will recognize it as a purely subjective statement of opinion. But a claim with an objective (factual) component like “rated the best by most doctors” or “more consumers prefer our widgets to any other” or “our widgets last longer than the most popular brands” would not be seen as mere puffery by consumers. These latter types of objective advertising claims must be both true and substantiated. Context can also matter in these distinctions.

The FTC especially scrutinizes health & fitness and safety claims, for instance, and advertising directed at children (especially those under age 13) is also regulated more. Claims and implications that products are made in the USA, and “green” or environmental-friendliness claims also tend to be areas of frequent concern. Competitors may also take issue with false or misleading comparative advertising claims, which are discussed above with respect to trademarks. Certain types of claims may also implicate other agencies or laws, such as the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), which has other requirements for certain drugs and cosmetics and associated advertising.

Warranties and guarantees are subject to special legal requirements. Some of these pertain to how they are advertised. Others pertain to disclosure requirements for stating the terms and conditions as well as making those available pre-sale.

Endorsements and testimonials, including those by “influencers”, can raise many questions about whether their use is truthful and not misleading. The FTC provides an endorsement guide that is worth consulting. Some common concerns involve failing to disclose that someone is a paid endorser/influencer or misleading consumers about an endorser’s use or familiarity with the product or service in question (or lack thereof).

Copyrights

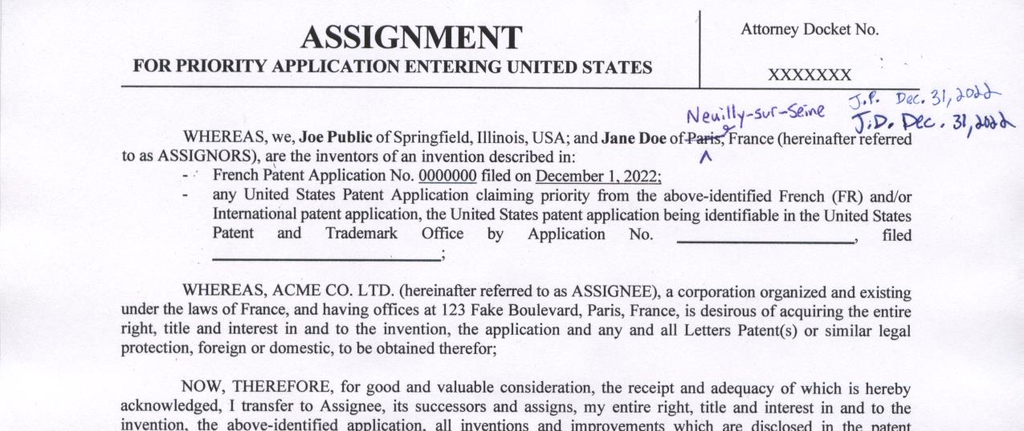

Copyright clearance is an important part of advertising review. Materials used in ads like photos, graphics, text, etc. that are not completely original creations require permission to be used. Unauthorized use may constitute copyright infringement. Copyright clearance should involve obtaining and documenting—in writing—authorization for use of any copyrighted materials that are used, including legally reasonable verification that the materials are uncopyrighted or have fallen into the public domain.

There are many nuances about who owns copyright and what is permissible to do with someone else’s copyrighted work. When vendors or consultants are involved, and they often are when it comes to ad copy, you do not automatically own the copyright just because you paid for it. There can be implied licenses. But new, unexpected, or gradually expanded use might exceed an implied license. Also, there are many myths about what is legally permitted. For instance, there is no bright-line legal rule that says changing 10% of a copyrighted work or four things in a work—or some other percentage or number—avoids infringement liability.

When you get a license, make sure the scope covers your intended use. It is fairly easy to slip up and get the wrong license, or misunderstand the scope of the license you paid for. Also, consider getting an indemnity from the party licensing materials to you.

Fair use may apply, sometimes. But that is a context-specific, multi-factor analysis without any bright lines. And in the advertising context, the commercial nature of the use is a factor explicitly counted against a finding of fair use by statute. It is true that parody and criticism can occur even in a commercial advertisement as a fair use. Yet such things may only support fair use if they parody or criticize the particular work in question as opposed to merely using it without authorization to parody or criticize something else. There is a tendency for claims of “fair use” to be overused and unjustified in the context of commercial advertisements. Many times, you simply need authorization, such as a paid license.

And, no, just because something was available on the Internet does not mean that is can be freely used in an advertisement.

Rights of Publicity and Privacy

The rights of publicity/privacy are potentially implicated any time advertising materials contain a person’s name or likeness without their consent or authorization. These issues most often arise in the context of the unauthorized commercial use of photos or videos that depict famous people or celebrities or that thrust a private person into the public spotlight.

Review of advertising should include verification that their is an appropriate release from any persons whose name or likeness is used. A release of this sort is sometimes called a “model release”. Although in other industries this might go by other names or be included within another agreement, such as a “materials release” in film or TV productions.

Bear in mind, however, that having a copyright license to a photo, video, or the like is not enough, alone, to clear any right of publicity/privacy issues. These releases and copyright licenses often need to come from different people. For instance, a copyright license or assignment for a photograph would often come from the photographer while the publicity/privacy release would come from the person(s) appearing in that photograph (or a parent/guardian).

Some states have laws limited rights of publicity for deceased people. There can also be exceptions for references to public figures, although those exceptions probably will not apply to commercial advertisements that give the impression of an endorsement or approval.

If obtaining stock images, consult the terms of a license to see if a model release is included. If not, use of the stock photo may still give rise to issues. For example, sometimes a minor celebrity’s likeness might appear in a stock photo unintentionally. Or, as another example, if your intended use would tend to portray the person depicted in a false light, such as implying that the person has a disease, committed wrongdoing, or would embarrass them, there may be a claim for invasion of privacy or a similar “false light” claim.

Disclaimers

A disclaimer may be helpful but is not a “get-out-of-jail-free” card. Use of a disclaimer will not undo otherwise false, misleading, or confusing ad content. That is to say a disclaimer is only helpful to the extent it is actually effective on the viewing audience. This is something you can generally only speculate about in advance. Accordingly, while a disclaimer may be worthwhile, it may be a helpful exercise to ignore any such disclaimer as part of an initial legal review and consider the other content of the advertisement as if the declaimer was not present at all.

Email Advertisements and Anti-SPAM Law

The CAN-SPAM Act governs commercial advertising emails. Those are emails whose primary purpose is commercial. Emails whose primary purpose is to provide transactional or relationship content (which facilitates an already agreed-upon transaction or updates a customer about an ongoing transaction) or other content (which is neither commercial nor transactional or relationship, such as political campaign information) is not covered by the federal CAN-SPAM laws. States also have various email marketing laws but those are mostly preempted by federal law and therefore inapplicable to commercial emails (except for fraud and deception issues).

General requirements for compliant email advertising, as explained in an FTC guide, include:

- Accurately identify the person or business who initiated the message and do not use false header information

- Don’t use deceptive subject lines

- Clearly and conspicuously disclose that your message is an advertisement (not required if the recipient has previously expressly opted-in to such emails)

- Include your valid physical postal address

- Include a clear and conspicuous explanation of how the recipient can unsubscribe (opt out) from future messages, such as a reasonably prominent, working “unsubscribe” link

- Honor unsubscribe (opt out) requests promptly

- Make sure vendors and employees are following the law

Some additional guidance is available in the FTC’s “Candid answers to CAN-SPAM questions.”

One area that can give rise to issues involves use of purchased email lists. Despite the fact that vendors sell them does not mean that it is legal for you to use them in any and every possible way for mass email marketing purposes. It still matters how you send email messages and the specific content of those messages. For instance, use of a purchased list should not override a prior opt-out request. But, on the other hand, use of purchased email lists is not expressly prohibited under CAN-SPAM and prior consent (that is, an opt-in) is not required, so long as the sender (initiator) of the message clearly and conspicuously identifies a commercial email as an advertisement.

In practical terms, mass email service providers may have their own policies that are more restrictive that any applicable laws. Such providers are sensitive to spam reports and may take action to block you or terminate your account if too many complaints are received. That could happen even if complaints fail to allege anything illegal or are baseless (such as a spam report by someone who expressly opted in). For instance, some providers prohibit the use of their services or platform to send emails to purchased email lists—even if laws do not specifically prohibit doing so.

Phone and Broadcast Advertisements

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has authority over phone and TV/radio broadcasts. There are additional rules and regulations that apply to advertisements and commercial messages in those formats. For instance, randomly dialed robocalls are generally prohibited. In addition, the FTC maintains a “do not call” registry for telemarketing that must be honored.

Consumer Privacy and Handicap Accessibility

There is also a growing body of laws regulating collection and retention of consumer data, particularly at the state level (e.g., California’s CCPA) and in foreign countries—like GDPR in Europe and PIPEDA in Canada. But some federal laws may apply too. These laws can be implicated by online advertising, for instance. Collection and use of personally identifying consumer information should be scrutinized. In some cases, even laws involving biometric information privacy could be implicated. The sale, purchase, and/or exchange of consumer personal information to or from brokers, business partners, or other third parties and the collection of online ad or web page tracking data are of particular significance here.

Additionally, consider whether online advertisements implicate laws requiring accessibility for persons with disabilities. These can arise from state or federal law, potentially. General online accessibility standards and best practices are useful here, and might be worthwhile to implement even if not strictly required by law for certain commercial advertisements. Bear in mind, however, that “accessibility” is something of a moving target and is not defined by bright lines.

When working with vendors and contractors, be aware that they may try to push compliance burdens onto you via contractual terms. This might even extend to situations where vendors are selling services or tools that cannot conceivably be used in a legally compliant manner, or at least not in ways with any practical value to the advertiser.

Have an invention you would like to patent? Have a brand you would like to register as a trademark? Concerned about infringing someone else’s intellectual property? Is someone else infringing your IP? Need representation in an IP dispute? Austen is a patent attorney / trademark attorney who can help. These and other IP issues are his area of expertise. Contact Austen today to discuss.

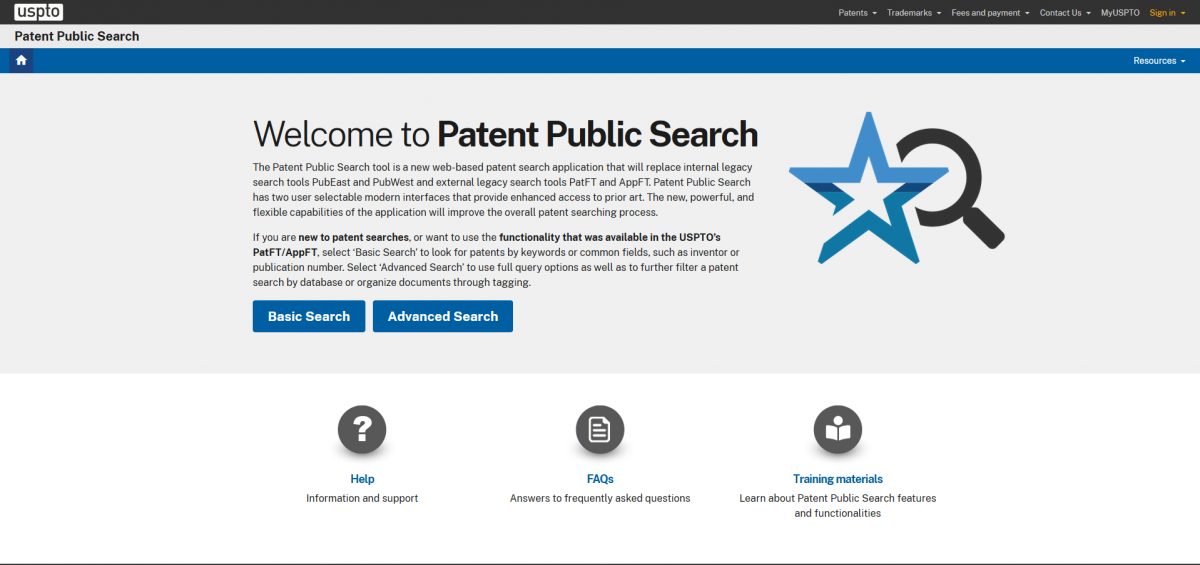

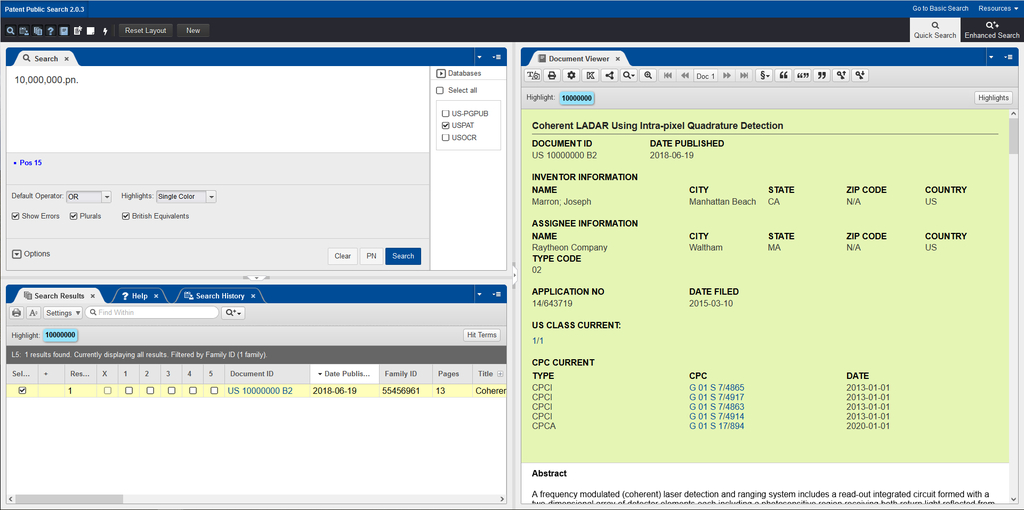

![Annotated screenshot of Patent Public Search Advanced Search Interface "Document Viewer" “T / [camera icon]” button to toggle between text and PDF image views](http://www.blueovergray.com/wp-content/uploads/text-PDF-toggle-button.jpg)